The recruitment of Minority Ethnic (ME) educators in the UK has been a topic of discussion for some time, with reasons for such small numbers being somewhat vague. Anecdotally it has been suggested that recruitment is challenging because ME educators are entering teaching as mature candidates, or because they have taken an alternative route into teaching giving recruiters the perception that their qualifications are not as valuable.

Before we consider factors that impact on the recruitment and retention of ME teachers, consider the following:

- “46% of schools in England do not have BAME educators” (2020).

- “85.7% of all teachers in state-funded schools in England were White British” (2019)

- “…in 2015 only 8% of the trainee teacher cohort on the Schools Direct programme were from non-white backgrounds and only 14% of PGCE trainees were from BME backgrounds.” NEU

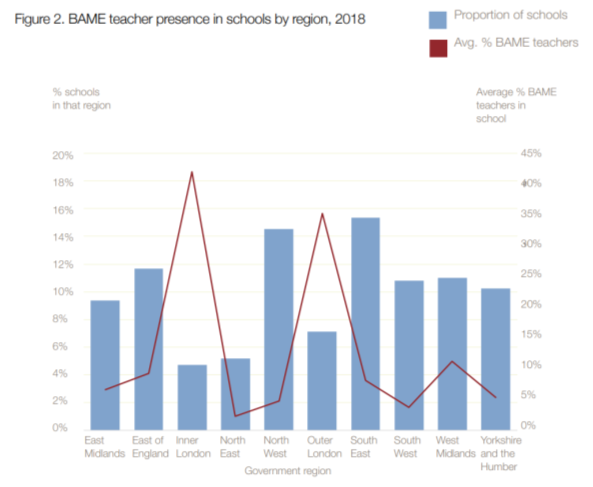

These statistics begin to tell a story, but figure 2 (below) is a clear visual representation of the problem.

It is apparent that London has a high percentage of ME teachers, but why? Is it because London has a higher proportion of people from ME backgrounds? Are ME educators relocating to work in ethnically diverse schools? Is it due to the high number of initiatives that have been piloted in the capital, such as ‘Lead First’ and ‘Lead London’? The geographical aspect of recruitment is not often discussed but it plays a crucial role and undoubtedly impacts networking opportunities.

Networks

In other industries, people use their networks to gain employment for peers, family, friends, and themselves. This approach to recruitment is visible in school leadership teams and extends to friends in these networks who know those in leadership positions.

Consider these examples. When recruiting for a role in a faith-based school, networking may comprise word of mouth in places of worship and the local community. Whereas a school focused on technology, or the arts, is likely to use an extended network of friends, peers in these respective industries who may have knowledge of or have considered a career in teaching.

In these instances, staff will adopt slightly different approaches to networking, which highlights the many variables that can affect recruitment – i.e., size and type of school, leadership team, geography, demography.

There is a perception that individuals from ME backgrounds do not know how to network, and this apparently is a reason for failing to progress in education establishments or gain places on governing boards. Although debated in education circles, there is no easily locatable source regarding this notion. However, when reviewing research relating to networking, there is an implication that ME educators are lacking an understanding of the importance of social capital in an education context, therefore being ‘blind’ to networking opportunities, and unaware of their position within informal groups.

“There is a need, however, to understand how social capital functions for job seekers and employers within different networks…especially because identity differences, and where one is positioned within a network, can impact access to job opportunities”.

(Jabbar et al. 2022) p. 2.

To support ME educators with recruitment and networking opportunities in the UK, various formal networks have been created: BAMEed Network, Black Men Teach, Black Teachers Connect, Young Black Teachers Network. Some are independent, registered charities, whilst others are a subset of teaching unions. Although these networks provide social support, pedagogical guidance, and offer networking opportunities, we must remain mindful that some networks will continue to maintain the status quo by virtue of the similarity of their members. These groups continue to “reproduce structural inequalities by gender and race” (Jabbar et. al. 2022). Membership to these networks is still by informal invitation (social groups, sports teams, dinner clubs), with membership extended to potential friends, those with whom we are comfortable, and those who are like us.

Smalls (2020) provides a good example of networking in the context of representation on boards. She talks about the importance of widening the net, being proactive and purposeful; you need to go where the applicants are. This should be the same in education. Do not always recruit in the same forums, you will get the same type of applicant – widen the net, look further afield.

Recruitment

Recruitment processes in education are broadly similar, with slight variations dependent on school type, location, and seniority of role. In the early 1960’s the Ministry of Labour Voucher Scheme became available to educators who trained outside of the UK, in a bid to get more teachers from ethnic minorities into our schools, but this was not altogether successful (Tomlinson 2008). Problems arose when Local Education Authorities did not want to employ educators from other countries. So, what is the government doing now? And what policies are being developed to increase the recruitment of ME educators?

Research and Government Policies

In answering the first question, you need only look at the most recent government policy paper “Diversity of the teaching workforce: statement of intent” (2018), and accompanying document outlining “information about the activity of the cosignatories”. The first page outlines exactly what the DfE plans to do:

“[The DfE will:] Consider equality and diversity as a priority through our recruitment and retention strategy to ensure people from all backgrounds are supported and that barriers to their progression are removed”

Gov.UK (2018)

However, upon further inspection, the latest policy on ‘Teacher Recruitment and Retention Strategies’ (2019), is vague in relation to the DfE statement of intent made in 2018. Generic barriers to teacher recruitment and retention are listed, but there is no indication of how the DfE intends to support applicants from ME backgrounds.

