Why research competency is fundamental to development and improvement

As a vocal advocate for the use of evidence in policy and practice, the social scientist Philip Davies stated almost 25 years ago[1] that educational professionals at all levels should be able to engage in four key tasks:

- pose answerable questions;

- search for relevant information;

- read and critically appraise evidence; and

- use the resulting conclusions for educational decision-making.

These key tasks correspond to the stages of research engagement when depicted as a complex, cognitive, knowledge-based problem-solving cycle. It’s not surprising, then, that similar processes can be found in analogous frameworks relating to approaches to school improvement. For instance, models of data-based decision-making[2] consider teachers’ competent engagement and use of research – that is, of data and evidence – as crucial for quality improvement and professionalisation in educational practice.

Actually, schools have access to an astonishing amount and variety of data and evidence, including their own data (e.g. student feedback, collegial observations), external data (e.g. school inspections, regular mandatory pupil performance assessments, central exams) and even more ‘generic’ scientific research evidence (academic and professional literature). Accordingly, there is some evidence that if educators engage with evidence to make or change decisions, embark on new courses of action or develop new practices, this can have a positive impact on both teaching and learning.[3]

Yet despite this, teachers appear to fall back more readily on intuition which, unfortunately, is prone to bias and mistakes.[4] We also know attempts to develop the capacity of school leaders and practitioners to engage in reflective problem-solving, such as research learning networks or data teams[5], can sometimes fail to facilitate deep research engagement.

It is assumed that a general obstacle in this context is that profound data-based or evidence-informed decision-making processes require educational staff that are proficient in a range of interrelated areas of research competency. These include:

- identifying a problem of practice;

- collaborating with relevant stakeholders;

- collecting, analysing, synthesising and using data to check for misconceptions; and

- considering a variety of contextual and ethical conditions.

Such a level of research competency has been characterised as being a ‘developing expert user‘.[6] To quote the famous American educational psychologist Lee Shulman, this means that educators are sufficiently equipped to choose ‘from among an instructional repertoire which includes modes of teaching, organising, managing and arranging’[7] and to do so – in the context of this article – on the basis of data, evidence or research.

It is all the more surprising, therefore, that little is known about the general level of proficiency in engagement with evidence present amongst teachers and school leaders – and particularly whether such proficiency can be acquired in teacher training programmes. Against this backdrop, we will consider whether it is at all possible to assess the necessary competencies in the context of two different English teacher training programmes.

What is meant by research competency?

The competency to engage with data, evidence, or more generally with research is referred to by various terms, e.g. as ‘Assessment Literacy‘ (the ability to administer, score and understand standardised student assessments)[8], ‘Data Literacy‘ (the ability to make instructional decisions based on various kinds of data feedback)[9] or ‘Statistical Literacy‘ (the ability to read different data representations and understand statistical concepts).[10]

The term ‘Educational Research Literacy‘ can thus be used to explicitly address the engagement with data and evidence from educational research as part of a comprehensive research cycle.[11] We define Educational Research Literacy as ‘the ability to purposefully access, reflect and use evidence from educational research’.[12]

For a long time, research competency was mainly studied through self-assessments, and these continue to dominate the field.[13] However, despite the global policy movement towards accountability, evaluation and assessment in schools[14], only a few standardised assessment procedures have subsequently emerged, and these have proved to be psychometrically weak.[15] To close this research gap, efforts have been made in connection with funding initiatives in Germany to develop valid and feasible standardised tests for the assessment of competencies in higher education (e.g. engagement with research).[16]

We, too, have developed a standardised test which proved psychometrically sound for the assessment of Educational Research Literacy, with its three competency facets being Information Literacy, Statistical Literacy and Evidence-Based Reasoning.[17] Based on that, we have already demonstrated that German in-service teachers are less proficient in engaging with data and evidence than pre-service teachers, but that the required competencies can be supported or made up for in targeted in-service courses.[18]

Such training courses also aim to teach ‘soft’ elements. By this, we mean affective-motivational characteristics that have been shown to have a beneficial learning effect on how competent teachers can engage with data or evidence; for example, the perceived usefulness of evidence from educational research.[19] In contrast, a lack of self-confidence in the ability to engage with evidence or negative feelings about research methods adversely affects the motivation to engage in or with research and thus undermines the further development of research-related competencies.[20]

The situation in English teacher education

In comparison to Germany, the situation in England is perhaps less well-advanced. To begin with, conceptualisation is limited. The British Educational Research Association, for example, defines ‘research literacy’[i] as ‘the extent to which teachers and school and college leaders are familiar with a range of research methods, with the latest research findings and with the implications of this research for their day-to-day practice, and for education policy and practise more broadly. To be research-literate is to ‘get’ research – to understand why it is important and what might be learnt from it, and to maintain a sense of critical appreciation and healthy scepticism throughout‘.[21]

To this can be added the thoughts of Boyd[22], who argues that teachers’ research literacy needs to also include a critical perspective of the big picture, including an understanding of educational research in relation to politics and democracy and critical skills in interpreting professional guidance sources.

