Strengthening Reading Skills At Secondary School

Many people assume that reading is often a skill learned by students in preschool or primary school. As a secondary teacher, I too believed this to be true and, as a result, I never thought that my role as a secondary teacher required me to teach reading. Moreover, I lacked the expertise to instruct students in how to read because it was not something that was part of my formal training as a teacher.

However, in my time as a secondary teacher, I’ve seen many students who struggle with reading. When these students were tested using a diagnostic reading assessment, it revealed that they were often reading below grade level. Sometimes, they were reading several grades below grade level.

Research cites that ‘when students’ reading difficulties persist beyond primary school, the time and intensity needed to remediate these difficulties is challenging to manage in secondary schools’ (Main et al., 2023, p. 89). This situation presents a dilemma for me as I am tasked with helping my students achieve proficiency in the curriculum skills designated for their grade, despite their reading abilities falling below the expected level for that grade.

Lacking extra time for supporting struggling readers, with limited external resources available both within and outside the school to bolster their reading abilities – and facing the responsibility of ensuring my students meet grade-level curriculum standards – I sought out strategies to implement within my classroom.

The strategies that proved effective included those that aimed to entice readers to read, thereby enhancing their reading confidence, as well as strategies that explicitly modelled the behaviours proficient readers engage in during the reading process.

Building Reading Desire and Confidence

As educators, we frequently encounter the challenge of assisting students who face difficulties with reading, particularly because many of these students exhibit reluctance towards engaging with written material. Reynolds (2021) suggests that in the past, individuals with lower proficiency levels may have been encouraged to repeatedly re-read texts. This approach may have inadvertently drawn attention to the students’ struggles, leading to potential embarrassment amongst their peers, or it may have diminished the joy of teaching altogether.

Consequently, I have observed that these struggling readers often attempt to evade reading tasks by resorting to extended bathroom breaks or by immersing themselves in mobile technology. This highlights the necessity of cultivating a genuine desire to read among these students.

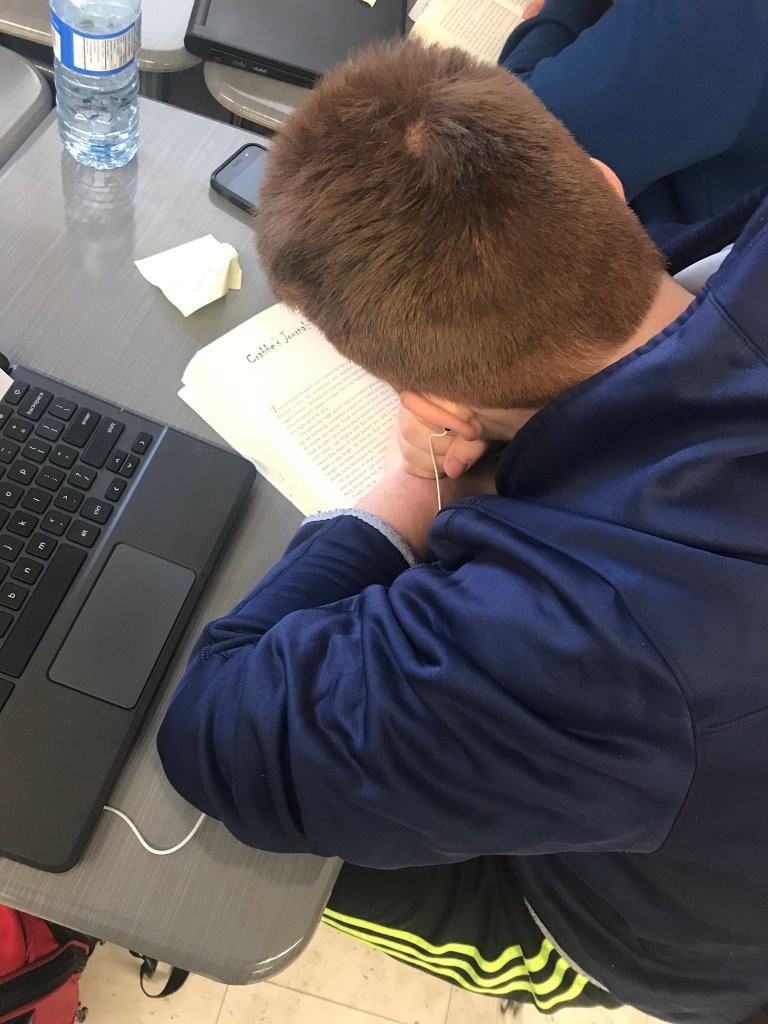

Use audiobooks coupled with print text

Many students enter secondary school grades with deficiencies in reading abilities, exhibiting challenges in comprehension, word recognition, decoding and fluency (Manset-Williamson & Nelson, 2005). Students who struggle with slow and laboured word recognition often expend mental energy decoding text, which hinders their ability to comprehend it (Rasinski, 2003).

