What are the symptoms of dyslexia?

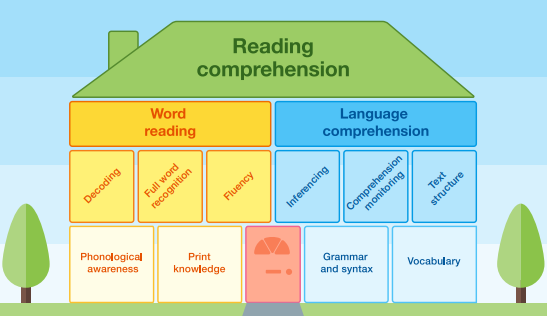

From childhood, persistent difficulties in the acquisition of literacy skills (reading, spelling and writing) can be noted. Lower than expected age-related levels of literacy attainment (e.g. in reading fluency, reading accuracy, reading comprehension, spelling accuracy and writing fluency and accuracy) that persist longer than one year, despite intervention, might therefore be viewed as key specific indicators of a developmental literacy difficulty, or dyslexia. Addressing literacy difficulties involves a multifaceted approach with additional support in reading, writing and comprehension.

Young children can show early signs of difficulty in acquiring alphabetic knowledge and phonological awareness (linking letters and letter combinations to sounds). They have particular difficulty in decoding new and unfamiliar words, and in spelling. This can occur despite having good oral vocabulary and other verbal or non-verbal conceptual skills. They also show weak phonological or visual processing skills.

From around the age of seven, dyslexic learners demonstrate poorly specified phoneme representations that prevent the development of complete and secure mappings between phonemes (sounds) and their corresponding letter strings and inhibit the ‘typical’ move away from reliance on a decoding strategy. So, they rely on ‘phoneme by phoneme’ decoding for much longer than typical learners.

They also experience significant, persisting struggles with reading, writing and spelling, the basis of which lies in multiple interacting factors (e.g. phonological or visual processing deficits, but may also include features of other co-occurring developmental difficulties, such as motor, attentional, language or social and communication difficulties).

Dyslexic learners may show weak phonological memory skills and slow response to intervention. They can begin to acquire negative attitudes to their reading, spelling and writing experiences. They may continue to read slowly and to read and spell very inaccurately. If they have good verbal and oral language skills, they may show few problems with listening comprehension and few problems with reading comprehension, unless under timed pressure or reading speed is exceptionally slow.

Teachers should know their pupils best – they also need to be ‘armed’ with the understanding of how to encourage and support them so they make good progress in their learning journey. We now know there are many supportive strategies that can help dyslexic learners and others with a neurodiverse profile, which should be part of quality first teaching to make an inclusive classroom. Free resources are also available to help teachers develop inclusive practices for their neurodiverse classrooms.[1]

Reading: A Necessary Foundation Skill

Children learning to read have a short developmental ‘window’ between five and nine years of age where crucial learning usually takes place. The longer-term impact of even a short period of developmental delay during these years can be profound. The purpose of identification should always be focused on refining and improving effective interventions. The following criteria, per the SASC Response to the SEN Green Paper 2022[2], can inform when it could be appropriate to refer for assessment:

- Relative to age expectations, a child‘s difficulties in reading accuracy, fluency or reading comprehension have been persisting or worsening for at least six months despite appropriate, sustained and monitored interventions put in place.

- A child appears to be able to sustain progress in literacy acquisition or academic progress in subjects heavily dependent upon literacy acquisition only with a high level of support and intervention.

- A child is showing signs of distress or behavioural difficulties that appear to be linked to difficulties in literacy attainment.

- A child’s difficulties in literacy contrast markedly with other aspects of their achievement profile.

- A range of co-occurring difficulties (developmental, psycho-social, medical) is contributing to a complex picture of need, requiring specialist recommendations for intervention.

- Other (non-developmental) explanations for persisting difficulties have been considered e.g. frequent school moves, frequent school absence due to ill health, trauma, the impact of learning loss during the COVID-19 pandemic, inappropriate or inconsistent instruction/intervention strategies etc.

To ensure continuity of provision, there also needs to be a clearly defined mechanism for the transfer of records of assessment and intervention to class teachers and support staff within and between schools, especially on transfer at Year 7. Regular, frequent review and re-assessment is useful and important. [It] is most effective when informed by previous records.

