Uncertainty now stalks the world. To meet the challenges it presents, in a manner that supports human resilience, equality, health and well-being, we must shift how we think about the nature of education. We need to reconsider who learning is for and how it positions learners to deal with a future where little is certain, except for the need to become effective lifelong learners, in order to respond to the current and future challenges of a complex world.

While the challenges of our time can be daunting, there are rich resources to draw upon in rethinking what is possible in developing human capacity to engage with these challenges and how we think about the nature of learning. Over the past few decades, findings from cognitive, neuro- and learning sciences have amassed to inform a powerful new vision of what learners are capable of – what human potential really looks like.

This introduction to the vision that we refer to as Next Level Learning (NLL). It draws upon the extant research to put forth a synergistic set of concepts that together promise to change how learners and learning in both K-12 education and workforce development is conceptualized. It is followed by a series of articles that consider each of its main features at a deeper level and then dive into specific actions that educators can take to actualize NLL in the lives of students.

Many would agree that we need a different way to position learning in contrast to the traditional, highly structured, and didactic forms of education that we have been operating under, in which learners are expected to behave as passive and sponge-like – merely absorbing the information they are taught.

However, Next Level Learning looks beyond what would currently be viewed as best practices – learners who are attentive, engaged, and focused on building and applying understanding through projects and other hands-on assignments. These best practices are positive, but they are not enough. To effectively meet the challenges of a complex world, we truly need to take learning to the next level and to support the next generation in becoming expert learners.

What Key Shifts Does Next Level Learning Involve?

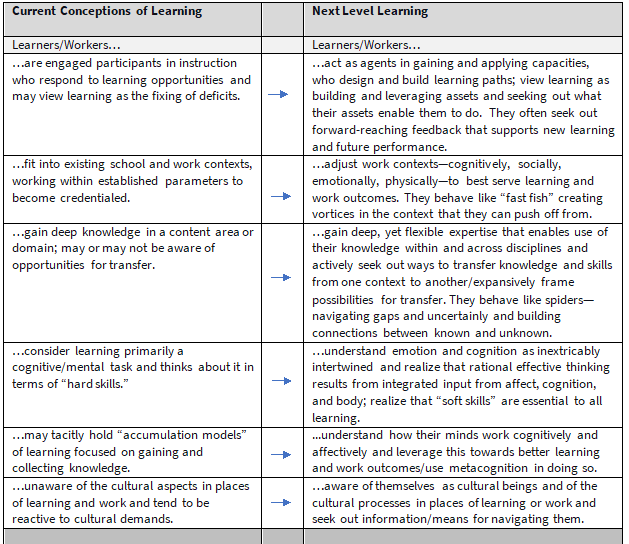

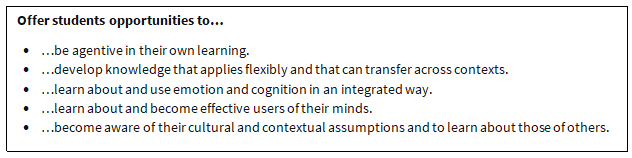

Next Level Learning sets forth five key shifts in how learners engage in the learning process. As summarized in the chart below, Next Level Learners are: 1) agentive in their own learning and in actively adjusting the contexts around them, emotionally, socially, physically, and cognitively, to support their best learning and performance outcomes; 2) focused more on developing flexible expertise that they can apply and transfer across contexts than on classical, and often isolated, deep understanding; 3) integrated emotional and cognitive beings with embodied minds which allows them to bring their whole selves to learning and performance; 4) informed and effective users of their own minds in that they regularly seek out information about how embodied minds work and leverage this information forward in learning and performance; and 5) cultural beings who reflect upon their own cultural and contextual assumptions, seek to be aware of those of others and consider how to navigate between and across cultural contexts.

In the paragraphs to follow, we introduce each feature of Next Level Learning, its implications, and why it is important for understanding in a complex and uncertain world.

1. Next Level Learners are agentive.

A key characteristic of Next Level Learners is that they are agentive in their learning and work performance. They don’t wait for learning to come to them; they actively seek it out and pursue ways to find out new information, figure out how to solve problems and challenges, and develop new skills that support future learning. They go beyond being engaged in instruction that might be planned by others. Instead they set goals and develop learning paths towards new understandings and abilities.

