Name some famous people with Dyslexia.

You might choose Albert Einstein, Keira Knightley, Sir Richard Branson, Steven Spielberg, Steve Jobs, Princess Beatrice, Bill Gates or Jamie Oliver.

Now name three people who are black and have Dyslexia.

You are probably struggling.

Dyslexia has had a tortuous history. It has long been seen as a condition for the middle classes because in the early days, children were only given the diagnosis of dyslexia if other causes for literacy problems were ruled out. This meant that they were not seen as dyslexic if their parents were divorced (emotional trauma), living in a council house or unemployed (poverty) or in prison (family breakdown).

It goes without saying that children whose parents were from another culture or who were learning English as a second language were unlikely to qualify for a diagnosis.

It is a lifetime ago. Yet, even now, fifty years later, there is a surge in anti-dyslexia rhetoric every few years. The specialist dyslexia schools are still in the southern half of the country and dyslexia role models are predominantly white and middle class.

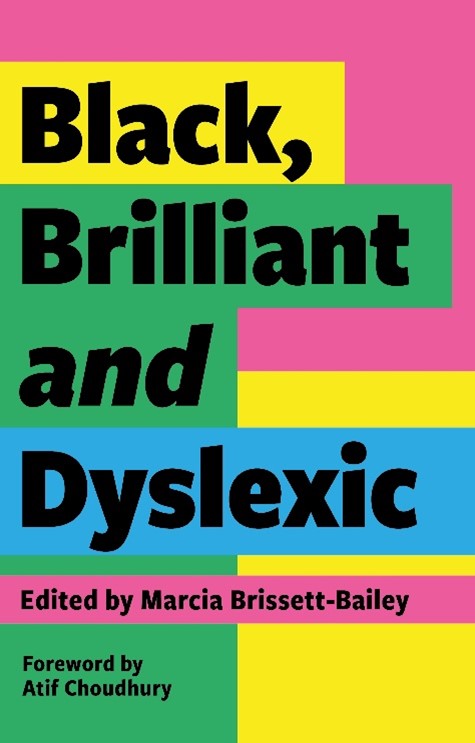

Black, Brilliant and Dyslexic

This is a book of testimonies, life stories and mantras. It is described as ‘a raw, honest and enlightening collection of experiences, across the black and dyslexic community, giving an intersectional perspective.’ Published in February 2023, it is edited by Marcia Brissett-Bailey, winner of the British Dyslexia Association (BDA) Adult Award 2022 and a co-founder of the BDA Cultural Perspective Committee.

There are over 50 contributors, black people on the way up. They have not only come to terms with their dyslexia – and in some cases interrelated conditions such as dyspraxia, ADHD and Tourette’s – but also celebrate the ‘superpowers’ that their neurodiversity has conferred.

Marcia’s story

Marcia Brissett-Bailey was the first member of her family to go to university and gain a degree. She also went on to gain a postgraduate degree in career guidance and a master’s degree in special educational needs and disabilities.

‘At college, my dyslexia was diagnosed. I was 16 and couldn’t have been more relieved. I was no longer ‘stupid’. There was a name for the way I learned and saw the world in pictures. My parents didn’t really understand my diagnosis, nor did they know about dyslexia, but I received weekly support from a lady called Jenny, to whom I will be forever grateful.

‘I felt released from a prison sentence, but I was innocent of the crime, left dealing with crippling emotions. I felt savagely deprived of the opportunity to know who I was and the true potential I carried inside me. came to realize that it wasn’t me that was broken but the system.’

Under pressure

Along the way her family was put under the spotlight by authorities who hinted to her mother that her learning issues ‘were linked to problems at home, possibly abuse.’ Many families with a black child who has anxiety and mental health issues are facing the same prejudices today.

Marcia started to feel an outsider in her school community: ‘Everything that represented me was portrayed as negative. There were no images of anyone who looked like me that represented beauty; people of my skin colour did not achieve academically, according to the statistics.’

Again, this has not changed so much. TeachingTimes has marked Black Hair Day over the last two years by: calling out schools whose uniform policy imposes conformity on those with Afro hair, and working with Pantene on curriculum materials that promote an understanding of the science of hair and celebrate its beauty. However, there are still too many cases where those who look different are treated differently.

Insights for schools

Atif Choudhury, Chief Executive, Diversity and Ability, talks about black children, further marginalised by their neurodiversity looking for a feeling of acceptance and safety in school – and not finding it. Both he and the author Marcia Brissett-Bailey became, ‘selectively mute’ and several other contributors recall the same outcome. The teachers at the time may have seen them as quiet, acquiescent or ‘daydreaming’, but as Choudhury says: ‘the silence of children is expensive; it robs us all. When children repress their voices, a society loses innovation, it loses laughter and, sometimes, it permanently loses participation.

