24th August 2023, is GCSE results day

Chris hardly dares to look.

Geography, grade 6. That’s good!

Physics, grade 7. Wow! Fantastic!

But then English, grade 3. Oh no! I’ve failed! I’ll have to re-sit! Disaster!

How, though, does Chris know that the grade 3 is right? Might there be some mistake, an error?

Chris doesn’t know. Nor does Chris’s English teacher. Nor Chris’s parents. No one knows. How could they know? In the absence of a benchmark of ‘right’, how can anyone ever know? It’s all about trust. Trust in ‘the system’. After all, aren’t exams in England the “gold standard”? Of course they are!

And just in case there might – rarely – be a mistake, there’s the appeals process. Thank goodness! Yes, an appeal will correct any grading errors. That’s most reassuring…

The flaw in the appeals process

But that’s not the case. An appeal does not 'correct any grading errors'; some grade errors remain uncorrected even if appealed.

That’s because a ‘challenge’ (to use the correct term) allows a question to be re-marked only if a ‘review of marking’ identifies a ‘marking error’ – a failure of the examiner who originally marked that script to have complied with the mark scheme.

Which, at first sight, seems fine. But it isn’t.

Perhaps rather surprisingly, a grade can be wrong even if there are no ‘marking errors’.

This apparent paradox is readily explained, for we all know that different, fully qualified, examiners can give the same answer (slightly) different marks – as England’s exam regulator Ofqual themselves recognise (point 5 here). So a script might have every question marked in full compliance with the mark scheme yet receive different total marks of, say, 69 or 71 (out of 160) depending on who did the marking.

If grade 3 is defined as ‘all marks from 55 to 74 inclusive’, then the certificate will show grade 3 in both cases. But if the 3/4 grade boundary is set at 69/70, the certificate will show either grade 3 or grade 4.

That’s odd. It seems as if the candidate’s grade is the result of a lottery. As indeed it is.

This raises an important question: Which grade is right?

Ofqual resolve this dilemma by specifying the ‘definitive’ or ‘true’ grade as that resulting from the mark given by a subject senior examiner (page 20 here) – this being the benchmark of ‘right’. So let’s suppose, in this example, that the senior examiner’s mark is 71, corresponding to grade 4. Let’s further suppose that the mark actually given to the script was 69, so the candidate’s certificate shows grade 3. If this grade is challenged, no marking errors will be identified, for there are none. The ‘review of marking’ will therefore confirm the originally-awarded ‘non-definitive’ grade 3, ‘fail’, even though a senior examiner would have awarded the ‘definitive’ grade 4, ‘pass’.

How many undiscoverable exam grade errors are there?

That a ‘review of marking’ is not a re-mark, and that the appeals process might confirm rather than correct a ‘non-definitive’ – or, in simpler language, ‘wrong’ – grade, may not be news to you. But it might be to your students and their parents.

Nor do the exam boards make this clear. Reference to the websites of AQA, Pearson/Edexcel and OCR will verify that they each explain that a ‘review of marking’ checks for ‘marking errors’, but it is very easy for the ordinary person to assume this to be a fair re-mark by a senior examiner, for that is what they expect. For exams in England, only the website of the JCQ explicitly states that a ‘review of marking’ is not a re-mark (page 8 here) – as indeed does the SQA for those taking exams in Scotland. So perhaps the reality of the appeals process in England – and its limitations – should be more widely known.

That a ‘wrong’ grade might be awarded is worrying; even more worrying is the possibility that this grade error cannot be discovered and corrected. If this were rare, then the number of students damaged by this would be modest.

So how many ‘wrong’ grades are there? How many grades are awarded that correspond to legitimate marks, as given by a conscientious examiner, and with no marking errors, but grades that are different from the ‘definitive’ grade resulting from the mark given by a subject senior examiner?