These goals often build upon their interests, curiosities, and passions. They build skills that support their “finding out” capacity. They tend to gain knowledge not just for the sake of having it but for the goal of being able to do something with it. Instead of learning something and then asking the question, “how do I apply this learning?”, they gain information in service of what they want to be able to do—such as coding or achieving a certain contrast in a work of art, for examples.

Terms such as “agentive” and “learner-centered” are increasingly common in discourse about education. In what ways is “agentive” as intended in NLL similar to and different from these uses? Agentive is sometimes used to refer to self-determination of what one is trying to achieve and develop mastery of. This is the sense of agentive referred to in pedagogical approaches such as Living Curriculum1 in which learners pursue interests and develop learning paths for a significant portion of their school experience.2

This can lead to powerful learning and significant knowledge about how to learn. Agentive approaches, as intended in NLL, includes these forms of mastery-orientation and Living Curriculum as some of the purest forms of agentive learning, but it is not limited to them. It also acknowledges that some learning is in service of broader goals that school or work requires.

For example, agentive learners who want to take advantage of an opportunity in a makerspace lab would include in their goals taking the required safety course that enables access to the lab. A caveat here is, that to be deemed agentive in these instances, learners must understand the relevance of the goals or requirements towards their broader goals such that the requirements are contextualized.

“Learner-centered education” is another term that is commonly heard in educational discourse. It is used to refer to focusing on students’ needs, recognising their individuality, helping students to meet their potential, and/or offering experiential learning.3 Yet, learners are commonly recipients of learning experiences that educators design in service of their development. While these uses are not at odds with NLL, the use of learner agency in NLL is intended to convey that the learner is at locus of control for their learning.

Agentive learners are proactive about their own learning, but they are also agentive about the contexts of their learning. Scientists, studying how fish swim as fast as they do, found that fish create vortices in the water that they push off from to enable their performance.4 Agentive learners behave like fast fish. They actively modify their contexts in cognitive, social, emotional, and physical domains to learn and perform at their highest level.

This means they might do things such as ask for information in multiple representations, step away in order to absorb information to which they have a negative emotional reaction, ask other students or colleagues to help them manage both social and solo time so they can do their best work when they are most alert and can benefit from collaborative exchanges when they are most socially inclined, or rearrange the space in which they are working in order to help them concentrate.

While being agentive is a clear asset for learning and performance, agentive learners sometimes push hard on their teachers in instructional contexts. Therefore, it is important that the educational environment values and embraces their proactivity and the benefits derived from adjusting the contexts around them.

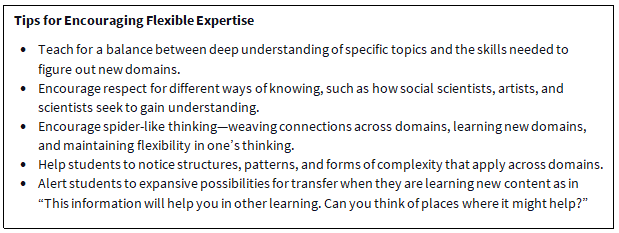

2. Next Level Learners focus on developing flexible expertise.

Deep understanding and expertise have been considered the holy grail of effective education over the past few decades. While deep understanding can be critical for launching innovation and for contributing to collaboration across disciplines, research shows that the ability to learn and work across domains—what is referred to as adaptive expertise—is critical for solving problems in a complex and uncertain world.

The value of classical expertise and deep understanding is that one gets to know the nuances of a domain well and can recognize patterns and features when working in problem spaces relevant to one’s expertise. However, research shows that the very processes of automatization and chunking of concepts that support deep expertise can also lead to rigidity in thinking.5

This underscores the importance of cultivating adaptive or flexible expertise in addition to classical expertise. A creative and flexible focus across domains invites broadened connection-making and application. Adaptive expertise involves spider-like thinking—weaving connections across domains, learning new domains, and maintaining flexibility in one’s thinking. This can matter most in times of uncertainty and in changing terrain. One needs to be able to work at the edge of one’s competence and build flexibly from what is known to make connections to both solid and tentative or uncertain contexts.