Audiobooks engage various senses at once, enabling struggling readers to process information through auditory channels instead of solely relying on written text. This multisensory method has the potential to improve comprehension and retention, especially for students who struggle with decoding written words. By offering accessible alternatives, audiobooks eliminate obstacles to comprehension, granting weak readers access to content that might otherwise be challenging for them to understand.

When having students listen to text, it’s important to ensure the student has the print book or transcript to follow along with. Following along with the printed text helps reinforce the text visually, allowing students to make connections between spoken words and written text. This practice strengthens vocabulary, word recognition, and reading fluency while providing additional support for decoding unfamiliar words. This multi-sensory approach through the co-presentation of audiobooks with print leads to increased reading comprehension (Singh & Alexander, 2022). Enhancing comprehension leads to improved understanding, which in turn makes reading more enjoyable for struggling readers, ultimately encouraging them to read more.

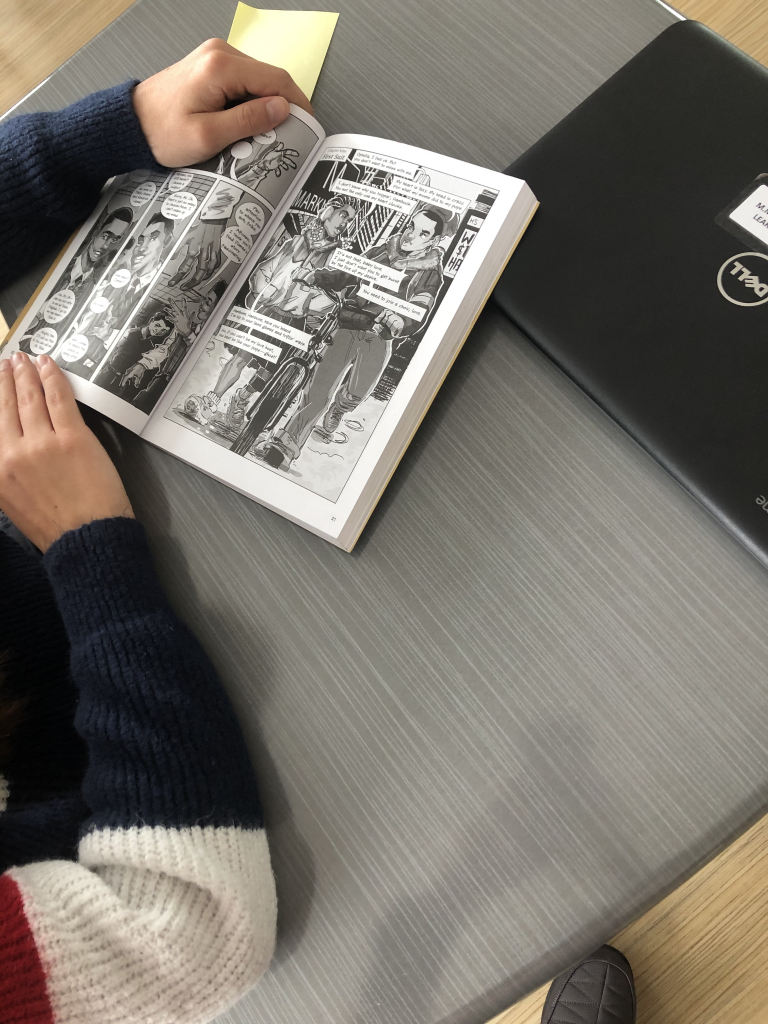

Offer a variety of reading materials with images

To support struggling readers in developing their reading skills, it is important to get them reading. The amount of time spent reading is positively associated with reading achievement and accelerates students’ growth in reading skills (Anderson, et al., 1988). As such, it is important to offer a variety of reading materials for students. Anderson et al. (1988) discovered that students demonstrated improvements in reading achievement regardless of whether they were reading comics or traditional books.