The issue is that these definitions are yet to be operationalised (i.e. transformed into research instruments). Understandably, therefore, our comprehension of the extent to which teachers in England are research-literate is limited (with Boyd, for example, acknowledging that further research is required to extend our understanding of teachers’ research literacy). While we know the extent to which teachers report engagement with research, we have only a limited understanding of the extent to which they are proficiently educated to engage with research in an appropriate – that is, systematic – depth.[23]

What research we do have seems to imply, however, that the answer is ‘not much’. Instead, small-scale survey work suggests that teachers feel that ‘research evidence needs to be ‘translated’ and made practitioner-friendly if they are to use it effectively’.[24] We consider initial and in-service teacher training not as separate entities, but as part of a continuous process in line with the idea of lifelong learning.[25] This is why we decided to start this research in more accessible study programmes in the field of initial teacher education. Another reason for this was that, because of the traditional link between research and teaching in higher education (Healey, 2005), teacher education at universities is considered ideal for providing competencies for engaging with (and, of course, in) research.

To help close this gap, we will present results from a pilot study at two teacher training institutions in England that aimed at gaining insights into:

- how research-competent English teachers in training are;

- how useful they perceive evidence from educational research to be;

- how self-confident they are about engaging with data and evidence; and

- how negatively they feel about research evidence.

Methods – what we did

This study was conducted online at Durham University (2020: N = 59 students in the Primary Teacher Education Programme) and Bath Spa University (2022: N = 11 students in the School-Centred Initial Teacher Training Programme). Participants were recruited upon request in lectures. Participation was voluntary and anonymous, and no biographic data was collected.

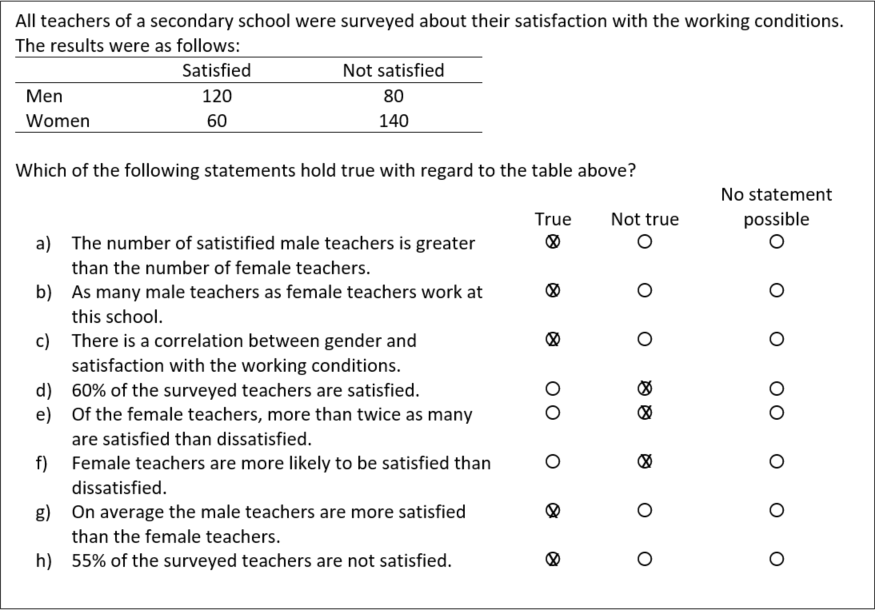

The test booklet consisted of 13 tasks (three, five and five relating to Information Literacy, Statistical Literacy and Evidence-Based Reasoning respectively) based on original research abstracts, data charts and diagrams, or statements about data- or evidence-based conclusions. We provide an example in Figure 1 of a Statistical Literacy task, where statements such as ‘The number of satisfied male teachers is greater than the number of female teachers’ have to be appraised as to whether they reflect the results in the given four-field table. In the given exemplary statement, the absolute number of satisfied people must be compared between men and women, according to which more male (N = 120) than female (N = 60) teachers are satisfied with the working conditions at the school in question.