SASC Response to SEN Green Paper 2022 (accessed 5/2/24)

The years between Year 2 and Year 7 are particularly key to assuring that these children get the right support, or they will fall farther and farther behind, causing a terrible loss of self-esteem. As many of us have seen in our teaching experience, many dyslexic children by the age of 12 are avoidant readers who have experienced low self-esteem that appears to have impacted broader aspects of their lives.

Nearly 20% of adolescents are not able to read simple texts accurately and with understanding. If they are still struggling at that stage they need ‘a model of tiered support, which increases in line with need’ and ‘assessment should be used to match students to appropriate types of intervention with frequent monitoring (their) impact’ on progress (EEF_KS3_KS4_LITERACY_GUIDANCE.pdf, p. 7, accessed 28/1/24).

It is important to note the following:

- The range of reading abilities in Years 5-9 are largely overlapping (but the curriculum demands are not).

- At transition, children need to be prepared for the increased challenge in their language and reading context and the increased expectations they face.

- We can’t assume that children and adolescents have the reading skills needed to access the school curriculum and complete school assessments and exams.

- Teachers in all classrooms face a real challenge in supporting learning for students with such wide-ranging reading abilities (per J Ricketts, 2023 Patoss Conference Keynote, ‘Reading in adolescence: What do we Know and What can we do?’).

- Supporting students with dyslexia in mainstream schools involves a collaborative effort among teachers, parents and specialists. Support must be well-structured and systematic, with frequent opportunities to review to build a firm foundation.

More than just phonics

Supporting dyslexic children is not all about phonics! The Education Endowment Foundation strongly supports this, noting the importance of a varied approach: ‘The purpose of reading is to comprehend the written word, so building vocabulary is also key.’ Where students haven’t mastered the phonics code by the time of the phonics check at the end of Key Stage 1, additional strategies must be put in place as a matter of priority. We cannot afford for these children to leave primary education unable to read well enough to access the secondary curriculum.

Learning to read exerts a reciprocal influence on cognitive abilities (Snowling, 2020).[3] Learning to read at the expected age tends to drive positive orientations to reading and, very likely, to learning in general; these children step onto an ‘up’ escalator. For children who do not begin to learn to read at the expected age, the risk of a reverse motivational trajectory (a ‘down’ escalator’) is high. Looking at the underlying causes of individuals’ reading difficulties facilitates understanding of why decoding requires so much more effort in dyslexic learners and inhibits the reciprocal ‘self-teaching’ process that occurs for typically developing readers.

When learners continue to struggle, they need more than to be taught the same content again. Here is a role for specialist teachers who can help these learners understand where they are struggling and why: help them develop skills in how they learn to encourage the development of autonomy, resilience and self-esteem.

Dyslexic learners have particular weaknesses in phonological awareness and phonological processing. Learning the sounds that letters and letter combinations make (phonics) is necessary but it is not enough for these struggling readers. So they must be provided with additional tools to help them with reading comprehension not based solely on phonics.

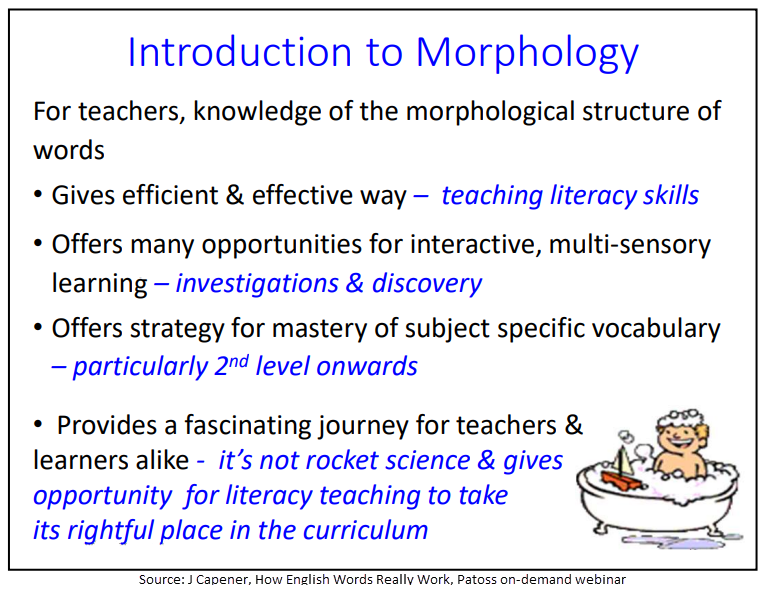

Research has demonstrated the importance of an integrated approach and an understanding of how language works in ensuring mastery of the English language. As Sue Hegland notes in her free webinar: ‘Understanding all aspects of our language will enable you to explain many otherwise mysterious spellings, improving the learning experience for students.’[4]

Understanding how words are built and discovering the connections between word structure and meaning can be a useful way into comprehension for learners who struggle with phonological processing. Using this approach becomes even more important when tackling new vocabulary moving up to secondary education and beyond.