To find out, during 2014 and 2015, Ofqual carried out an extensive research project in which entire cohorts of GCSE, AS and A-level scripts in each of 14 subjects were marked twice: once by an ‘ordinary’ examiner, and again by a senior examiner. Each script therefore had two marks, and two grades – one corresponding to the ordinary examiner’s mark, and the other the ‘definitive’ or ‘true’ grade resulting from the senior examiner’s mark. The two grades in each pair could then be compared, and the number of pairs for which the two grades were the same could be counted.

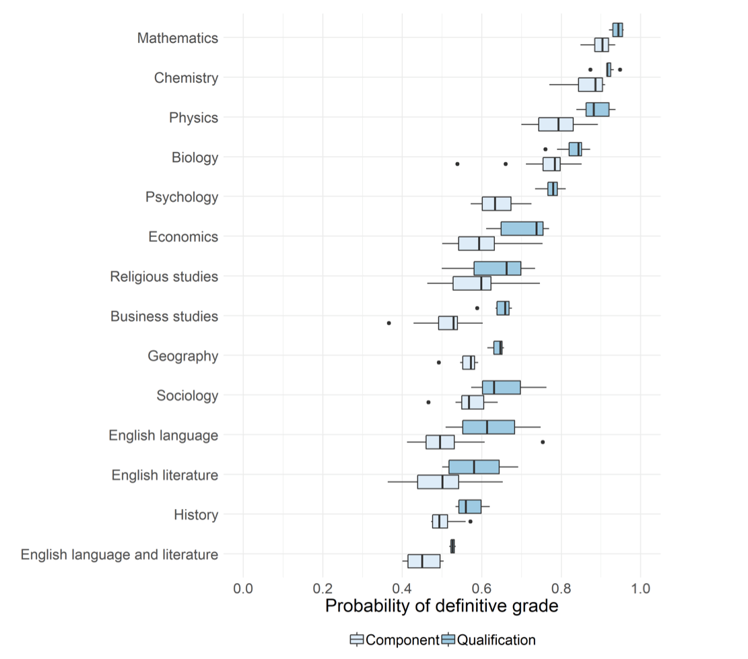

Some preliminary results were published in 2016, but it wasn’t until November 2018 that the most important results appeared as Figure 12 in Ofqual’s report Marking Consistency Metrics – An update, as reproduced here:

That chart is rather cluttered, so let me explain.

For each of the 14 subjects, the key feature is the heavy line within the darker box, for this answers the question: “For every 100 scripts in that subject, how many are awarded the same grade by both the ‘ordinary’ and the ‘senior’ examiners?”

Ofqual did not publish the numbers corresponding to this chart, but they can be estimated by reference to the horizontal axis. So, for example, for Economics, the heavy line is at about 0.74, or 74%, implying that the grades awarded to about 74 of every 100 Economics students are ‘definitive’ or ‘true’; for Maths (all types), about 96 in every 100; for History, about 56 in every 100.

Putting things the other way around… about 26 Economics students in every 100 are awarded a ‘non-definitive’ or (presumably) ‘untrue’ or ‘false’, grade – or, in my words, a ‘wrong’ grade. For Maths, about 4 grades in every 100 are ‘wrong’, and about 44 in every 100 – that’s nearly half – in History.

Those ‘wrong’ grades are ‘wrong’ both ways, so for Economics, out of every 100 students about 74 are awarded the ‘right’ grade, about 13 a ‘wrong’ grade too low, and about 13 a ‘wrong’ grade too high; for Maths, 96 in each 100 ‘right’, 2 too low, 2 too high; for History, 56 ‘right’, 22 too low, 22 too high.

Ofqual do not give an average figure across all subjects, but using the data they do provide (as in the chart shown), and weighting each subject by its cohort, the average comes out at about 75% ‘right’ and 25% ‘wrong’ (both ways). All those ‘wrong’ grades correspond to legitimate marks, and there are no ‘marking errors’. Accordingly, these wrong grades cannot be discovered, or corrected, by the appeals process.

