Imagine the best teacher you have ever seen or worked with. What makes them so great? So special? Equally, imagine the best school leader you have ever seen or worked with. What makes them so effective? What would your school be like if every teacher and every leader was as good as those you are imagining? What would the children’s experiences be like in that school? Would every child, regardless of their background and learning needs, be flourishing academically, socially and emotionally? The thinking school is a learning organisation where all members of staff see themselves as both learners and leaders. They are all reflective, creative decision makers who understand that they are constantly developing and learning.

The Thinking School

In the thinking school, everyone is responsible for learning and teaching, and children’s learning outcomes are central to every conversation. I have deliberately used the term ‘thinking’ because I want to capture the self-reflection and criticality the word implies. When I walk into a classroom, I look to evaluate the quality of children’s thinking and engagement, as well as what may be produced on paper. I will also seek to evaluate the quality of teachers’ engagement, thinking and self-reflection. Teachers make thousands of decisions every day. I am interested in the quality of self-reflection and evidence-based thinking that directly informs their decision making. I want to enable teachers to have opportunities to develop an explicit understanding of the tacit knowledge that informs their decision making.

In this article, I discuss my own experiences of developing what I have called ‘The Thinking School’. I began my first headship in September 2012, at the primary school I attended as a child. Six weeks prior to me commencing my post, the school was deemed to be ‘Requiring Improvement’ by Ofsted. Its results in 2011 had placed it in the lowest 10 per cent of schools nationally for pupil progress—much work to be done! If the Ofsted judgement had come prior to my interview, my lack of experience would likely have seen me not even shortlisted, let alone appointed.

When I arrived at the school, the staff team were on their knees. The working environment did not support collaborative learning among the teachers and this was something I wanted to tap into. My doctoral research demonstrated that the greatest influence on the quality of children’s learning is the quality of teaching. And I believe that the greatest influence on the quality of teaching is the quality of teacher learning. By improving teacher learning, I would impact positively on children’s learning, and this was key to retaining my job. I knew that Ofsted would return within eighteen months and if the school could not demonstrate significant and sustained improvement, I would be vulnerable.

Morale was low at the school. Experienced teachers did not have the time to support less experienced teachers because they themselves felt under pressure and judged on the progress of their own thirty children. Low pupil outcomes across the school and an imminent Ofsted inspection meant that teachers did not feel they had the time to focus on anything other than their own classrooms—leaders were focused on telling colleagues what to do in a culture of hierarchy and compliance. I had to develop the learning culture for adults at the school.

Consider the extent to which the learning environment in your school:

- provides opportunities for collaborative working

- is genuinely mutually supportive

- supports opportunities to work in different groups

The value of distributed leadership

One of the first things I did was to move away from a hierarchical model of leadership to a more distributed one. Every member of staff within the thinking school should see themselves as a leader. This is because when you lead, you have to think wider and bring your brain to work. You have to be aware of the impact of your actions upon others, and you are aware of a wider responsibility to the institution. Once we develop a core sense of shared values and understand our collective responsibilities, we all become capable of making leadership decisions in relation to the institution.

Leadership is also related to learning and growth. The more we have opportunities to lead, the more we learn about ourselves, our colleagues and our school, and it supports our growth as leaders of learning. I hear school leaders describe how they have distributed leadership in their schools. However, often this just involves delegating jobs and titles, for example subject leaders. I question the extent to which these middle leader roles are more likely to involve managing rather than leading. If we are all doing our jobs effectively, an NQT is able to make leadership decisions that reflect the ethos of the school.

Building a dynamic learning community

My research sought to identify the complex factors that influence teachers’ learning experiences in primary schools. I evaluated teachers’ perceptions of these factors and drew on them to build a model for the provision of positive formal and informal learning for teachers in primary schools. This article is an introduction to how you can develop this model within your own schools.

Key features of this model include specific teacher learning activities that can be implemented in schools to support formal learning opportunities and encourage informal learning activities within the wider development of a positive and expansive learning environment.

Examples of these activities include:

- opportunities and time made available for teachers to conduct research.

- opportunities for teachers to select own focus for professional learning that is related to pupil learning and contextualised in their own practice.

- opportunities to coach and be coached.

- opportunities for collaborative working in pairs and teams across different groups within the school.

- opportunities to engage in peer learning and lesson studies to co-construct knowledge.

- non-judgemental, learning-focused lesson observations.

To enable this model to work successfully, it is imperative that teacher learning is led by learning-focused leaders who are able to work in partnership with teachers and contribute to the learning activities. Learning-focused leaders are so called because they judge the quality of their leadership in terms of their impact on children’s and staff learning. Through teacher engagement in a dynamic community of learners, they in turn develop the skills of learning-focused leaders. The community itself then continues to innovate, grow and develop. I describe the learning community in the model as dynamic because my work has shown that the development of these key learning activities has a dynamic effect on teacher learning in schools. The structures within the model create a culture within the school that in turn promotes the development of positive attitudes to learning.