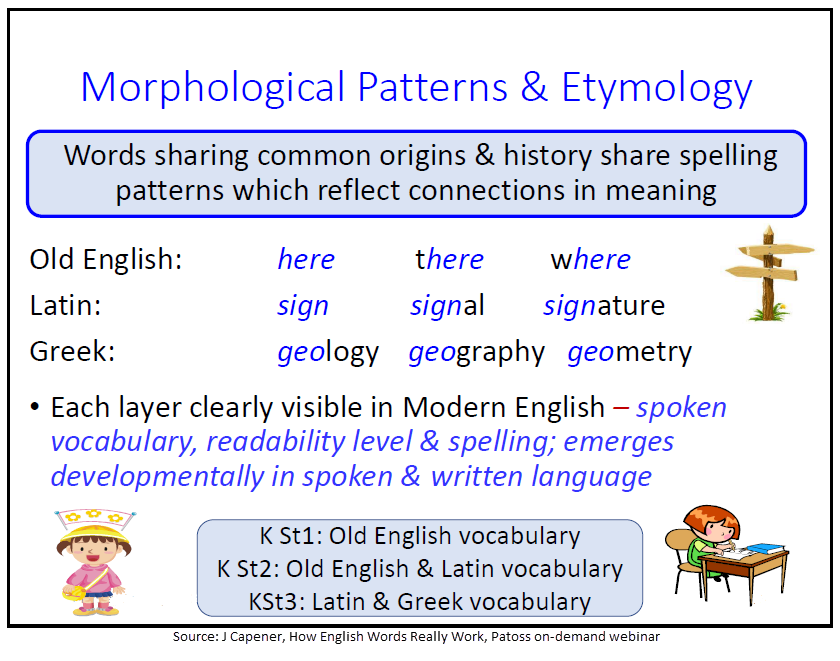

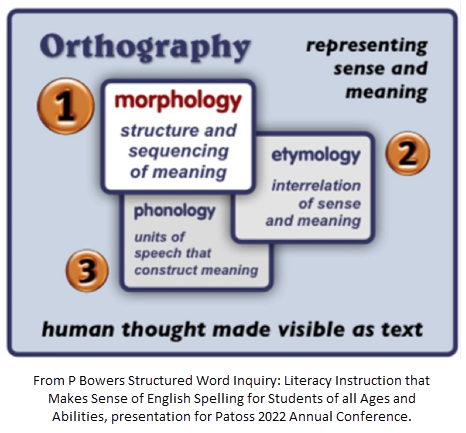

Exploring and understanding the connections between the structures and meanings of words (morphology) and looking at their history and origins (etymology) can be the key that unlocks the door to understanding and spelling. Morphology focuses on the internal structure of words in terms of their meaning. Etymology sheds light on how words relate to each other through their ‘roots’ or origin. Spelling is a way of showing what words mean. Understanding both morphology and etymology helps build vocabulary, reading comprehension and spelling.

In their meta-analysis of morphological approaches, Goodwin and Ahn found that:

Overall, morphological instruction showed a significant improvement on literacy achievement (d = 0.33). Specifically, its effect was significant on several literacy outcomes such as phonological awareness (d = 0.49), morphological awareness (d = 0.40), vocabulary (d = 0.40), reading comprehension (d = 0.24), and spelling (d = 0.20). Morphological instruction was particularly effective for children with reading, learning, or speech and language disabilities, English language learners, and struggling readers, suggesting the possibility that morphological instruction can remediate phonological processing challenges. Other moderators were also explored to explain differences in morphological intervention effects. These findings suggest students with literacy difficulties would benefit from morphological instruction.[5]

Goodwin and Alm (emphasis added)