Becoming an adaptive expert requires understanding structures, patterns, and forms of complexity that apply across domains.6 It also invites a stronger and more expansive focus on transfer as one looks across contexts for application opportunities.7 In order to note these opportunities, one must detect or be sensitive to occasions for applying knowledge and abilities, must have the requisite ability to engage in transfer, and must be inclined to follow through. This is referred to as a dispositional stance on thinking and learning.8

3. Next Level Learners recognize and attend to their learning as integrated emotional and cognitive beings.

Research in neuroscience underscores the role of emotion in effective thinking.9 Emotion helps to both fuel and guide our thinking processes. While people often talk about being coolly rational, research on people with severe brain damage that impairs the connection between emotion and cognition shows they are unable to make effective or efficient decisions.10 “Gut instincts”—also referred to as “bodily responses” or “somatic markers” in the literature—enable us to take informed shortcuts in decision-making11—whereas a purely logical or Bayesian approach to calculation would take extended time and bandwidth to arrive at a decision and requires more cognitive load or bandwidth than people have available. Even powerful computers exhaust time and resources performing a logical, Bayesian analysis on complex data.12 Thinkers who are encouraged to mine their gut instincts can be more effective13 and schools and workplaces can support people in making good use of emotion rather than ignoring it or banning it.

This integration of emotion and cognition is what makes us uniquely human and able to navigate complex problem spaces that require empathy, reflection, and the ability to move beyond pure logic in prioritizing options when engaged in decision-making. As argued by Dede, Etemadi, and Forshaw,14 it is what separates the possibilities for artificial intelligence in contrast to human potential when it comes to reckoning versus judgment in complex, uncertain times.

Next Level Learners embrace and become more attuned to the integrated role of emotion and cognition such that it allows them to bring their whole selves to learning and performance and enables them to manage and adjust for the many ways that the two interact. For example, one’s amygdala can set off emotional responses such that our body is flooded with adrenaline before our neocortex has been able to reflect upon a situation. Realizing this enables one to acknowledge what is happening and to respond in a way that mitigates or leverages the reaction depending upon the situation.

For a second example, emotion can motivate cognition; excitement about a set of ideas can help us to engage deeply with them and to get into a productive flow state that feeds into itself in a cyclic manner to propel further engagement. Knowing this can be especially helpful when one is avoiding a thinking or writing task. Dread can undermine engagement in a similarly cyclical pattern, so using strategies, such as getting started on a small part of a task that one feels confident about, can initiate a new dynamic.

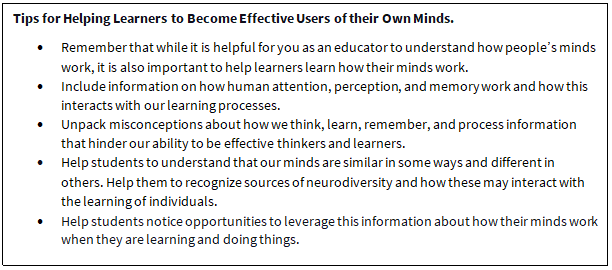

4. Next Level Learners are informed and effective users of their own minds.

In supporting agentive, self-regulating learning, it is not enough for educators to understand how people’s minds work; they need to help learners understand how their minds work. As we have written about elsewhere, we have user’s manuals to help us understand the working of all kinds of objects that we use every day.15 Our minds are central to who we are, how we think and learn, our every moment of existence, and yet many of us don’t know very much about how they work. Further, a lot of us have misconceptions about how we think, learn, and remember and process information that hinder our ability to be effective thinkers and learners.

Current research in neuroscience, cognitive science, and the learning sciences inform our knowledge of how our minds work, what supports effective learning, what type of strategies support different types of learning, and what difficulties we are likely to have. It helps us to know how human attention, perception, and memory work and how this interacts with our learning processes. It also helps us to understand how our minds are different—what sources of neurodiversity exist and how these interact with the learning of individuals.

In the vision of Next Level Learning set forth here, learners would have access to this information, regularly seek out additional information, and leverage this information forward in learning and performance. The research findings sometimes result in minor, but critical shifts in how we focus our learning efforts for more productive performance.