The compilation of test items was based on their psychometric quality in the original standardisation study in Germany (Groß Ophoff et al., 2017), and some items were adapted thematically to the English context. Partial points were awarded for correct answers so that a maximum score of 30 points could be achieved. The processing time was set up for a maximum of 30 minutes.

In addition, research-related attitudes were surveyed via 12 statements (five-point scale). Eight of these were taken from Brown et al.’s survey item pool[26] and addressed topics like the insufficient benefit of research evidence to teaching and learning (e.g. ‘I don’t believe that research evidence can have any positive impact on teaching practice’) or the understanding of research methods (e.g. ‘I feel confident to judge the quality of research evidence’). Four more items were developed with particular focus on negative feelings or even anxiety towards research (e.g. ‘The idea of engaging with research makes me anxious’).

Analysis – how we made sense of the outcomes

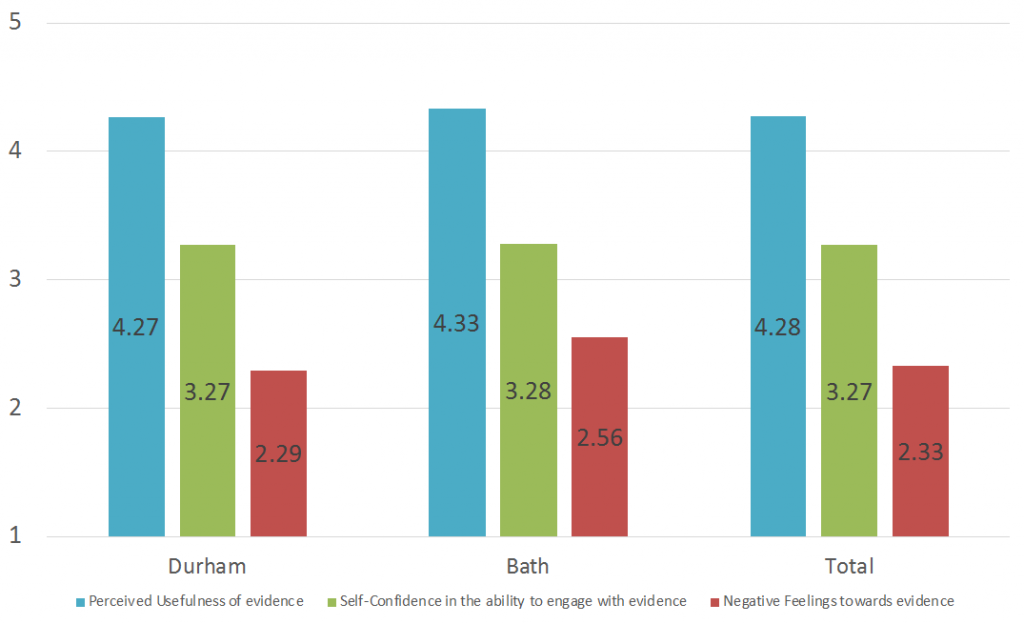

For the standardised competency test, sum scores were calculated, and the percentage of correct solutions was derived based on the number of tasks processed. The survey items were jointly analysed via exploratory factor analysis[ii], based on which three subscales of research-related attitudes could be distinguished: 1) ‘Perceived Usefulness of Evidence‘[iii], 2) ‘Self-Confidence in the Ability to Engage with Evidence‘[iv] and 3) ‘Negative Feelings Towards Evidence‘.[v]

