The move brings back into painful focus the crisis of languages learning in Great Britain and Northern Ireland. It sheds a dim light on the government’s woeful lack of a national languages strategy. Its myopic reliance on the currency of English as a global language is widely disputed as a cogent strategy to expand ‘unfettered’ international trade with Europe and the rest of the world.

Because there are now twice as many people in the world who speak English as another language than native users of the language.

The reality is that native proficiency in English is no longer a global advantage.

Lost export revenues for British businesses: £46 billion?

However, despite the globalisation of English, a report commissioned for the UK Trade and Investment (UKTI) in 2006 calculated that the UK’s deficit in language skills and intercultural agility might be costing it 3.5% of its GDP, a colossal £46 billion per annum. This staggering amount completely dwarfs any sum that the UK might think it is saving in the short term by exiting the Erasmus+ Programme.

According to a UK Parliamentary All-Party Working Group reporting in 2019:

“SMEs (Small and Medium Enterprises) using languages report 43% higher export/turnover ratios. But over 80% of SMEs operate in English only, and the DIT’s (Department of Trade and Industry) Export Strategy doesn’t mention language skills….. The case for languages is compelling and urgent. The UK’s languages deficit is holding us back economically, socially and culturally.”

Erasmus+ benefits for the UK

Since its inception in 2014, Erasmus+ funding supported more than UK 4.700 projects and 128000 participants. It remains to be seen whether the £1 million pound replacement Turing Programme, named after the World War II code breaker, will live up to the Government’s promises. Even its target number of 35000 participants is well below the 54619 UK students, trainees, school pupils and teachers who took part in Erasmus+ in 2019.

While it is widely believed that Erasmus + was simply a university student exchange scheme, the programme also created thousands of opportunities for schools and post-16 FE’s to subsidise language, cultural and training projects with partner schools and colleges in other EU countries.

Erasmus+ was particularly valuable because it gave young people from disadvantaged backgrounds and those with special needs a real experience of international engagement. According to a House of Lords report, this is because it offered “unparalleled financial support and flexibility to enable people from lower income backgrounds, and those with medical needs or disabilities, to take part in educational exchanges.

Making language learning work for Britain

In their ‘Policy Briefing on Languages, Business, Trade and Innovation’, Wendy Ayres-Bennett and Janice Carruthers write:

“Enhanced language skills in the workforce would be a major benefit to UK business. All sectors represented echo the CBI’s comment in ‘Educating for the Modern World’ (2018): ‘To achieve the government’s ambition for a “Global Britain”, we have to get language teaching in our schools right’.

Whether they need more basic language skills in one or more languages, or a high level of linguistic and cultural fluency, UK businesses would be more productive and competitive if language skills were stronger. This applies at every level of fluency, from basic knowledge to near-native fluency.”

Primary Languages

In its 2020 edition of ‘Language Trends’ , the British Council whose role is to promote the UK’s trade and business interests overseas, catalogues the inequalities in access to high quality language teaching.

Its survey of primary schools where languages is a statutory part of the curriculum found that:

- “Over the past three years, the number of primary schools availing of opportunities for international engagement has steadily decreased. 61% of primary schools reported having no opportunities for international engagement for pupils or teachers,

- whether teaching is by class teachers, specialist speakers including some HLTAs or specialist languages teachers, over 70% of teachers have not accessed language-specific Continuing Professional Development (CPD) in the last year. Where the highest language qualification of school staff is a GCSE, the figure for those who have not availed of subject specific CPD increases to 86%.

- of the 167 primary schools which were inspected by Ofsted, just 7.7% reported that languages were a focus of the inspection (‘deep dive’)12 and/or were mentioned in the public report.”

Language Learning for children aged 11-14 – alarming decline

The ‘Language Trends’ survey laid bare evidence of the continuing demise of languages in UK secondary education, a decline which it shows is magnified in schools where there are high concentrations of pupils entitled to Free School Meals and Pupil Premium.

“Schools with fewer teaching hours for languages at KS3 are more likely to have higher proportions of pupils eligible for FSM and lower overall educational attainment. Schools in the lowest quintile for FSM eligibility are over twice as likely as those in the highest quintile to offer more than three hours of languages per week at KS3.”

‘Language Trends’ research by the British Council indicates that disadvantaged pupil groups, who tended to benefit from the EU Erasmus+ Programme, are exactly the populations of young people in the UK who have become the least likely to be offered an equal opportunity to learn a modern language in secondary school and benefit from international engagement.