The situation is markedly different in Wales, with research conducted by Davies et al. (2022)Davies. et. al (2022) leading to meaningful change. Based on this research, the Welsh government announced a ‘New Plan’ (2021) which focuses on recruiting more ME teachers through ‘…targeting promotion of teaching as a career to more people from ethnic minority communities…[having] a requirement for Initial Teacher Education courses to work towards the recruitment of a percentage of students from ethnic minority backgrounds. [And introducing] additional financial incentives.’ This is an encouraging start.

Recent research published in England by Tereshchenko. A, et al. (2022) also provides several recommendations on how to improvement recruitment of ME educators, as well as suggestions on retaining this talent.

“A clear vision for school workforce diversity should be articulated in policy documents on teacher recruitment and retention in England…The commitment to diversity should be reflected in the policy initiatives such as the teacher retention and recruitment strategy and the early career framework reforms.”

“Initial teacher training (ITT) providers should consider placing BAME trainees in schools with diverse staff, especially amongst the senior leadership team.”

Like the research in Wales, this study was well received however, from its publication to the writing of this piece, the government does not appear to have actioned any recommendations.

Barriers to Entry

There are many barriers to entry for ME educators and these take several forms: actual and perceived. The following serves as an introduction to just a few of these obstacles.

Different Routes into Teaching

Barriers to recruitment may start early when making decisions on which route into teaching to take. The selected route will vary depending on personal circumstances, prior experience, age, geography, and so on, with educators from different routes having different experiences throughout the training process.

Barriers are not equal

The added barrier for some ME educators who are immigrants, is in a name. Some schools now adopt an approach to recruitment that encourages blind applications; a process whereby names, place of birth, and education, are not visible to those making the initial selection. The application is based on skill.

The advantage of a skills-based approach is that you gain a pool of candidates with the key skills you require for the position (teaching qualification, classroom experience, report writing, communicating…). You will not be biased by unfamiliar, hard to pronounce names, or prestigious universities. The disadvantage however is that you may eliminate candidates who have entered teaching via alternative routes in the initial stages of your process. Consider the following questions:

- What if those educators who have taught successfully in schools in their home nations for more than five years but have a different teaching qualification? How is their application viewed ‘fairly’?

- How can an educator like this be employed when their skills are proven but there is no paperwork to support them?

The government has developed a solution: International Qualified Teacher Status (iQTS). This a new route into teaching and currently on trial in England (six schools). Although it aims to broaden the pool of teacher talent, it may continue to promote division, effectively setting immigrant educators aside from those born in the UK.

“[The] DfE will recognise iQTS as equivalent to QTS, subject to the will of Parliament, via an amendment to regulations early in 2023. This means those who have successfully completed the iQTS qualification with an approved provider will be automatically awarded QTS.”

Gov.uk (2021)

As with the aforementioned voucher scheme of the 1960’s, will there be hesitancy from school leaders, recruiters, local authorities? They may shy away from employing educators who have iQTS as opposed to QTS. These remain open questions.

A final point to raise is the financial barrier for schools when recruiting from abroad. Schools must also take into account visas and immigration charges (which range from £536-£1476 depending on school size). There are many steps involved in these applications and schools may be reluctant to employ educators via this route (see section 2 of government guidance).

The Distribution and Roles of ME Educators

Though barriers to recruitment have been discussed, it is worth briefly highlighting stereotypes which may hinder recruitment. Although there are ME educators in our schools, the perceived and actual distribution of ME educators can sometimes be a hindrance in terms of recruitment.

How could this distribution be a hindrance? If the perception is that ME educators only take on roles with Pastoral responsibilities or roles related to Mathematics, Science, or Physical Education, if this is not your passion, it is unlikely you would train or encourage anyone you know to consider this career path.

“…assumptions that Black teachers are well-suited to teach dance or physical education, or that teachers from the Indian sub-continent are ideal math teachers… [M]inority ethnic teachers are conceived to fill certain vacancies and not others thus limiting the chances of recruitment to certain subjects, such as English language, or positions, such as headteacher” p.32

Lander and Zaheerali (2016)

Retention of Minority Educators

The retention of ME educators is challenging with many staff leaving due to the pressures of the environment. Although workload is an issue for all educators (particularly during/after COVID19 lockdowns), research has found that the ‘hidden workload’ is a contributing factor for educators from ME backgrounds. Interviews with teachers have found this includes items that “would take up considerable time, but were not rewarded financially or in terms of career progression included ‘Black History Month’ and ‘anything’ related to BME students – ‘You become the spokesperson for everything BME.” Haque & Elliot (2017)

The ‘Making Progress’ report is a fascinating and informative read which explores in detail other reasons for ME educators leaving the profession: these extend to racism, colourism, a lack of ethnic diversity amongst leadership teams, associated pressures of being a role model, mental health issues, and the glass ceiling, to name a few.

Next Steps

As discussed, research has been conducted into how to recruit ME educators in Wales, with the Welsh government already taking steps to make a change. In England research has been conducted but no action appears to have been taken.

At a local level, ‘BAMEed Bristol & SW’ is collaborating with the ‘Regional Delivery Directorate for the South-West’ to change recruitment practices at a strategic level. This project is in its initial stages with members meeting monthly to share best practice and refine current processes.

I am hopeful that similar initiatives are happening nationally. If you are involved in a government initiative or piece of research related to the recruitment and retention of ME educators (particularly in England), do share details of what you are working on, or post a link in the comments. We need to work together to make a change.

Sharon Porter appeared at Bett earlier this year alongside the Chair of BAMEed Bristol & SW (Domini Leong), to present a speaker session on ‘Developing racial literacy among staff and students in educational settings’: https://www.bettshow.com/

Register for free

No Credit Card required

- Register for free

- Free TeachingTimes Report every month