Global AND Local!

The world of education is and should be a constantly evolving endeavor of discovery, experimentation, application, collegiality and reflection. This evolution means that over the last three decades education has been ‘strongly affixed to global norms and rules about what education is and how schools should operate’.i

As such, in a growing number of education systems the globalization of education has ensued, whereby reforms in curriculum, pedagogy and assessment have occurred to appease national mandates to become more globally competitive.ii Yet globalization as an outcome, especially within education, remains a contentious issue. This article presents discussion that responds to this contention through exploration of the concept of glocalisation as a means to promote both the global and local in the education of our young people. The development of an education leader’s glocal literacy will be discussed, along with the actions of an education leader to glocalise her learning community, as well as macro/meso/micro level examples of glocalisation within a school.

Globalisation of education

Preparing for uncertainty- Globalisation is the notion that the trends of the last half century have created a world in which people - our governing institutions, cultures and markets - are increasingly interconnected.

Cifuentes-Goodbody, 2018iii

Globalization manifests in ‘the movement of ideas across local contexts’.iv As the world becomes smaller through increased investment in, access to, and reliance on technology to inform and enhance our daily lives, the education sector is not immune to the effects of this movement. Nor should it be. The perceived benefits of globalizing our schools and the curricula and pedagogies utilized within, stems from a desire to prepare our young people to be agile in response to uncertainty, to expand their vocational potential and to empower them to recognize the opportunities that lie within diversity. As stated by Sanderson:

‘Education… needs to equip us better for life and work in a world where the dynamic associated with traditional national borders, whilst still a powerful agent of separation and regulation, is itself subject to change. This is particularly so with reference to the cross-border flows of culture, people and ideas.’v

Any resistance to a world that is coming together, as Reimer writes, ‘will exacerbate tensions, and cause us to miss many opportunities to collaborate along lines of difference in improving the world.’vi As such, a growing number of education systems around the world now act as mediums for globalization and as incubators of its agents.vii Furthermore, from an education policy perspective, globalization has strengthened the influence of international organisations such as UN, World Bank and OECD and their shaping and constraining of a country’s education policy options.viii

For example, the incorporation by the OECD of the Global Competencies measurement in their 2018 PISA test cycle brings with it an expectation for member states to conform and to develop their domestic education policies accordingly.ix As educators, we have a responsibility to make sure our young people understand their lives are shaped by globalization, yet the advent of globalization also heightens the risk of our education systems becoming more homogenized. This shift to a more homogenized education sector creates a glocal-local tension that sits squarely in the purview of education system leaders.

The global-local tension

For some, the interpretation of globalisation as the action of putting global standardisation or harmonisation ahead of local customs and practices, translates to fears around the erasing of cultural identities and celebrated differencesx. Globalisation has also been viewed as a simultaneous for both integration and segregation, whereby the integration of world cultures and the greater movement of individuals is in tension with those who benefit from such outcomes and those who are marginalized because of them.xi In response, a number of education policy makers, academics and practitioners believe that a correction towards the glocalisation of education is preferable. As Chiang writes:

‘We need to think globally and act locally in order to reconstruct the world into a global society that can help reduce the gap between globality and locality. Glocalization, thus, embraces the characters of cultural interaction and indigenization.’xii

The glocal perspective

A glocal perspective means being interdependent and interconnected and involves the fusion of ideas rather than blind imitation of global trends and marketsxiii. Having a glocal perspective also leads to the development of a glocal identity. Underpinned by a harmonious mix of global and local values, an individual’s glocal identity is strengthened via access to glocal spaces that serve to enhance cultural efficacies, creativity, and diversity of thought.xiv As leaders in education, we need to be mindful of how we promote a glocal perspective in our schools so that our staff and pupils feel informed, prepared and inspired to think and act with purpose in response to global-local tensions. Ironically, the global pandemic has put a spotlight on this tension through the contraction of our immediate worlds.

For many, the act of being homebound, during the pandemic, manifested into a heightened awareness of locality. As a result, more of us began to ask ourselves; Where is my food coming from? How can I maintain my relationships? What is the role that social media is playing in how I access information? Why can’t I feel relaxed? How can I exercise? Who is responsible for my child’s learning? The asking of such questions reflects the process of micro-globalisation or the shift in awareness from something more global to something more local.

So, how do we, as leaders in education, build on this recent shift in awareness but at the same time continue to prepare our pupils to be capable and effective global citizens whilst maintaining institutional compliance, competitiveness and relevance in an evolving education market? Developing a leader’s glocal literacy is a start.