That’s the answer to the question “How many undiscoverable exam grade errors are there?” It’s about one grade in every four. Or, in concrete terms, about 1.5 million of the 6 million grades awarded in England in August 2023.

To put that in context, for the summer 2023 exams, there were at most 1.2 million GCSE, AS and A-level candidates, to whom about 1.5 million wrong grades were awarded. On average, that’s about one wrong grade ‘awarded’ to every candidate in the land – including your students – and all with no prospect of correction by the appeals process.

Who knew what, when?

The research project I’ve referred to is mentioned in an Ofqual blog, authored by Ofqual’s then Chief Regulator, Glenys Stacey (later, Dame Glenys), on 29 September 2014. The project would have been initiated around that time. Here is an extract from a paper presented by Ofqual’s then Executive Director of Strategy, Risk and Research, Dr Michelle Meadows, at an Ofqual Board Meeting on 18 November 2015:

"28. The report on potential quality of marking metrics is complete and the findings will shortly be presented to SAG. This autumn we will be calculating a variety of metrics across GCSEs and A levels for all exam boards. Where there are differences in metrics within qualifications but across boards, we will analyse whether that is a feature of the assessment design, the data the metric is based on, or real differences in the quality of marking. We will consider whether these metrics could be aggregated to give meaningful and appropriate indicators of quality that could be published without having perverse consequences."

The ‘SAG’ referred to is Ofqual’s ‘Standards Advisory Group’. To me, the first sentence implies that not only has the research project on “the quality of marking metrics” been completed, but the corresponding report is finished too – a report that needs careful wording so that it can “be published without having perverse consequences”.

Ofqual’s report, Marking Consistency Metrics, was duly published one year later, in November 2016, but contained only limited findings. It was not until two years after that, in November 2018, that the results discussed here were published in Marking Consistency Metrics – An update.

On 10 December 2015, shortly after the Board Meeting of 18 November, Ofqual issued a consultation document proposing changes to the rules for appeals, including the introduction of the ‘marking error’ test – so blocking the discovery and correction of the grading errors resulting from the legitimate differences in academic opinion between an ‘ordinary’ examiner and a subject senior examiner. These were the same grading errors that Ofqual’s own research – as completed by November 2015 – quantified as affecting about one grade in every four. The ‘marking error’ test was adopted in May 2016 and first put into practice for that summer’s exams. It has remained in place ever since.

Ofqual have been somewhat reluctant to acknowledge the implications of their own research, but a ray of light was thrown into this murky corner at a hearing of the House of Commons Education Committee held on 2 September 2020. This was in the immediate aftermath of the ‘mutant algorithm’ fiasco, and most of the meeting was about that. But in September 2020, we all hoped that the virus had been conquered and that schools would soon be running normally once more, with ‘real’ exams being taken in summer 2021.

With that hope in mind, Ian Mearns, the MP for Gateshead, asked Ofqual’s then Chief Regulator, Dame Glenys Stacey (who had just been appointed on an interim basis to replace Sally Collier, who had stepped down) about the reliability of the grades likely to be awarded. Dame Glenys understood the question well, for it was Dame Glenys who commissioned the 2014-15 research project. This is the exchange:

Ian Mearns: "I am just wondering, therefore, whether one of the issues that you really should address, Dame Glenys, is that 25% of grades on an annual basis are regarded as being unreliable, either up or down."

Dame Glenys Stacey: "Thank you. I’ll certainly keep that in mind, and I look forward to speaking to you about it, Mr Mearns. It is interesting how much faith we put in examination and the grade that comes out of that. We know from research, as I think Michelle mentioned, that we have faith in them, but they are reliable to one grade either way. We have great expectations of assessment in this country."

Dame Glenys did not deny the question, nor did she push back. Rather, she replied: "We know from research that … grades are reliable to one grade either way."