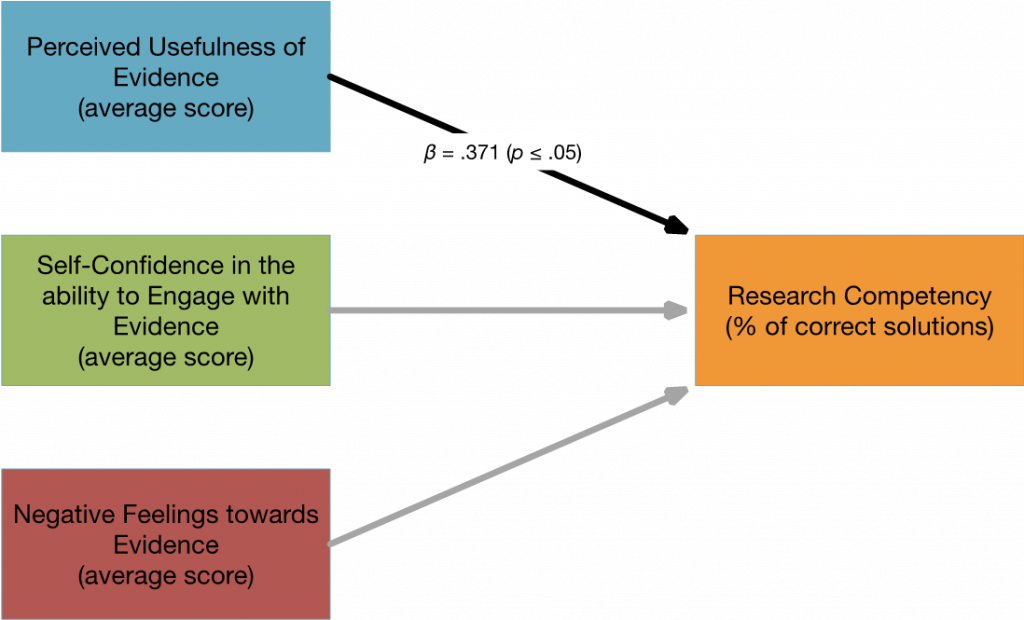

For further analysis, the subscale means were calculated and then used as predictors of the competency test performance in a path model. In Table 1, the correlations between the research competency score and the survey subscale means are reported. As would be expected, the subscale ‘Negative Feelings Towards Evidence‘ is negatively associated with the other, rather positive attitudes concerning research evidence. In other words, negative feelings towards research appear to go hand in hand with the perception that research is less useful, but also with the belief that one is less self-efficient in dealing with data.

Table 1: Correlations Between Research Attitude Dimensions and Research Competency

| Perceived Usefulness of Evidence (F1) | Self-Confidence in the Ability to Engage with Evidence (F2) | Negative Feelings Towards Evidence (F3) | Research Competency | |

| F1 | [.82] | .14 | -.36 | .38 |

| F2 | [.88] | -.51 | .12 | |

| F3 | [.75] | -.16 |

Results – what we found out

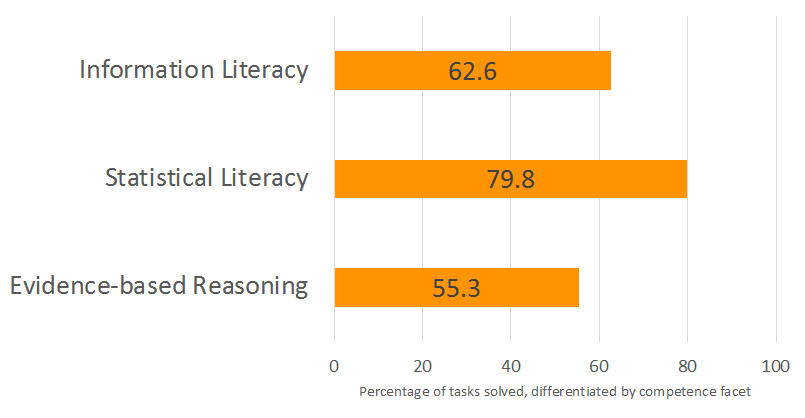

In the standardised assessment of research competency, the teacher training students in this sample completed 65% of 30 tasks correctly. For comparison, students in the German standardisation sample (N = 1,360 university students in Educational Sciences) scored comparatively lower, as approximately only 50% of the same tasks could usually be solved. In this study, participants showed the best performance in Statistical Literacy (on average, 79.8%; see Figure 2) and the lowest performance in Evidence-Based Reasoning (55.3%).

Both in the field of Information Literacy and Evidence-Based Reasoning, Bath Spa University students scored slightly lower than students from Durham (IL: 59% vs. 63%; ER: 52% vs. 56%), but these differences did not prove significant.

Regarding research-related attitudes, teacher training students in this study perceived research evidence as rather useful for their practice (e.g. ‘Research evidence can provide me with ideas and inspiration for improving my practice’), were moderately self-confident in their ability to engage with evidence (‘I feel confident to judge the quality of research evidence’), but reported no distinct negative feelings towards research (‘The idea of engaging with research makes me anxious’).