Developing a leader’s glocal literacy

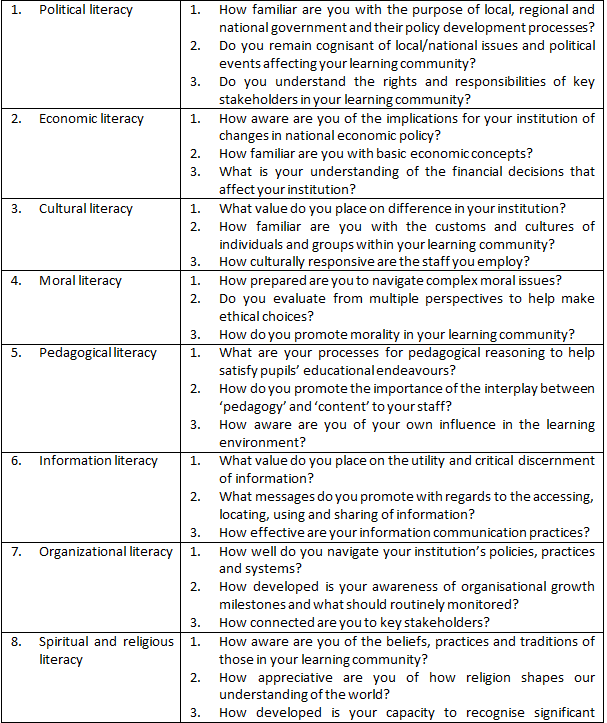

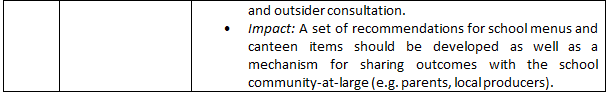

Brooks & Normone suggest that contemporary leaders in education should develop glocal literacy in nine specific knowledge domains: political literacy, economic literacy, cultural literacy, moral literacy, pedagogical literacy, information literacy, organizational literacy, spiritual and religious literacy, and temporal literacy.xv By their own admission, this list of knowledge domains was selective rather than exhaustive. As such, with the rise of the concept of relational leadership and its use to explore the quality of an educational setting and the social networks within, xvi relationship literacy has been added as a tenth knowledge domain to be developed. Social literacy has also been added in recognition of not just the continued challenges we face as an evolving society but because that evolution perpetually fuels the marginalisation of peoples and the stunting of their social mobility.

Table 1 provides a list of 11 knowledge domains relating to glocal literacy, each accompanied by three questions for leaders in education to consider as a means to develop their glocal literacy.

Table 1: Glocal literacy knowledge domains adapted from Brooks & Normone (2010) with accompanying development questions

Actions as a leader to glocalise your learning community

As part of any glocal literacy development commitment, it is important for leaders in education to see how fellow leaders have embraced the philosophies and practices of glocalism in their education institutions. Nirmeen Alireza is Academy Director and Founder of Nün Academy in Jeddah, KSA, which is part of the KED global network of schools. Her views on the importance of a Glocal Approach to learning are prominently displayed on the Nün Academy webpage (www.nunacademy.com):

We recognize the importance of educating our learners for life in a global village where international understanding is a key skill. To this end we endeavor to forge links with a wide range of people, groups and organizations from a diverse array of countries within the KED network and beyond.

Furthermore, through the offering of an international curriculum, bilingual education and a personalised learning approach, Nün Academy supports the glocally-orientated view that:

Today’s students study, live and work in a globalized world. Regardless of what education or profession they choose, they will collaborate and work with people and ideas from other countries, cultures and languages. The quality of their education and skills must be competitive and comply with the best international standards. That is a fact. But this fact does not necessarily mean giving up your own language and heritage. On the contrary, the more globalized the world becomes, the more important it is to also preserve a strong knowledge of and anchorage in your own language and culture.

When asked about her actions as a leader in promoting the local-global identity of her students, Nirmeen was adamant in her response that a glocal learning community was all about preserving identity:

“Students need exposure to globalization, but not at the expense of a local grounding and the identity development that comes of it. I’ve experienced international schools for a long time and seen how quickly students became disconnected from their mother tongue, from their heritage, from their culture. It happens within a generation. International schools can be like islands of excellence within countries, but struggle with local impact. In Saudi Arabia people want their children to learn English but I think they are less aware of what that means in terms of a loss of grounding in their own culture, in their own language and a loss of impact in their own community. You want the best of East and West but you don’t want the West at the expense of the East. For me it’s a matter of preserving identity but also having that impact on your community.”

For Nirmeen, liaising with stakeholders to find the right balance of learning environments to promote students’ glocal identities was often the most challenging part of her leadership.