For example, when trying to remember information that has been read, instead of going back to look at it again and rereading it, a more powerful strategy is to try to call it forth in memory, consider what one does and does not recall, and then to go back and fill in the gaps.16 In other instances, the findings invite more substantive revisions, such as the realization that one needs to actually do something with the information in order to learn it deeply, and that doing something with it in more than one context will help to make it less wedded to the original context and more available to new contexts.

5. Next Level Learners are cultural beings who reflect upon their own cultural and contextual assumptions.

In our complex, interconnected world, we must be aware of the lenses through which we see and seek to understand the lenses of others. Just as we don’t notice the air around us that impacts us in so many ways, we are so embedded in our own cultures that we often cannot see our own cultural assumptions. And yet, as a basic part of our identity,17 these lenses color just about every aspect of our worlds—for instance, in schools, what it means to learn, whether to speak up or not, what constitutes a story, how we feel about the way science works, and so on. Beyond K-12, these cultural assumptions impact our work lives—in the structures that we expect, how we think about time, relate to others, engage with people in different roles and authority levels, and so forth.

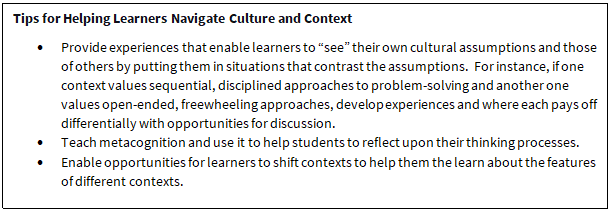

Often, we first begin to realize these assumptions when we find ourselves in a new context where our assumptions no longer hold or are considered outliers. Like a fish out of water or an astronaut in space, we then reflect upon the many aspects we took for granted. Metacognition, an ability to reflect upon one’s own thinking processes, is important for recognizing our embeddedness and for navigating between contexts and cultures.

In the vision of Next Level Learning set forth here, learners would have the opportunity to develop a reflective awareness of the assumptions embedded within cultures and contexts and to learn how to navigate other cultures while understanding and holding their own cultural identities. As lifelong learners, people will move between different contexts and cultures and must figure out how to learn the structures and assumptions within each.

How Do We Get to Next Level Learning?

The disruptions of the COVID-19 pandemic invited innovation in education that has the potential to support Next Level Learning. As discussed in the next piece in this series,18 the pandemic brought changes in how teachers talked about what characteristics their students need to be successful, self-directed learners. This came with increasing recognition that we need to help them to manage their own learning rather than managing learning for them, and that as they head out into the world, this is the learning that may serve them best. Of course, how we leverage the opportunity before us is up to us. We believe we owe our youth opportunities for Next Level Learning.

This introduction to Next Level Learning offers an overview of what it involves. It will be followed by a related series of documents and articles that explore the features and implications of Next Level Learner in greater depth. The research basis is further articulated and explored in these companion pieces. It also continues to evolve. Developing and studying pedagogies that support NLL will be an important next step in making this vision of the promise of human potential a reality.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge contributions from Robin Boggs, Chris Dede, Prince Ebo, Eileen McGivney, Mary Kate Morley Ryan, and Cameron Tribe.

About the Next Level Lab:

This work was developed through the Next Level Lab: Applying Cognitive Science for Access, Innovation, and Mastery (AIM) at the Harvard Graduate School of Education (HGSE) with funding from Accenture Corporate Giving (ACC). The Next Level Lab is pursuing this work as we articulate the findings from research in cognitive science, neuroscience, and learning sciences that inform approaches to education and workforce development. Our work sits at the intersection of mining extant research of promise; conducting research questions with the potential for high leverage impact; translating research on learning and the mind for public use; and innovating in the space of technology and learning to develop new visions for what is possible in developing human potential.

Tina Grotzer is a member of the faculty of education at the Harvard Graduate School of Education and a senior researcher at Project Zero. Tina directs the Causal Learning in a Complex World and Next Level Learning Research Labs where her research considers learning, performance, and expertise in a complex and uncertain world. She teaches courses in curriculum development and pedagogy.