Again, there were no significant differences between the two groups of teacher training students, but there was an indication of second career teachers (Bath Spa University) having more negative feelings towards research evidence – but due to the small sample size (NBath = 9), this finding cannot be generalised.

Path analysis indicates further that the affective-motivational characteristics contribute to the (statistical) explanation of the level of research competency.[vi] However, only the Perceived Usefulness of Evidence emerged as a meaningful (that is, significant) predictor of research competency. In other words, the more teacher training students were convinced that research evidence can provide ideas and inspiration to improve practice and lead to improved student outcomes, the more research-competent they turned out to be.

What new understanding we gained

From our study, it can be inferred that research competencies are already in place – at least regarding the teacher training students from Durham and Bath Spa who participated in this pilot study. Still, there appears to be room for improvement, especially in Evidence-Based Reasoning, but also in Information Literacy. While the former refers to the ability to formulate appropriate (research) questions and to search and evaluate necessary information[27], the latter represents the ability to substantiate reasoning or critically evaluate given conclusions according to scientific quality criteria. This is precisely the field for which great general difficulties in dealing with data and evidence are reported.[28]

Nevertheless, our findings about research-related attitudes in particular are a cause for optimism, as respondents found evidence useful, were confident in engaging with evidence and reported only limited negative feelings towards evidence. In particular, the usefulness of evidence as perceived by teacher training students has also proven to be a meaningful predictor of research competency, which is in line with the current state of knowledge about influences on the use of data and evidence.[29] In other words, it was clear that the more useful evidence was perceived to be, the better the students in Durham and Bath Spa performed in the competency test.

It should also be emphasised that although negative feelings about evidence do not appear to be related to the test results, they do appear to be related to both the perceived usefulness of evidence and students’ self-confidence in being able to engage with evidence. The extent to which this indirectly influences the association between the perceived usefulness of evidence and the actual research competency could not be verified because of the small sample.

In this respect, it is desirable for further research to revisit the research-related attitudes and research competencies investigated here based on larger student cohorts. These might be from different teacher training institutions or study programmes, for example, to gain in-depth insights based on the corresponding curricula as to which areas of competency should be better covered in the future, and which in turn can serve as a sound foundation for reforms of teacher training in England.

Research competency and the research-informed teaching profession

We wrote this article against the backdrop of the global policy movement towards accountability, evaluation and assessment in schools[30], where the feedback of student performance results to teachers and schools is a central element of quality assurance and development efforts in education. In this light, we wondered why so little is still known about how competent teachers – as recipients of data and evidence – are when it comes to engaging with it. Here, we have attempted to show that objective performance tests are already available, can be used in a sensible way and provide meaningful indications of how the targeted competencies can be promoted in teacher training.

Ultimately, engaging with data is only valuable to recipients if they can use it to clarify a question or solve a problem. For this, users must first be aware of and able to identify the issue at hand (see Information Literacy). It is also important for teachers to experience that dealing with evidence is useful. This, however, presupposes that recipients are able to draw valid conclusions from data or evidence and, in doing so, are given the opportunity to discover that practically relevant answers or solutions are to be found (see Evidence-Informed Reasoning). The results of the pilot study presented here are an indication that there is still room for improvement in these facets of research competency. It is the task of teacher training, whether initial or continuing, to impart these competencies.

Dr habil Jana Groß Ophoff is Professor of Educational Sciences at the University College of Teacher Education (Vorarlberg, Austria); Dr Chris Brown is Professor of Education and Head of School at Southampton Education School at the University of Southampton; and Jane Flood is a lecturer on the School-Centred Initial Teacher Training (SCITT) PGCE programme at Bath Spa University and a former headteacher.

[i] Although the words ‘competency’ and ‘literacy’ have slightly different meanings (the first one is more about knowing something, and the second one is more about using knowledge), they are used interchangeably here. The reason is that in German-speaking countries, the term ‘competency’ is often used to mean what is understood as ‘literacy’ in English-speaking contexts.

[ii] Extraction method: Maximum Likelihood; Rotation: Promax. Out of the original 12 items, two items were removed from analysis due to factor loadings not greater than .30[2]. The number of factors to retain was determined using both Kaiser’s (1960) rule of eigenvalues greater than one and Cattell’s (1966) scree test.

[iii] Dimension 1 with 3 items (λmin = .59)

[iv] Dimension 2 with 2 items (λmin = .65)

[v] Dimension 3 with 5 items (λmin = .38)

[vi] F (3) = 2.937; p ≤ .05; R2 (adjusted) = 9.7%

- Philip Davies, ‘What Is Evidence-Based Education?’, British Journal of Educational Studies 47, no. 2 (1999): 108–21.