“We’re constantly having to tweak the model, to find that balance between what the community wants, what the ministry dictates and obviously what we think is beneficial for our students. We have Arabic as the main language of instruction up to Year 3 to ensure they have a strong grounding in their mother tongue before they start to use English as their main language of instruction. We follow an international curriculum (CIE) and make it culturally relevant through use of examples from our own environment …. We also use our assemblies to discuss global values from an Islamic perspective. It is easy to assume these global values are rooted in the West but they are also rooted in our own traditions. It is important to discuss this connection to their own traditions so they don’t just end up seeing the East from a Western perspective but see the West from an Eastern perspective so to speak.”

When asked about the development of specific skills she attributes to students having a glocal identity, Nireem said it was all about the opportunities provided to students:

“It’s all about providing opportunities in the classroom and across the school. It’s about creating that sense of community through the discussion of values, it’s about exposing students to processes around conflict resolution, setting up classroom meetings, developing skills around how you listen to peoples voices, how you create agendas to problem solve, bringing local and global problems to the classroom and brainstorming solutions then trying them out and discussing them further. It’s about developing those skills that we think are essential for any citizen, to be able to communicate and deal with others both in their community and outside it.”

At Nün, developing teachers to think/act/teach with a glocal perspective was of paramount importance. As such, Nirmeen spoke about her prioritisation of recruiting the right people:

“When we conduct staff interviews we really focus on our values and why Nün was set up. We are looking for very particular outcomes for our students – that they are grounded, connected globally, but rooted locally. And when you interview people you get a sense whether that really resonates with them or not. We ask questions about their own learning experiences, their own teaching experiences, the importance of being strongly rooted in their own identity. As part of their training during induction, we focus on developing their understanding of cultural perspective, the cultural map, and getting them exposed to the local culture. We employ an expat community of Arabic and English speaking teachers along with local teachers. This means there is a lot of co-teaching as we are conscious that we do not want an Arabic part of the school and an English part of the school. We want to create glocal citizens so we want students to embody the best of both.”

Embedding a glocal perspective across pupils’ learning experiences

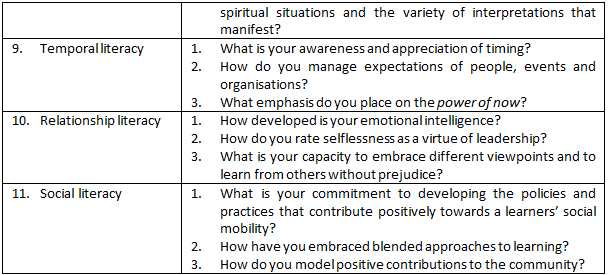

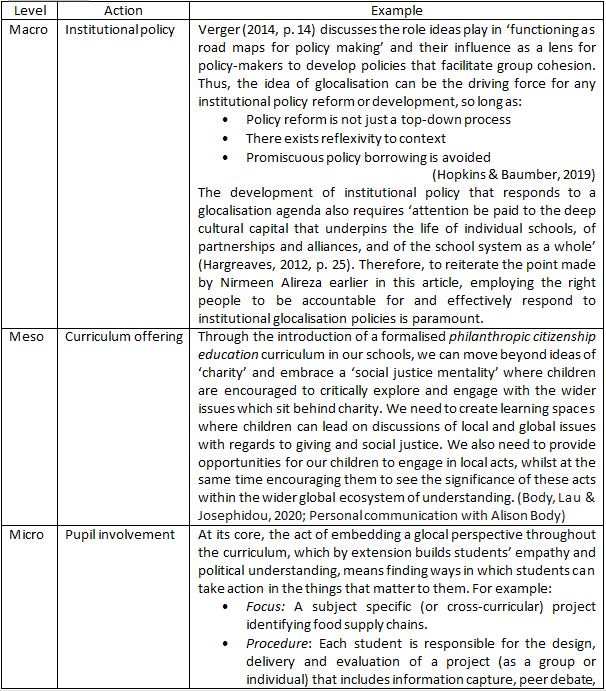

Further justification for the development of an education leaders’ glocal literacy relates to the view that ‘it is quite possible educational leaders are unprepared to confront the realities of leading schools in a global society’.xvii This unpreparedness has a flow on effect within an institution that translates into learning experiences that are ill-equipped to satisfy pupils’ global-local learning needs. So as a leader in education it is important to expand one’s thinking beyond any ‘one-and-done’ notion of glocalism (e.g. ‘We offer our pupils the chance to go to France for the weekend for their Yr 9 Geography studies’ [glocalism box ticked!]) and to consider a more strategic and whole school approach that facilitates a collective institutional embracing of glocal responsibility and along with it the development of individual glocal identity. Examples of how this might be achieved at the macro, meso and micro levels within a school can be found in Table 2.