“Schools with fewer teaching hours for languages at KS3 are more likely to have higher proportions of pupils eligible for FSM and lower overall educational attainment.”

EBacc and new Scottish exams fail to revive languages

The British Council’s findings reveal the Government’s failure to revive languages by making MFL or Classics one of the five pillars of the so-called ‘English Bacc’.

“Languages form one of the five pillars of the government’s English Baccalaureate (EBacc) measure of school performance alongside English, mathematics, the sciences, and the humanities (geography or history). The EBacc had a temporary effect on improving uptake of languages at General Certificate of Secondary Education (GCSE) in 2013; however, in 2017 only 38.2%7 of pupils in the state sector were entered for the EBacc, and of those who entered 4 out of the 5 components 80.4% were missing the languages component”

A 2019 BBC survey about modern languages trends in UK secondary schools had a response from 2048 mainstream schools shedding light on the gloomy picture around the country:

- In England: drops of between 30% and 50% since 2013 in the numbers taking GCSE language courses in the worst affected areas.

- In Wales figures showed that GCSE language entries fell by 29% over five years, and 35% of schools have dropped at least one language from their options at GCSE.

- In Northern Ireland, the numbers taking modern languages at GCSE have fallen by 40% since 2003, with 45% of schools saying they have cut the numbers of specialist language teachers in the past five years.

- In Scotland: since 2014 a 19% decline in language entries at National 4 and 5 level (GSCE equivalents) . 41% of schools who responded said they had stopped offering at least one foreign language course to 16-year-olds.There were also five council education departments in Scotland where no National 4 or 5 exams in German were recorded in 2017/18.

A Level entries fall for MFL

Given the parlous state of languages for the 5-16 age group, it is hardly surprising that the rot has spread to post-16 and university courses

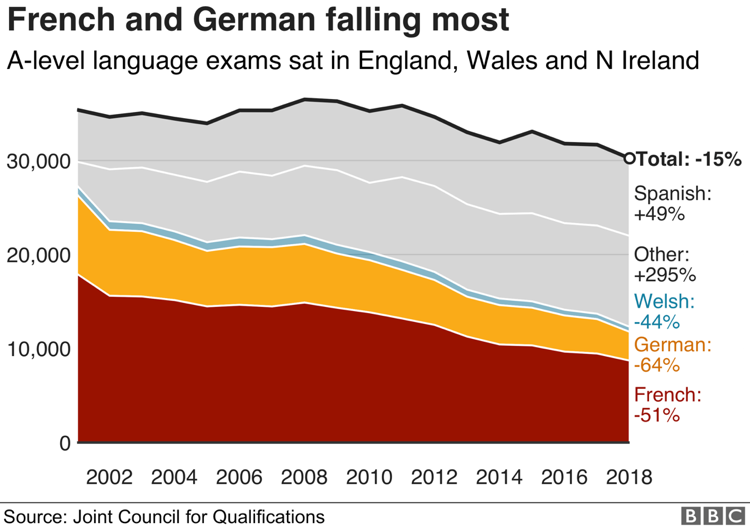

In OFQUAL’s 2019 analysis of “Recent trends in modern languages exam entries in anglophone countries”, its author, Darren Churchward, found that in the UK A Level entries in MFL had dropped by 20% in the period 2002-2019.

The BBC survey used figures from the Joint Council for Qualifications to illustrate this alarming downward trend.

However, interestingly, the same analysis shows that in the Republic of Ireland, an Anglophone country fully committed to the EU, the level of entries for Modern Languages in its A Level equivalent Leaving Certificate qualification increased over a 13-year period between 2005 and 2013. In contrast to England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland, this upward trend included an increase in the number of entries for German.

To enhance cooperation in education with Northern Ireland, the Republic of Ireland will pay and make it possible for any student holding a British passport and enrolled at a university in Northern Ireland to participate in the EU flagship Erasmus+ Programme.

University MFL courses disappearing

In their report for the British Academy entitled “Language learning: turning a crisis into an opportunity”, Neil Kenny and Harriet Barnes collated startling data showing:

“The number of students studying modern languages at undergraduate level has fallen by 54 per cent since 2007–08 …. In the same period, at least 10 university modern language departments have closed, and another nine have significantly downsized. Fewer than half the pupils in English secondary schools take a GCSE in a modern or ancient language. Half of sixth-form colleges in England have stopped offering at least one modern language A level. And can you guess how many secondary school pupils studied German A level in Wales in 2018? A mere 70.”