- Ellen B. Mandinach and Kim Schildkamp, ‘Misconceptions about Data-Based Decision Making in Education: An Exploration of the Literature’, Studies in Educational Evaluation, From Data-Driven to Data-informed Decision Making:Progress in the Field to Improve Educators and Education, 69 (1 June 2021): 100842, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stueduc.2020.100842.

- Jana Groß Ophoff, Chris Brown, and Christoph Helm, ‘Do Pupils at Research-Informed Schools Actually Perform Better? Findings from a Study at English Schools’, Frontiers in Education 7 (2023), https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2022.1011241; Marieke Van Geel et al., ‘Assessing the Effects of a School-Wide Data-Based Decision-Making Intervention on Student Achievement Growth in Primary Schools’, American Educational Research Journal 53, no. 2 (2016): 360–94.

- Karee E. Dunn et al., ‘Disdain to Acceptance: Future Teachers’ Conceptual Change Related to Data-Driven Decision Making’, Action in Teacher Education 41, no. 3 (2019): 193–211.

- Chris Brown, ‘Research Learning Communities: How the RLC Approach Enables Teachers to Use Research to Improve Their Practice and the Benefits for Students That Occur as a Result’, Research for All 1, no. 2 (2017): 387–405; Rick Mintrop and Elizabeth Zumpe, ‘Solving Real-Life Problems of Practice and Education Leaders’ School Improvement Mind-Set’, American Journal of Education 125, no. 3 (1 May 2019): 295–344, https://doi.org/10.1086/702733; Kim Schildkamp and Amanda Datnow, ‘When Data Teams Struggle: Learning from Less Successful Data Use Efforts’, Leadership and Policy in Schools 21, no. 2 (2022): 147–66.

- Jori S. Beck and Diana Nunnaley, ‘A Continuum of Data Literacy for Teaching’, Studies in Educational Evaluation, From Data-Driven to Data-informed Decision Making:Progress in the Field to Improve Educators and Education, 69 (1 June 2021): 100871, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stueduc.2020.100871.

- Lee S. Shulman, ‘Knowledge and Teaching: Foundations of the New Reform’, Harvard Educational Review 57, no. 1 (1987): 15.

- Christopher Deluca, Danielle LaPointe-McEwan, and Ulemu Luhanga, ‘Teacher Assessment Literacy: A Review of International Standards and Measures’, Educational Assessment, Evaluation and Accountability 28, no. 3 (2016): 251–72.

- Marieke van Geel, Adrie J. Visscher, and Bernard Teunis, ‘School Characteristics Influencing the Implementation of a Data-Based Decision Making Intervention’, School Effectiveness and School Improvement 28, no. 3 (2017): 443–62.

- Jane M. Watson and Rosemary A. Callingham, ‘Statistical Literacy: A Complex Hierarchical Construct’, Statistics Education Research Journal 2, no. 2 (2003): 3–46.

- Gary Shank and Launcelot Brown, Exploring Educational Research Literacy (New York, NY: Routledge, 2007).

- Jana Groß Ophoff et al., ‘Assessment of Educational Research Literacy in Higher Education. Construct Validation of the Factorial Structure of an Assessment Instrument Comparing Different Treatments of Omitted Responses’, Journal for Educational Research Online 9, no. 2 (2017): 35.

- Franziska Böttcher and Felicitas Thiel, ‘Evaluating Research-Oriented Teaching: A New Instrument to Assess University Students’ Research Competences’, Higher Education 75, no. 1 (2018): 91–110; Joanne Gleeson et al., ‘School Educators’ Engagement with Research: An Australian Rasch Validation Study’, Educational Assessment, Evaluation and Accountability, 2023, 1–27, https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11092-023-09404-7.

- Christopher DeLuca and Sandra Johnson, ‘Developing Assessment Capable Teachers in This Age of Accountability’, Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice 24, no. 7 (2017): 121–26.

- Chad M. Gotch and Brian F. French, ‘A Systematic Review of Assessment Literacy Measures’, Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice 33, no. 2 (2014): 14–18, https://doi.org/10.1111/emip.12030; Todd D. Reeves and Sheryl L. Honig, ‘A Classroom Data Literacy Intervention for Pre-Service Teachers’, Teaching and Teacher Education 50 (2015): 90–101.