All members of staff will become and develop the skills of learning-focused leaders. The word dynamic has been used to define both the system within the learning community that are ‘characterised by constant change and progress’ and the learning-focused leaders who are ‘positive in attitude and full of energy and new ideas’. I have designed a model that I hope will inform the future implementation of teacher learning activities in primary schools, and promote expansive, personalised formal and informal learning activities. I am passionate in my belief that if you implement this model, you will see a significant positive impact on the learning of all the children in your school.

Key features of the dynamic learning community

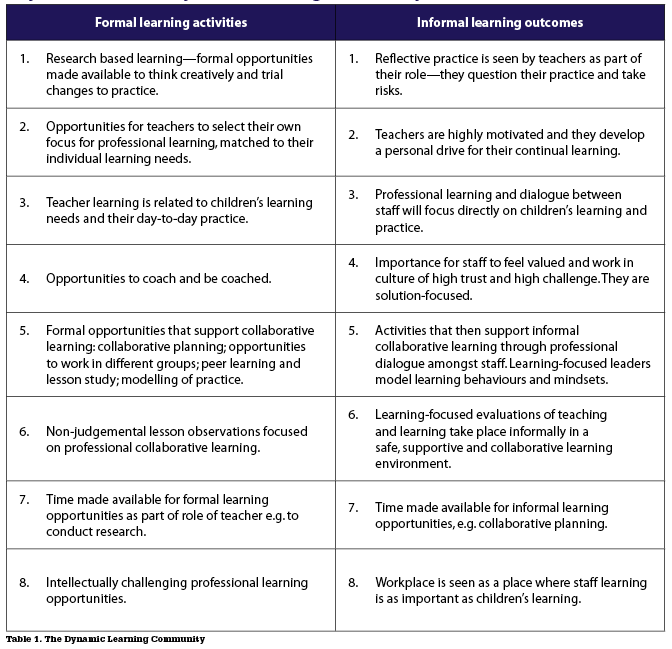

In Table 1, I have charted the key factors that the findings from my research and practice suggest will support teacher professional learning. In the thinking school, I am arguing that through the effective implementation of the eight formal learning activities, there will be an associated dynamic effect in supporting the development of informal learning across the school. These informal learning activities will then impact upon teachers’ attitudes to their own and others’ learning within the school.

A consistent implementation of these activities will ensure that the learning environment supports the development of teacher learning through formal and informal workplace learning activities. These activities will

have a positive impact on teacher wellbeing and individual dispositions to learning and in turn support the development of learning-focused leaders. The central premise of the thinking school is that we are developing a community of learners who are evaluating their practice in an ongoing cycle of improvement. I am not saying that schools cannot be successful if they don’t work in the ways that I’ve described. I’m arguing that by becoming a thinking school, they can become even more successful.

Research-based practice … Reflective practitioners

In the thinking school, all teachers are engaged in research; sometimes individually, but mostly collaboratively. They investigate their own and each other’s practice in the quest for continual improvement. The learning environment encourages engagement in research, and provides resources for teachers to undertake it effectively. Teachers can access research from across the world that promotes thinking and reflection upon practice. Strong partnerships with leading universities ensure that as teachers begin to specialise in their research, they can access researchers and tutors who develop their thinking.

Teacher choice in learning … Personal drive to learn

When teachers engage in learning activities they don’t see as personally relevant to their own learning needs, they seldom persevere. For example, Early Years practitioners are often left exasperated with having to sit through training sessions that are more appropriate for Key Stage 2 teachers. What came through clearly from the research was that teachers were more motivated to engage in their learning when they were given some choice in what they learned about. This depended on the relevance to their present job and also where they were in their own professional development. Teachers want to have a voice and to drive their own learning.

Action research enables teachers to identify the topics they want to explore and the key research questions to focus on. Critics may argue that too much teacher choice will result in incoherence and lack of focus. I think it will do the opposite, as long as you ensure that all of our collective work is focused on improving children’s learning outcomes. Remember that we want our teachers to bring their brains to work. It is the difference between a learner being told a theory, and discovering that theory for themselves. We are more likely to retain learning if we have been able to discover it for ourselves.

Learning related to children … Staff focus on children’s learning

The teachers’ passion and energies for their professional learning are directed at their children’s learning. Unfortunately, I have seen too many generic professional learning activities that either aren’t personalised to individual teachers, or aren’t sufficiently related to children’s learning needs. My research found that the teachers were motivated to engage in professional learning that directly related to their current practice. Every class is different, so our analysis should be focused on practice and the individual learning needs of the children in the class and how to help them learn and develop.

Coaching … High challenge and high trust.