Time and again contributors talk about how important drama was to them as a way to express themselves, to showcase talents such as comedy, creating dialogue, developing characters. but this outlet is now denied to them in many schools.

Angie Le Mar is now a successful British comedian, actor, writer, director, presenter and producer. Drama was her lifeline but: ‘Other subjects were, to me, a complete waste of time, subjects like geography and history. ‘Well,’ I thought, ‘why should I care about learning about a map, when I am not going anywhere? Why should I learn about history if this does not relate to me?’ I thought that until you (the system) deal with the fact that we were taken for slaves, I am not interested.’

Decolonising the curriculum is still in its infancy but it is hard for people to respond positively to a curriculum based on the experiences and values of the dominant ethnic group. Atif Choudhury says: ‘Offering solidarity to neurodiverse people facing learning isolation as they navigate exclusion is an act of justice… The trauma of European imperialism, educational demands and a language commanded and taught down the barrel of a gun continues to echo for generations.’

Attitudes to dyslexia in black communities

Schools and colleges have little awareness of the cultural background of their students. Students of course do not want to draw attention to themselves and the things that make them different. The testimonies of the contributors give a fascinating insight into the perspectives of some of these groups.

Leslie Lewis-Walker says: ‘In most black communities in the western world, it is drilled into us that we must work twice as hard because we are black. At the same time, neurodiversity is sometimes seen as a myth, to the point where we shy away from it, as such topics are rarely discussed.’

When Oladoyin Idowu got a diagnosis of dyslexia, her parents were deeply unhappy: ‘My mum, being very religious, rebuked every spirit of learning disability in me.. They both lived in denial again, in their bid to protect me from society seeing me as disabled… In Nigeria, we would spend more time engaging in rituals, such as binding and casting demons, than attending to an issue that had a solution.’

Jannett Morgan, a black specialist tutor, assessor and workplace coach, shed some light on this: ‘Sadly, many black students are reluctant to seek help (even when they do get to university) until they find themselves in serious difficulty. Some of this is because of stigma within their communities but it is also because of the racist narrative about black people and intelligence and the structural racism in the education system.’

Other contributors had similar experiences: ‘Mum told me from the start that she did not accept that I’m dyslexic’; ‘My culture didn’t believe such a condition existed; they just believed you must study and work twice or three times as hard to catch up, or to be better than your peers’; ‘There was a taboo in having a disability, even a ‘hidden’ one, and in Ghana, physically disabled people were shut away. They were always hidden, not integrated.’

The positives

All too often dyslexia is seen as a negative but in this book there are many positive stories that focus on the creativity, empathy and determination of people with dyslexia.

Maxine Johnson, freelance dyslexia specialist teacher PATOSS says: ‘One advantage that many dyslexic people have is the ability to think outside the box; this enables them to have brilliant and innovative ideas. Furthermore, due to their excellent logical reasoning and visual abilities they are likely to pursue rewarding careers in the mathematical or science fields. It saddens me when someone unwittingly believes that if you have dyslexia, you lack intelligence. This assumption is so far from the truth.‘

Remi Ray of The Diverse Creative Community Interest Company was recognized in 2019 as one of the most influential neurodivergent women in the UK for her contribution to the plus-size fashion world. ‘I decided it was time to create my own path; I took part-time jobs, including working on a market stall, and started to research how to build my own boutique. Trapped in A Skinny World was birthed in 2011, as a plus-sized vintage boutique.’

Overcoming anxieties

Natasha Gooden is a choreographer, dancer, model and actor., Natasha went to Liverpool Community College to study dance. Here she was finally assessed and found she had dyslexia. In 2011 she was cast as Oprah in a West End show called Some Like It Hip Hop. After years of struggling with reading aloud, she was horrified to find she had a monologue: ‘You can only imagine how I felt seeing those words on the page. I wanted the ground to open up and swallow me whole. Only that did not happen. I had to read my part out loud in front of everybody. My heart was racing, my palms were sweating. It was a flashback to my high school English classes. The very thing I wanted to avoid came back around to haunt me but this time there was nowhere to hide. So, I took a deep breath and began to read out loud. Once I had finished, a voice in my head said, ‘See, that was not so bad,’ and I remember being so proud of myself. From that day on, my mental attitude towards myself was so much more positive.

She does not minimise the problems: ‘No one told me that dyslexia would impact most, if not all areas of my life. I struggle to read maps and get lost often. I can’t think when my mind is overstimulated…and there are times when I cannot find the words to tell you what has causedthe overstimulation. I wouldn’t change a thing because dyslexia gifted me creativity.’

Black, Brilliant and Dyslexic Edited by Marcia Brissett-Bailey Paperback February 2023 | £13.99 | 9781839971334

Sal McKeown is author of several books on dyslexia including How to Help Your Dyslexic and Dyspraxic Child published by White Ladder Press

Register for free

No Credit Card required

- Register for free

- Free TeachingTimes Report every month