- Christopher Gess, Christoph Geiger, and Matthias Ziegler, ‘Social-Scientific Research Competency: Validation of Test Score Interpretations for Evaluative Purposes in Higher Education.’, European Journal of Psychological Assessment 35, no. 5 (2019): 737; Sarah Von der Mühlen et al., ‘Judging the Plausibility of Arguments in Scientific Texts: A Student–Scientist Comparison’, Thinking & Reasoning 22, no. 2 (2016): 221–49.

- Groß Ophoff et al., ‘Assessment of Educational Research Literacy in Higher Education. Construct Validation of the Factorial Structure of an Assessment Instrument Comparing Different Treatments of Omitted Responses’.

- Jana Groß Ophoff et al., ‘Assessing the Development of Educational Research Literacy: The Effect of Courses on Research Methods in Studies of Educational Science’, Peabody Journal of Education 90, no. 4 (2015): 560–73; Daniel Kittel, Wolfram Rollett, and Jana Groß Ophoff, ‘Profitieren Berufstätige Lehrkräfte Durch Ein Berufsbegleitendes Weiterbildendes Studium in Ihren Forschungskompetenzen?’, Bildung & Erziehung 70 (2017): 437–52.

- Jana Groß Ophoff and Colin Cramer, ‘The Engagement of Teachers and School Leaders with Data, Evidence and Research in Germany’, in The Emerald International Handbook of Evidence-Informed Practice in Education, ed. Chris Brown and Joel R. Malin (Emerald, 2022), 175–96.

- Mark A. Earley, ‘A Synthesis of the Literature on Research Methods Education’, Teaching in Higher Education 19, no. 3 (3 April 2014): 242–53, https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2013.860105.

- British Educational Research Association, ‘Research and the Teaching Profession: Building the Capacity for a Self-Improving Education System. Final Report of the BERA-RSA Inquiry into the Role of Research in Teacher Education’ (London: BERA-RSA, 2014), Appendix 2, https://www.thersa.org/globalassets/pdfs/bera-rsa-research-teaching-profession-full-report-for-web-2.pdf.

- Pete Boyd, ‘Teachers’ Research Literacy as Research-Informed Professional Judgment’, in Developing Teachers’ Research Literacy: International Perspectives, ed. Pete Boyd, Agnieszka Szplit, and Zuzanna Zbróg (Kraków: Wydawnictwo Libron, 2022), 17–43, https://insight.cumbria.ac.uk/id/eprint/6368/1/Teachers’%20Research%20Literacy%20Prologue%20and%20Chapter%20One%20Pete%20Boyd.pdf.

- Michele Gregoire, ‘Is It a Challenge or a Threat? A Dual-Process Model of Teachers’ Cognition and Appraisal Processes during Conceptual Change’, Educational Psychology Review 15, no. 2 (2003): 147–79.

- Chris Brown et al., ‘Facilitating Research-Informed Educational Practice for Inclusion. Survey Findings From 147 Teachers and School Leaders in England’, Frontiers in Education 7 (2022), https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2022.890832.

- David N. Aspin and Judith D. Chapman, ‘Lifelong Learning: Concepts and Conceptions’, International Journal of Lifelong Education 19, no. 1 (1 January 2000): 2–19, https://doi.org/10.1080/026013700293421.

- Brown et al., ‘Facilitating Research-Informed Educational Practice for Inclusion. Survey Findings From 147 Teachers and School Leaders in England’.

- Groß Ophoff et al., ‘Assessment of Educational Research Literacy in Higher Education. Construct Validation of the Factorial Structure of an Assessment Instrument Comparing Different Treatments of Omitted Responses’.

- Katrin Hellrung and Johannes Hartig, ‘Understanding and Using Feedback–A Review of Empirical Studies Concerning Feedback from External Evaluations to Teachers’, Educational Research Review 9 (2013): 174–90.

- Rilana Prenger and Kim Schildkamp, ‘Data-Based Decision Making for Teacher and Student Learning: A Psychological Perspective on the Role of the Teacher’, Educational Psychology 38, no. 6 (3 July 2018): 734–52, https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2018.1426834.

- DeLuca, Christopher, and Sandra Johnson. ‘Developing Assessment Capable Teachers in This Age of Accountability’. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice 24, no. 7 (2017): 121–26.

Register for free

No Credit Card required

- Register for free

- Free TeachingTimes Report every month