Table 2: Macro, meso and micro level examples of a learning institution’s commitment to glocalisation

Final thought – the importance of connection

For some leaders in education, the realities of glocalisation can already be seen in the day-to-day learning experiences of its staff and pupils. For others, the very idea of glocalisation may represent ‘an agenda too far’ in an already saturated educational mission. Whichever situation applies, it is important for leaders in education to consider the following challenge:

‘All organizations, especially education systems, are of this world, not separate from it. To earn their legitimacy, they need to be connected with the communities, countries, and world they serve… The expansive needs of our community and the world should guide us as we strive to serve.’xviii

Dr. Kendall Jarrett is Lecturer in Academic Practice, University of Kent (UK)

References

- i Baker, D. P., & LeTendre, G. K. (2005). National differences, global similarities: World culture and the future of schooling. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- ii Hajisoteriou, C. & Angelides, P. (2020). Examining the nexus of globalisation and intercultural education: theorising the macro-micro integration process. Globalisation, Societies and Education, 18(2), 149-166. DOI: 10.1080/14767724.2019.1693350

- iii Cifuentes-Goodbody, N. (2018). Culture and translation in the rise of globalised education. In Sue-Ann Harding, Ovidi Carbondell Cortés (eds) The Routledge Handbook of Translation and Culture Routledge (pp. 591-610). https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/doi/10.4324/9781315670898-33

- iv Paine, L., Aydarova, E. & Syahri, I (2017). Globalization and Teacher Education. In: Clandinin, J. & Husu, J. (eds). Handbook of Research on Teacher Education, (pp. 1133-1148). London: Sage.

- v Sanderson, G. (2004). Existentialism, globalisation and the cultural other. International Education Journal, 4 (4), 1 – 20.

- vi Reimers, F. (2016). Wrapping out minds around the world: Countries must teach their students to be stewards of inclusive and sustainable development. US News and World Report. Available at: https://www.usnews.com/news/best-countries/articles/2016-08-12/education-must-focus-on-globalization

- vii Marginson, S. (1999). After globalization: Emerging politics of education. Journal of Education Policy, 14(1), 19-31.

- viii Al’Abri, K. (2011). The Impact of Globalization on Education Policy of Developing Countries: Oman as an Example. Literacy Information and Computer Education Journal, 2(4), 491-502.

- ix Dvir, Y., Maxwell, C., & Yemini, M. (2019). ‘Glocalisation’ doctrine in the Israeli Public Education System: A contextual analysis of a policy-making process. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 27(124), 1-21. DOI: 10.14507/epaa.27.4274

- x Sumi, A. (5th February 2020). Glocalization: a happy blending of globalization and localization. Available at: https://english-meiji.net/articles/48/

- xi Sahlberg, P. (2004). Teaching and globalisation. Managing Global Transitions. 2(1), 65-83. Sanderson, G. (2004). Existentialism, globalisation and the cultural other. International Education Journal, 4 (4), 1 – 20.

- xii Chiang, T-H. (2020). Is Cultural Localization Education Necessary in Epoch of Globalization? An Analysis of the Nature of State Sovereignty. In G. Fan & T. S. Popkewitz (eds.), Handbook of Education Policy Studies: Values, governance, globalization and methodology (vol. 1) (pp.329-341) Singapore: Springer Open. DOI: 10.1007/978-981-13-8347-2_15

- xiii Khondker, H. (2005). Globalisation to Glocalisation: A Conceptual Exploration. Intellectual Discourses, 13(2), 181-199.

- xiv Dvir, Y., Maxwell, C., & Yemini, M. (2019). ‘Glocalisation’ doctrine in the Israeli Public Education System: A contextual analysis of a policy-making process. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 27(124), 1-21. DOI: 10.14507/epaa.27.4274 Iwuohaa, V., Ezeibeb, E. & Ezeibe, C. (2020). Glocalization of COVID-19 responses and management of the pandemic in Africa. Local Environment. 25(8), 641-647.

- xv Brooks, J. & Normone, A. (2010). Educational Leadership and Globalization: Literacy for a Glocal Perspective. Educational Policy. 24(1), 52 –82 xvi Smit, B. & Scherman, V. (2016). A case for relational leadership and an ethics of care for counteracting bullying at schools. South African Journal of Education, 36(4), 1-9. DOI: 10.15700/saje.v36n4a1312

- xvii Brooks, J. & Normone, A. (2010). Educational Leadership and Globalization: Literacy for a Glocal Perspective. Educational Policy. 24(1), 52 –82.

- xviii Marx, G. T. (2006). Using trend data to create a successful future for our students, our schools, and our communities. ERS Spectrum. 24(1), 4-8.