Offering a variety of reading materials that incorporate visual elements, such as books, magazines and graphic novels, can be beneficial. Texts supplemented with images serve as an entry point for reluctant readers, enticing them with visually engaging content. This enjoyable and memorable reading experience not only encourages them to explore additional texts but also fosters a sense of identity as readers.

Visual cues provided by images enhance comprehension of crucial elements and facilitate higher-order thinking (Pantleo, 2014). In traditional texts, students often encounter challenges in identifying elements like climax, themes, characters and setting. Texts supplemented with graphics enable students to improve their ability to recognize these elements and enhance their learning. For instance, in a book featuring black and white illustrations, the sudden introduction of a red image signals a plot development to the reader.

A snapshot of a conversation in my classroom:

Heba: ‘Whoa. Have you gotten to page 27 yet?’

Sunish: ‘No. Why?’

Heba: ‘There’s red in the frames!’

Sunish: ‘What? I thought this novel was all black and white.’

Heba: ‘Me too, but it’s not.’

Sunish: ‘Okay. Shhhh. Probably something big is going to happen. Let me read and get there.’

(After 10 minutes…)

Sunish: ‘I’m on page 30.’

Heba: ‘And… what do you think?’

Sunish: ‘I think it shows her anger. She was always low-key calm and now she’s not. Things are going to get interesting now.’

Heba: ‘I wonder what she’s going to do now that she’s so angry.’

What this discussion underscores is how texts with graphics stimulate readers to discuss and delve deeper into their reading, fostering a desire to engage with the material. These texts not only empower students to actively participate in literary discussions but also encourage collaborative meaning-making among peers.

Additionally, today’s learners need to be able to read images. Students today are bombarded with billboards, memes, magazine ads and commercials. While reading texts with graphics, students learn to decipher images by understanding symbolism, angles and contrast. These skills equip today’s students to also become active, rather than passive, consumers of other forms of media. Perhaps most importantly, empowering struggling readers to extract meaning from texts and actively participate in discussions significantly boosts their reading confidence but also fosters a sense of joy for reading.

Connect reading to real-life experiences

Educators should recognise that not all students naturally enjoy reading and they therefore need a compelling reason to engage with it. Providing students with purposeful and age-appropriate educational materials is essential to maximise their reading experience and learning outcomes. By assisting students in bridging the gap between their reading material and their personal lives or the world around them, educators can significantly enhance their students’ engagement with the material (Guthrie & Davis, 2003).

For example, in my experience teaching a Grade 11 English class tailored to students with lower reading proficiency, we centred our curriculum around the Driver’s Education Manual. Despite facing reading obstacles, these students exhibited impressive determination in overcoming their challenges. Their shared aspiration to acquire driver’s licenses served as a powerful motivator, underscoring the significance of linking reading materials to students’ real-life goals.

Other texts that have effectively engaged struggling secondary students in reading include job advertisements, as many are actively seeking part-time employment; political speeches for candidates in upcoming elections, allowing them to participate in civic discussions with voting family members; and materials related to apprenticeships, colleges, or universities, as they may be exploring post-secondary options.

To instil a lifelong love of reading in students, we must continuously emphasise the multifaceted and deeply rewarding aspects of the reading experience. By implementing these strategies, I have seen noticeable changes in students who were previously reluctant to read due to their weak reading skills. In my experience, I’ve noticed that even though these students encounter difficulties with reading, they actively contribute to class discussions and interact with their peers, leading to a heightened enthusiasm for reading.

This supports the idea that secondary students derive great benefit from instruction that is both socially and cognitively engaging (Baye et al., 2019). As their level of engagement increases, so does their confidence, motivating them to engage in reading more often. Although progress in their reading abilities may occur gradually, its significance lies in fostering a sense of belonging within the classroom setting.

Modelling Proficient Reading Strategies

Reading is an invisible process (Baer, 2005). Often, readers who struggle do so because they don’t know what they should be doing while they are reading. Concepts like visualising while you’re reading to produce mental images (Esrock, 1994), simulating character voices while reading (Kurby et al, 2009) and engaging in active, comprehension-seeking activities while reading (Bristow, 1985) are often traits that proficient readers embody, making it difficult for struggling readers to see how to become a better reader.

Therefore, it is important for secondary students to understand how to enhance their reading skills – a task that is achievable when secondary teachers make the invisible process of active reading visible by reading out loud and scaffolding the reading.