Call for Action

In 2016 the Teaching Schools Council produced an authoritative, review of pedagogy in Modern Languages under the leadership of Ian Bauckham CBE, recently appointed in December 2020 as interim head of OFQUAL. The review resulted in a compendium of good practice instructions in an attempt to shore up Modern Languages which Bauckham recognised was in a fragile state.

In November 2018, a Primary Languages Policy Summit (RIPL), assembled leading players in policy making as well leading primary languages practitioners and academics from across the country to produce the ‘White Paper Primary Languages Policy in England – The Way Forward’.

In March 2019, the ‘All-Party Parliamentary Group on Modern Languages produced its own recovery plan for languages.

In July 2020, The British Academy, the Arts and Humanities Research Council, the Association of School and College Leaders, the British Council and Universities UK joined forces to propose ‘Towards a national languages strategy: education and skills’

National Centre of Excellence for Languages

In August 2018, the DfE itself unveiled a “new drive to deliver a nation of confident linguists and ensure businesses have the skilled workers they need.”

A national Centre of Excellence was led again by Ian Bauckham CBE and supported by 9 regional hubs.

- Dartford Grammar School, Dartford

- Dixons Kings Academy, Bradford

- Presdales School, Ware, Hertfordshire

- Sir William Borlase’s Grammar School, Marlow

- St James’ School, Exeter

- The Broxbourne School, Broxbourne, Hertfordshire

- Archbishop Temple School, Preston

- Blatchington Mill School and Sixth Form, Hove

- Cardinal Hume Catholic School, Gateshead

Its mission is “to improve language curriculum design and pedagogy, leading to a higher take up and greater success at GCSE.”

In December 2018, the University of York was awarded the contract to run what is now known as the ‘National Centre for Excellence for Language Pedagogy (NCELP).

The nationwide impact of the National Centre of Excellence for Language Pedagogy is still to be assessed.

Broken Promise

Nick Gibb, Schools Minister for Standards since 2015, declared:

“It has never been more important for young people to learn a foreign language than now. An outward looking global nation needs a new generation of young people comfortable with the language and culture of our overseas trading partners”.

But these good words were long forgotten when the UK Cabinet of Ministers and Houses of Parliament agreed the Brexit trade deal depriving young people in England, Wales and Scotland access to the world beating Erasmus+ programme. Languages learning was expendable again and another Government promise was broken.

Teachingtimes

Teachingtimes stands ready with its professional learning platform to support the momentum of this huge effort to halt the decline of language learning in the UK. Articles illustrating best practice that can be successfully emulated across the country would be well received for publishing on our website.

References

All-Party Parliamentary Group on Modern Languages (2019) National Recovery Programme for Languages

Ayres-Bennett, W. and Carruthers, J. (2020) Policy Briefing on Languages, Business, Trade and Innovation

Churchward, D OFQUAL (2019) Recent trends in modern foreign language exam entries in anglophone countries

Collen, I. British Council (2020) Language Trends 2020

Confederation of British Industry (2018) Educating for the Modern World p23

Crystal, D. (1997). English as a Global Language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Crystal, D. English Today (2008) , Volume 24 , Issue 1 , pp. 3 – 6 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0266078408000023

Department for Education and Skills (2018) Languages boost to deliver skilled workforce for UK’s businesses

European Commission Erasmus+ in Numbers, UK Factsheet

Graddol, D. (1997). The future of English? A guide to forecasting the popularity of the English language in the 21st century.

Holmes, B. and Myles, F. (2019). White Paper: Primary Languages Policy in England – The Way Forward. RiPL: www.ripl.uk/policy/

James Foreman-Peck, J. and Wang, Y. (2013) The Costs to the UK of Language Deficiencies as a Barrier to UK Engagement in Exporting: A Report to UK Trade & Investment

Jeffreys, B British Broadcasting Corporation (2019) Language learning: German and French drop by half in UK schools

Kenny, N. and Barnes, K. The British Academy (2019) Language learning: turning a crisis into an opportunity

The National Centre for Excellence for Language Pedagogy (NCELP) https://ncelp.org/

Teaching Schools Council (2016) Modern Foreign Languages Pedagogy Review: A review of modern foreign languages teaching practice in key stage 3 and key stage 4

The British Academy, The Arts and Humanities Research Council, The Association of School and College Leaders, The British Council and Universities UK (2020) Towards a national languages strategy: education and skills

Simon Sharron was until 2019 headteacher in the network of multilingual European Schools after a successful career in school and modern languages leadership in the UK. He is now a commissioning editor for Teachingtimes.

Register for free

No Credit Card required

- Register for free

- Free TeachingTimes Report every month