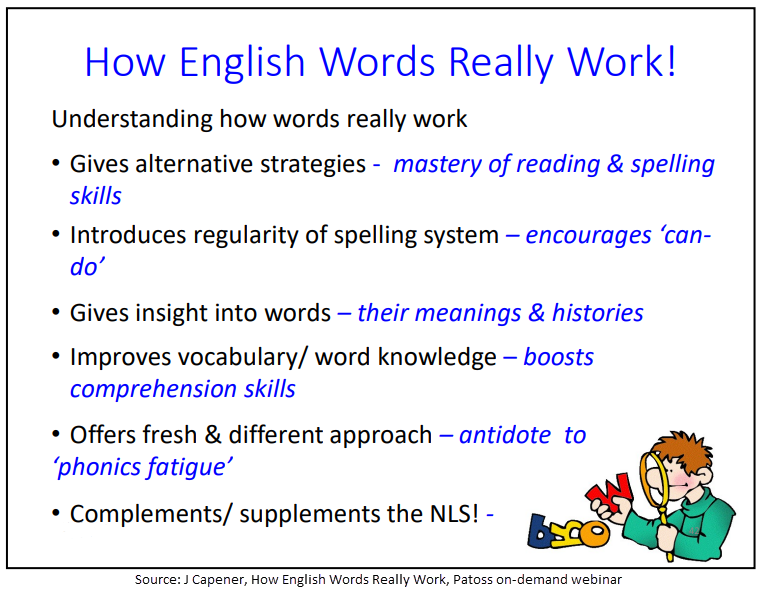

Judy Capener’s ‘How English Words Really Work’, a Patoss OnDemand webinar, is an excellent introduction to these methods.

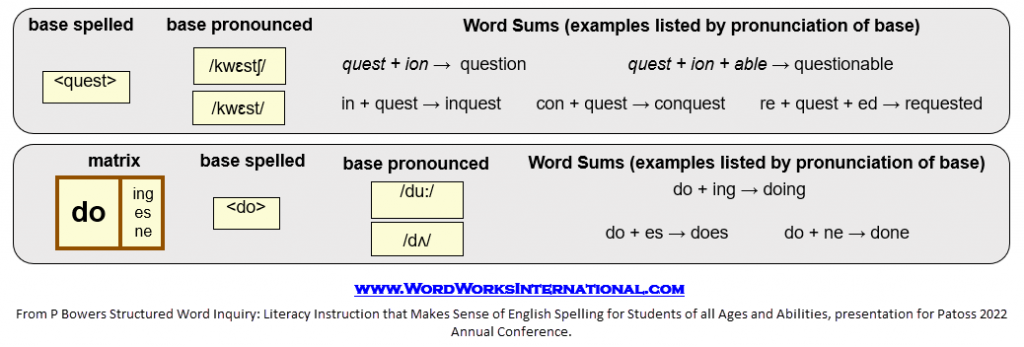

Teaching morphology involves highlighting the parts of words that give meaning and seeing how those words are built using prefixes, suffixes and a root or base word. Research has shown that students can develop their vocabulary while also improving phonological awareness, decoding and spelling (Levesque, K., Breadmore, H. and Deacon S. H. 2021).[6] Using morphology is relevant from the outset for all learners. See the illustrations below for examples of how this approach will help teachers over some of the early hurdles and can help with tricky words at Key Stage 1.

Approaches like Structured Word Inquiry, which also incorporates morphology and etymology, are good models to explore. A useful introduction can be found in Peter Bowers’ webinar (accessible via the Patoss website). This session, delivered by Bowers at the Patoss Annual Conference 2022, addresses the theory and practice of ‘Structured Word Inquiry’ (SWI) and where it fits in relation to research for literacy instruction across age and ability levels. It is suitable for both educators and parents.

Bowers shows how this instruction uses scientific inquiry with linguistic tools to reveal how English spelling links meaningfully related words through the interrelationship of morphology, etymology and phonology. Participants will see how studying words from this linguistic frame explains grapheme-phoneme correspondences typically considered irregular (e.g. rough, one, sign) and how it offers generative vocabulary learning by teaching the spelling-meaning connections between words (e.g. sign, signal, design, signature) as shown in the study that introduced SWI (Bowers & Kirby, 2010).

Bowers explains conventions of English spelling through the same practices used in classrooms around the world. Participants will leave with explicit teaching ideas, but more importantly, they will gain an introduction to a new way to understand and teach how our written word works.

Conclusion

It is important to note that any support for dyslexic learners must be structured and systematic and provide opportunities for review. One of my favourite illustrations can be kept in mind:

Every student with dyslexia is unique, and the strategies that work for one may not work for another. Regular communication and collaboration among educators, specialists and parents are key to creating a supportive and inclusive learning environment for students with dyslexia in mainstream schools.