Read out loud to students

The practice of reading aloud is commonly associated with primary grades, but it tends to diminish as students progress to secondary school, where teachers often abandon expressive reading that portrays emotions and distinguishes characters’ voices.

Prosody involves ‘the use of one’s voice to convey meaning to a listener during oral speech or reading’ (Rasinski, 2012, p. 519). Prosodic oral reading begins with comprehension, particularly focusing on grasping the main characters and the challenges they encounter. Pikulski and Chard (2005) argue that fluency serves as the crucial link between word recognition and comprehension. Son and Chase (2018) found that when teachers model prosodic reading, students are able to work with a partner to engage in prosodic reading. This nurtures enthusiasm for reading among developing readers.

Expanding on this, it is possible that when struggling readers comprehend that a character’s voice conveys emotions and reveals plot, they may engage in prosodic reading mentally, thereby enhancing comprehension, engagement and skill.

Further, at the secondary level, when a teacher reads out loud, they can draw attention to syntax and structure. Drawing students’ attention to these facets of a text can increase reading comprehension. Reynolds (2021) shares a lesson where a teacher read the following sentence out loud to students: ‘Its mountains are stark and black, as black as the sea itself, lit only by their peaks by a thin, patchy, covering of white, the skeletal remains of tiny microscopic animals that once lived at the surface’ (p. 523). It wasn’t until students heard it read aloud that a student could recognise that ‘the thin patchy covering of white is the tiny microscopic animals’ (Reynolds, 2021, p. 523).

Whenever my students read a fictional text (whether it is a short story, a novel or a monologue), I always read an excerpt out loud to not only hook my learners into the new text, but also to support my struggling readers by establishing characters and tone. Although reimagining the role of expressive reading in secondary education can contribute to a more enriching and effective learning experience for all students, my primary focus is to teach prosody to struggling readers in a way to not identify them as such to their peers.

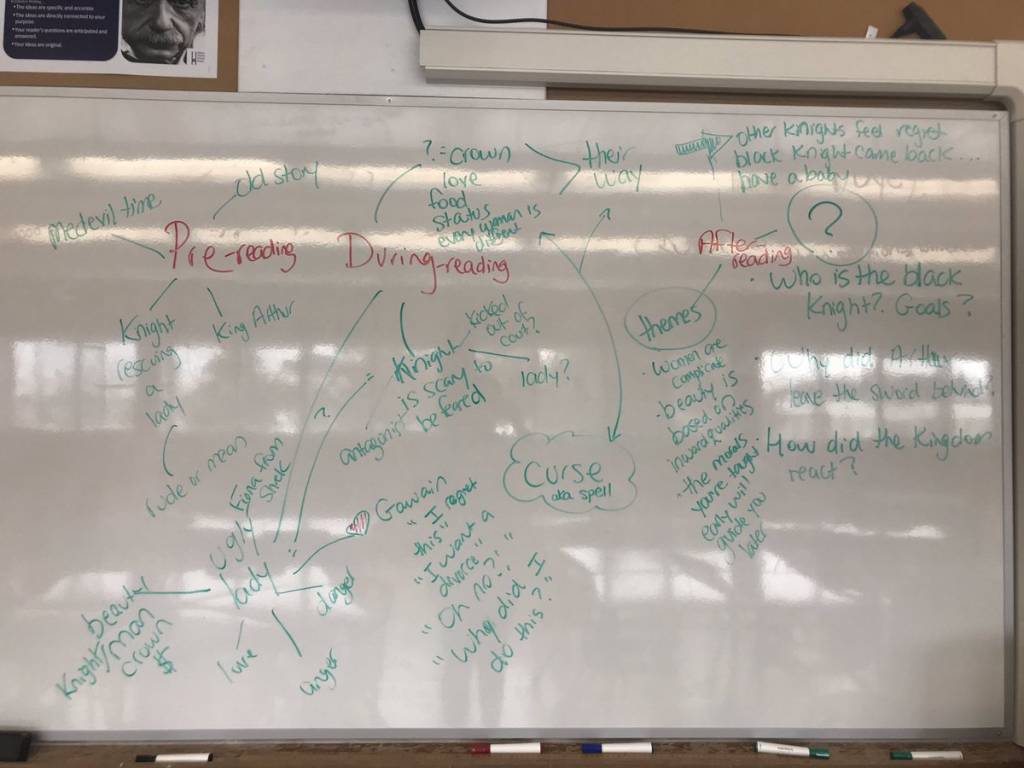

Scaffold reading experiences

When you look at someone reading, it is difficult to know what they are doing while they are reading because reading appears to be a passive activity. However, reading is deeply active with good readers employing various strategies that take place internally in the mind. This can be challenging for a struggling reader because they cannot see what they should be doing while they are reading.