The opportunity to be coached has been a fantastic professional learning opportunity for me. I believe that every member of staff at the thinking school should be trained in coaching, and should have the opportunity to coach and be coached regularly.

Teachers who have developed coaching skills and expertise put them to good use in informal interactions with colleagues. Team leaders and learning leaders (phase leaders) at my school are expected to participate in coaching sessions once a fortnight and to use their coaching skills to develop their team.

Formal collaborative learning … Informal collaborative learning.

By designing as many formal opportunities as possible for collaborative learning, we create a culture in the school that promotes informal collaborative learning opportunities. It is essential therefore that teachers engage in collaborative learning beyond their own year group and across the school. Put simply, the more opportunities we have to work with our colleagues, the more likely we are to build a relationship with that person—we are then more likely to speak to them informally for instruction or advice.

When we first enabled teachers to engage in formal collaborative learning, we focused on year-group teams. This was easier because in one sense, the team was already established. It was also more straightforward to plan for these opportunities. As the learning community has grown and developed, we actively begun to go beyond year group teams. This engagement in learning with a wider range of people encourages teachers to engage in informal collaborative learning and professional dialogue across the school. This is fundamental in the development of the dynamic learning community and the building of trust across the school.

Time for formal learning … Time for informal learning.

During my research, I found that there was a resonance among teachers about perceived frustrations regarding their professional learning experiences. Time was a recurring theme. Firstly, teachers felt that they were already overworked and committed to regular additional hours of work both at school and at home. So even if they were motivated to engage in professional learning, they felt they didn’t have the time and energy to do so. For example, teachers were reluctant to engage in research because they didn’t see where they were going to find the time to do it. Many professional learning activities were seen by teachers to be imposing unnecessary additional duties in a very crowded and heavy working week.

Non-judgemental learning evaluations … Learning evaluations that are informal and trusting.

There remains too great a focus in schools on lesson observations that are used to judge teachers. Once a practitioner knows that they are being observed for such a purpose, they play safe and avoid risks, so it has little value as a learning experience.

School leaders have to evaluate and provide evidence of the impact of teachers on children’s learning but to do so requires far more than a single lesson observation. To evaluate the quality of our teachers in impacting upon our children’s learning, we draw upon a range of evidence and we include this evidence in teacher profiles that we have created.

Some of these profiles contain more than six years of evidence, including: evaluations of teaching, pupil progress data, parent voice, pupil voice, learning walks, evidence in books, masters assignments, teacher reflections and evaluations of planning. This range of evidence is used to inform appraisals and to validate our teachers’ successes and document the development in their professional learning and impact on children.

Intellectually challenging learning opportunities … Teachers value learning.

We want all our children to be intellectually creative and curious, with a passion and thirst for continual lifelong learning—and should want our teachers to develop in the same way. The aim of the thinking school is to create an expansive learning environment in which all members of the dynamic learning community see themselves as learners. Whether it’s children or adults, the learning activities we present them with need to be intellectually challenging. Activities that are too easy or too hard are inherently demotivating. We need learning activities that start from where the learner is at, and which then challenge their thinking to move them on.

During my research, teachers discussed the perceived value of learning activities that were personalised to their learning but also intellectually challenging. They felt they had done many of the activities before, or that they weren’t relevant to them, or weren’t intellectually challenging or presented new theories and ideas.

So what?

So, what has been the impact of developing these activities with our staff team at the centre of our thinking school? We have a confident, empowered team of teachers who are making a fantastic positive difference to our children.

Other key achievements at the school:

- In each of the past five years, the school has been placed at least in the top 10 per cent of schools nationally for pupil progress.

- Outcomes in each Key Stage are consistently above the National average.

- Fifteen teachers at the school have completed their Masters degree.

- The school has been recognised by the Mayor of London as a ‘School for Success’ for three consecutive years, one of only 34 primary or secondary schools across London.

- The recruitment, retention and advertising budget in the past seven years has been £28.

In March 2019, those teachers who had been told they were ‘Unsatisfactory’ or ‘Requiring Improvement’ were told by Ofsted they were ‘Outstanding’. Ofsted graded our school as Outstanding in all aspects—although we don’t work in the way we do for Ofsted, we know how important that judgement is for our local community. In September 2018, I was appointed Executive Head Teacher at another local school—a school in which two head teachers had resigned in the previous year and the entire Governing Body had resigned en masse. I took the opportunity to implement the strategies detailed in this article in the second school. When Ofsted came knocking at the second school, they too left confident in my methods and graded the school Outstanding in all areas.

My final line in the book The Thinking School details my ambition to consider how we can move from a ‘thinking school’ to a ‘thinking schools system’.

Kulvarn Atwal is a Headteacher and author of The Thinking School: Developing a Dynamic Learning Community.

Register for free

No Credit Card required

- Register for free

- Free TeachingTimes Report every month