Lynn Greenwold, OBE, is Vice-Chair of the Board of Directors and Advisor on Policy and Education Development at Patoss (the Professional Association of Teachers of Students with Special Learning Difficulties). She is also Chair of SASC, the SpLD Assessment Standards Committee.[7]

Footnotes

- Teaching for Neurodiversity: Engaging Learners with SEND is a DfE-funded project produced with partners Patoss, Helen Arkell, BDA and Dyslexia Action that has developed resources and delivered a series of Train the Trainer: Teaching for Neurodiversity events at venues around England. These training sessions are available for free as webinars and downloadable resources under Teaching for Neurodiversity on the Patoss website.

- https://www.sasc.org.uk/media/h3zjcxw3/sasc-reponse-to-send-green-paper-july-2022.pdf.

- Snowling, M. J. & Hulme, C. (2020). Annual Research Review: Reading Disorders Revisited – the Critical Importance of Oral Language. Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry, 62(5), 635–653.

- Hegland, S ‘Beneath the Surface of Words: What English Spelling Reveals and Why It Matters’ free webinar available here.

- Goodwin A. P., Ahn S. (2010) ‘A meta-analysis of morphological interventions: effects on literacy achievement of children with literacy difficulties’. Annals of Dyslexia. 2010 Dec; 60(2):183-208. doi: 10.1007/s11881-010-0041-x. Epub 2010 Aug 27. PMID: 20799003.

- Levesque, K., Breadmore, H. and Deacon S. H. (2021) ‘How Morphology Impacts Reading and Spelling: Advancing the Role of Morphology in Models of Literacy Development’, Journal of Research in Reading, 44 (1), pp. 10–26.

- The SpLD Assessment Standards Committee (SASC) is an advisory and regulatory body for practitioner assessors of Specific Learning Difficulties. SASC works in cooperation with key professional associations for SpLD practitioners including ADSHE (Association of Dyslexia Specialists in Higher Education), The BDA (British Dyslexia Association), The Dyslexia Guild, Helen Arkell Dyslexia Charity and Patoss (The Professional Association of Teachers of Students with Specific Learning Difficulties) along with other specialist organisations concerned with assessment and a wide range of SpLD matters. Members of SASC are committed to principles of good practice across all age ranges and throughout the profession.

Useful Resources

- Online training available from www.patoss-dyslexia.org:

- OnDemand: How English Words Really Work: An Introduction to Morphology

- OnDemand: Morph Mastery – An Introduction

- OnDemand: Morph Mastery in the Classroom

- OnDemand: Morph Mastery Information Workshop for Parents – How to Use Morphology at Home to Aid Your Child’s Learning

- OnDemand: Beneath the Surface of Words: What English Spelling Reveals and Why it Matters

- OnDemand: Structured Word Inquiry: Literacy Instruction that Makes Sense of English Spelling for Students of all Ages and Abilities

- Live event: Morph Mastery: Ten Practical Ways to Use Morphology in your Setting (19 March 2024).

- Making Sense of Spelling – Gina Cooke (YouTube video)

- Teaching for Neurodiversity (free resources)

- SASC SpLD Assessment Standards Committee

- https://www.highspeedtraining.co.uk/hub/signs-of-dyslexia-in-children/

References

Bowers, P., P Bowers Structured Word Inquiry: Literacy Instruction that Makes Sense of English Spelling for Students of all Ages and Abilities, presentation for Patoss 2022 Annual Conference. Available from www.patoss-dyslexia.org, archived courses (accessed 7 February 2024).

Education Endowment Foundation, Improving Literacy in Key Stage 2, Education Endowment Foundation, https://d2tic4wvo1iusb.cloudfront.net/production/eef-guidance-reports/literacy-ks2/EEF-Improving-literacy-in-key-stage-2-report-Second-edition.pdf?v=1706860902 (accessed 2-2-2024).

Levesque, K., Breadmore, H. and Deacon S. H. (2021) ‘How Morphology Impacts Reading and Spelling: Advancing the Role of Morphology in Models of Literacy Development’, Journal of Research in Reading, 44 (1), pp. 10–26.

SASC Response to the Green Paper 2022, https://www.sasc.org.uk/media/h3zjcxw3/sasc-reponse-to-send-green-paper-july-2022.pdf (accessed 2-2-2024).

Snowling, M. J. & Hulme, C. (2020). Annual Research Review: Reading Disorders Revisited – the Critical Importance of Oral Language. Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry, 62(5), 635–653.

Register for free

No Credit Card required

- Register for free

- Free TeachingTimes Report every month