As such, making one’s thoughts visible can support cognition (Kirsh, 2010). Therefore, it’s crucial for educators to explicitly teach the skills of active reading, empowering students to navigate texts more effectively and comprehend them deeply. Nerlino (2023) found that when she explicitly taught students strategies to engage in active reading it fostered student engagement and ownership of the reading process and created a class reading culture.

As a secondary teacher, it was common for me to have students read a text and then participate in activities and discussions to analyse the text after they had read it. However, I noticed that my struggling readers just wouldn’t read the text or if they read it, they couldn’t remember what they read. As such, I needed to break the reading process down by utilising scaffolding techniques which are effective in supporting students in developing their reading skills (Diehl et al., 2011). Starting with pre-reading activities to activate prior knowledge and conceputalise prior content knowledge deepens understanding of the text (McCarthy & McNamara, 2021).

Segmenting texts into manageable chunks can also be extremely helpful for struggling readers (Casteel, 1990). Throughout the reading process, it is helpful to encourage ongoing discussions to reinforce comprehension (Duke et al., 2021), foster critical thinking (Moghadam et al., 2023) and cultivate a collaborative learning environment. This comprehensive approach aids students in navigating complex texts, enhances engagement and facilitates deeper understanding. Using a beginning-middle-end (BME) scaffolding approach fosters fluency and comprehension for readers (Son & Chase, 2018).

In my experience, I’ve found that it also helps to make the reading process visible by explicitly showing my students what happens in my mind when I’m reading. Recently, I read a short story out loud and paused after every page to map out my entire active reading process (Sharma, 2023). My goal was to try to make the invisible visible to my students. This allowed me to notice how learning how to be active readers empowers students to take control of their own learning. It gives them the tools and confidence to tackle challenging texts independently, promoting self-reliance and a sense of achievement.

Modelling proficient reading strategies is essential for secondary educators aiming to empower students in strengthening their reading skills. By incorporating strategies such as prosodic oral reading while scaffolding reading experiences, I’ve seen previously reluctant readers engage in discussions about reading that foster a collaborative learning environment.

This adds to the idea that secondary students benefit from reading instruction that is socially and cognitively engaging (Baye et al., 2019). By making the reading process visible, educators empower students to take ownership of their learning and, in turn, develop the confidence to tackle reading complex texts independently. Ultimately, this promotes a culture of self-reliance and academic achievement.

In conclusion, despite my initial assumptions that reading instruction is the domain of primary educators, as a secondary teacher, I’ve come to recognize the critical role I play in supporting struggling readers. Through my journey, I’ve encountered the challenges posed by students reading below grade level and the limited resources available for remediation in secondary settings. However, by implementing strategies that foster a desire to read and explicitly model proficient reading behaviours, I’ve witnessed significant improvements in my students’ reading confidence and skills.

Moving forward, amidst the decline in reading scores observed in Canada, the US and the UK (as revealed in The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s (2022) data) and with Ontario officially recognising reading as a human right, it becomes imperative for secondary teachers to foster environments where all students can actively participate in reading, regardless of their current proficiency level. This necessitates the creation of inclusive opportunities that cater to students reading below their grade level, ensuring equitable access to literacy resources and support.

By embracing these principles and continuing to refine our instructional approaches, we can empower all students to become confident and proficient readers, thereby laying the foundation for their academic success and lifelong learning journey.

Sunaina Sharma is a seasoned educator and school leader with over two decades of experience who prioritises the needs of her learners above all else. When faced with disengaged students, she adopts a proactive approach by asking: ‘What if?’ This enables her to implement interventions, evaluate their effectiveness and refine her teaching strategies accordingly. Through this process, Sunaina not only enhances the classroom environment but also fosters a culture of empowerment, encouraging her students to embrace risk-taking and exploration.