That’s not quite the same as 'one grade in four is wrong' (or, as Ian Mearns put it, "25% of grades on an annual basis are regarded as being unreliable") – but it is very close, and the ‘research’ to which Dame Glenys refers is the research discussed here.

"Grades are reliable to one grade either way." Think about that. What does it mean?

It means that Chris, who was awarded grade 3 (‘fail’) for GCSE English, might have truly merited grade 3. Or grade 2. Or perhaps grade 4 (‘pass’). No one knows, nor can anyone ever find out… but Chris is consigned to the ‘Forgotten Third’ regardless.

Dame Glenys also said “I look forward to speaking to you about it”, but whether or not that actually happened, I don’t know. Dame Glenys was in post for only a few months, being succeeded in January 2021 by Simon Lebus, who in turn was succeeded by the current (but soon to step down) incumbent, Dr Jo Saxton, in September 2021.

Neither Simon Lebus nor Dr Saxton have acknowledged that grades are unreliable. Indeed, on the contrary, Dr Saxton has vigorously denied it – for example, on this Ofqual video (about 7:44) and also at a hearing of the House of Lords Education for 11-16 Year Olds Committee on 29 June 2023 (about 12:34:13 here).

Two weeks later, on 13 July 2023, at a further hearing of the Lords Committee, Lord Mike Watson of Invergowrie, referencing the conflicting statements made by Dame Glenys Stacey and Dr Jo Saxton, asked the then Schools Minister Nick Gibb: “Are grades reliable to one grade either way or not?” (I paraphrase – you can follow what actually happened by watching from about 12:23:23 here).

As you will see from the video recording, Nick Gibb was saved from answering by the Division Bell, but was asked by the Committee Chair, Lord Jo Johnson, to reply in writing. Nick Gibb did indeed send a letter to the Committee, dated 8 August 2023 – but with no reference to Lord Watson’s question, let alone providing an answer.

And on 14 August 2023, just before the 2023 A-level results were announced, Mary Curnock Cook, the former Chief Executive of UCAS, and Chair of Pearson (that’s Pearson as in Pearson/Edexcel) wrote a blistering blog with these opening words:

"In this blog, I want to provide some context and challenge to two erroneous statements that are made about exam grades:

* That 'one in four exam grades is wrong'

* That grades are only reliable to 'within one grade either way'"

The statement that “one in four exam grades is wrong” is mine, and I am fair game. But the statement that grades “are reliable to ‘within one grade either way’” are the words of Dame Glenys Stacey, given in evidence to the Commons Select Committee. Is that an “erroneous statement” too?

Over to you…

According to Dame Glenys Stacey, grades are “reliable to one grade either way”. So Chris’s grade 3 for GCSE English might be right. But it might not. The grade Chris truly merited might have been a 2. Or a 4.

But Chris can never find out, for there have been no ‘marking errors’, and, according to the appeals rules Ofqual introduced in 2016, Chris cannot have the script re-marked.

Dr Jo Saxton, however, takes a different view – to quote her evidence to the Lords Committee on 29 June 2023, “I can assure … young people who will receive their grades this summer that they can be relied on, that they will be fair, and that the quality assurance around them is as good as it is possible to be.” (Q135 here)

Which Chief Regulator is right?

Over to you.

What do you think – especially given the evidence of the chart from Ofqual’s own 2018 report? And if you might be leaning towards Dame Glenys…

* Do you think grades “reliable to one grade either way” are reliable enough?

* Do you think the current appeals process is fair?

And if not, what can you, your colleagues, your students, and your students’ parents and guardians do, collectively, to put pressure on Ofqual to deliver grades which are fully reliable and trustworthy? This, in fact, is very easy to do…

Dennis Sherwood is an independent consultant with particular expertise in creativity, innovation and systems thinking, and a campaigner for the delivery of reliable exam grades. Dennis is the author or co-author of many journal articles and blogs, and also 15 books, including Missing the Mark – Why so many school exam grades are wrong, and how to get results we can trust (Canbury Press, 2022).