Emily Gonzalez is an Educational Psychology PhD student in the Urban Education Policy program at USC’s Rossier School of Education and a former member of Harvard’s Next Level Lab. Emily’s research interests include investigating the impacts of pedagogy that offer youth agentive learning experiences and characterizing effective teaching for such, specifically to improve educational practice and systems.

Tessa Forshaw is an advanced PhD Student and Presidential Scholar at Harvard University where her work focuses on the intersection of design, learning science, and workforce development. She is on the Division of Continuing Education Teaching Faculty and is a researcher at Harvard’s Next Level Lab and a senior leader at the Silicon Valley design firm, People Rocket.

References and Further Sources

- Grotzer, T.A., Vaughn, D., Wilmot, W. (2019). The seven principles of “Living Curriculum.” Independent School Magazine on Reimagining Schools. Spring 2019, National Association of Independent Schools (NAIS).

- Often combined with some Backward Design towards societally valued understanding goals for other portions of their school program.

- Three forms of Learner-Centered Philosophy are common: progressivism, social reconstructionism, and existentialism (which is more closely aligned with Living Curriculum). https://www.theedadvocate.org/philosophies-education-3-types-student-centered-philosophies/

- Grotzer, T.A. & Perkins, D.N. (2000). Teaching intelligence: A performance conception. In R.A. Sternberg (Ed.), Handbook of intelligence, New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Fisher, F. T., & Peterson, P. L. (2001). A tool to measure adaptive expertise in biomedical engineering students. Paper presented at the Proceedings of the 2001 American Society for Engineering Education Annual Conference, Albuquerque, NM. Perkins, D.N. (2015). Flexpertise: A 10,000 Ft View, Accessible” https://www.learninginnovationslab.org/flexpertise-a-10000-foot-view-as-of-february-12-2015/

- Grotzer, T.A. (2012). Learning causality in a complex world: Understandings of consequence. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Engle, R.A., Lam, D.P. Meyer, X.S. & Nix, S.E. (2012). How does expansive framing promote transfer? Several proposed explanations and a research agenda for investigating them. Educational Psychologist 47(3), 215-231.

- Tishman, Perkins, & Jay, (1995). The thinking classroom: Learning and teaching in a culture of thinking. NY: Allyn & Bacon.

- e.g. Immordino-Yang, M.H., & Damasio, A. (2007). We feel, therefore we learn: The relevance of affective and social neuroscience to education, Mind, Brain, and Education 1(1), 3-10.

- LeDoux, J. (2003). The synaptic self: How our brains become who we are. NY: Penguin

- Damasio, A. (1999). The feeling of what happens: Body and emotion in the making of consciousness. NY: Mariner Books. LeDoux, J. (2015). The emotional brain: The mysterious underpinnings of emotional life. NY: Simon & Schuster. Gigerenzer, G. (2008). Gut feeling: The intelligence of the unconscious. NY: Penguin.

- Tutwiler, M.S., & Grotzer, T.A. (2014, November). Shortcuts and short-circuits: Heuristics and default assumptions in Bayesian causal learning models. International Mind, Brain, and Education Society (IMBES), Fort Worth, TX.

- Ledoux, J. 2015.

- Dede, C. Etemadi, A., & Forshaw, T. (2021). Intelligence augmentation: Upskilling humans to complement AI. The Next Level Lab at the Harvard Graduate School of Education. President and Fellows of Harvard College: Cambridge, MA.

- Grotzer, T.A. (2019). Becoming an Expert Learner. Cambridge, MA: President and Fellows of Harvard College.

- Brown, P.C., Roediger, H.L., & McDaniel, M.A., (2014). Make it stick: The science of successful learning. Cambridge, MA: Belnap Harvard.

- Nasir, N.S., Rosebery, A.S., Warren, B. & Lee, C.D. (2006). Learning as a cultural process: Achieving equity through diversity. In R.K. Sawyer (Ed.) The Cambridge Handbook of the Learning Sciences. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press pp. 489-504.

- Grotzer, T.A. (2021). From Engagement to Agentive: Why Is It Time to Raise Learning to the Next Level? Next Level Lab, at the Harvard Graduate School of Education, President and Fellows of Harvard College: Cambridge, MA.

Register for free

No Credit Card required

- Register for free

- Free TeachingTimes Report every month