Anderson, R. C., Wilson, P. T., and Fielding, L. G. (1988). Growth in reading and how children spend their time outside of school. Reading Research Quarterly. 23(3), 285-303. https://doi.org/10.1598/RRQ.23.3.2

Baer, A. L. (2005). Do You Hear Voices? A study of the symbolic reading inventory. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 49(3), 214–225. https://doi.org/10.1598/JAAL.49.3.5

Baye, A., Inns, A., Lake, C., & Slavin, R. E. (2019). A synthesis of quantitative research on reading programs for secondary students. Reading Research Quarterly, 54(2), 133-166. https://doi.org/10.1002/rrq.229

Casteel, C. A. (1990). Effects of Chunked Text-Material on Reading Comprehension of High and Low Ability Readers. Reading Improvement, 27(4), 269–275.

Diehl, H. L., Armitage, C. J., Nettles, D. H., & Peterson, C. (2011). The three-phase reading comprehension intervention (3-RCI): A support for intermediate-grade word callers. Reading Horizons, 51(2), 149-.

Duke, N. K., Ward, A. E., & Pearson, P. D. (2021). The science of reading comprehension instruction. The Reading Teacher, 74(6), 663–672. https://doi.org/10.1002/trtr.1993

Esrock, E. J. (1994). The reader’s eye : visual imaging as reader response. Johns Hopkins University Press.

Guthrie, J. T., & Davis, M. H. (2003). Motivating struggling readers in middle school through an engagement model of classroom practice. Reading & Writing Quarterly, 19(1), 59–85. https://doi.org/10.1080/10573560308203

Kirsh, D. (2010). Thinking with external representations. AI & Society, 25(4), 441–454. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-010-0272-8

Kurby, C. A., Magliano, J. P., & Rapp, D. N. (2009). Those voices in your head: Activation of auditory images during reading. Cognition, 112(3), 457–461. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2009.05.007

Main, S., Hill, S., & Paolino, A. (2023). Improving the reading skills of struggling secondary students in a real-world setting: issues of implementation and sustainability. Australian Journal of Learning Difficulties, 28(1), 73-95. https://doi.org/10.1080/19404158.2023.2210588

Manset-Williamson G., Nelson J. M. (2005). Balanced, strategic reading instruction for upper-elementary and middle school students with reading disabilities: A comparative study of two approaches. Learning Disability Quarterly, 28(1), 59–74. https://doi.org/10.2307/4126973

McCarthy, K. S., & McNamara, D. S. (2021). The multidimensional knowledge in text comprehension framework. Educational Psychologist, 56(3), 196–214. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.2021.1872379

Moghadam, Z. B., Narafshan, M. H., & Tajadini, M. (2023). The effect of implementing a critical thinking intervention program on English language learners’ critical thinking, reading comprehension, and classroom climate. Asian-Pacific Journal of Second and Foreign Language Education, 8(1), 15–18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40862-023-00188-3

Nerlino, E. (2023). “Annoying but helpful…”: Action research examining secondary students’ active reading of assigned texts. Educational Action Research, ahead-of-print(ahead-of-print), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/09650792.2023.2209609

Pantaleo, S. (2014). Reading images in graphic novels : taking students to a “greater thinking level?” English in Australia, 49(1), 38–51.

Pikulski, J. J., & Chard, D. J. (2005). Fluency: Bridge between decoding and reading comprehension. The Reading Teacher, 58(6), 510–519. https://doi.org/10.1598/RT.58.6.2

Rasinski, T. V. (2012). Why reading fluency should be hot. The Reading Teacher, 65(8), 516–522. https://doi.org/10.1002/TRTR.01077

Rasinski T. V. (2003). The fluent reader: Oral reading strategies for building word recognition, fluency, and comprehension. Scholastic.

Reynolds, D. (2021). Scaffolding the academic language of complex text: an intervention for late secondary students. Journal of Research in Reading, 44(3), 508–528. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9817.12353

Sharma, S. (2023, March 31). Teaching high school students active reading skills.

Edutopia. https://www.edutopia.org/article/teaching-active-reading-strategies-high-school

Singh, A., & Alexander, P. A. (2022). Audiobooks, print, and comprehension: What we know and what we need to know. Educational Psychology Review, 34(2), 677–715. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-021-09653-2

Son, E. H., & Chase, M. (2018). Books for two voices: Fluency practice with beginning readers. The Reading Teacher, 72(2), 233–240. https://doi.org/10.1002/trtr.1700

The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. (2022). PISA 2022 results: The state of learning and equity in education. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/sites/53f23881-en/index.html?itemId=/content/publication/53f23881-en