A strategy for the continued improvement of great schools: Growing the Top

It is an adage that outstanding schools don’t remain outstanding by standing still. ‘The key question for school improvement is what are outstanding schools doing that sets them apart, and how can we bottle it?’ asked Dr Josephine Valentine, who conceived this programme aimed at finding out...

The OECD states that ‘one of the marks of any professional is the ability to reflect critically on both one’s profession and one’s daily work, to be continuously engaged in self-improvement that will lead to improvement in students’ learning’. But self-improvement needs to be fuelled by knowledge of best practice elsewhere, informed by research and mobilised through effective innovation. Berwick has argued that integrating these three bodies of knowledge in a structured way creates a virtuous learning community with the power to improve student outcomes.

On this principle, Challenge Partners developed and orchestrated the Growing the Top (GtT) programme, which aimed to support the ongoing improvement of highly effective (or ‘stand-out’) partner schools by pooling their expertise to acquire new knowledge, access research and find innovative solutions to knotty challenges. Challenge Partners is a learning community and registered education charity of about 500 schools, grouped around 44 hub schools, which collaborate to improve each other and the wider education system so that all children benefit.

How the programme was designed and implemented

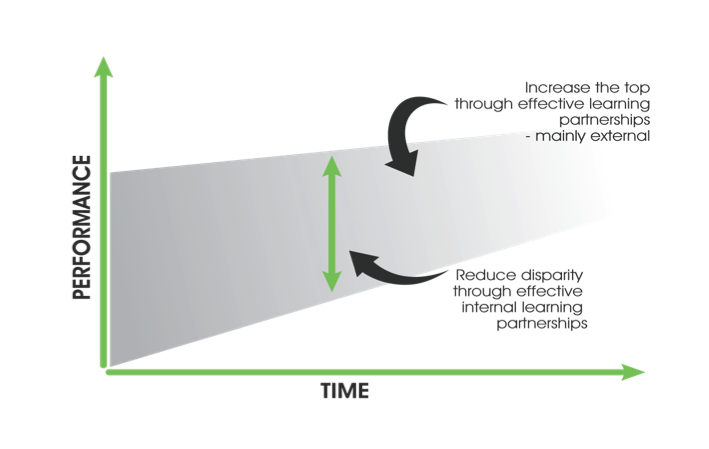

The GtT programme design was based on two core principles: upwards convergence and knowledge sharing (figure 1). Upwards convergence is the idea that the system will keep improving not only by improving the lowest performing schools and groups within schools but also through stimulating those at the top to get better.

Knowledge-sharing is based on what is valued from research as well as the ‘assumption that knowledge already resides in the lived daily experience of teachers’. Great practice and expertise exist within our schools, but the system struggles to move this knowledge around. The idea was to create a mechanism by which stand-out schools could both share aspects of the practice that contributed to their effectiveness and work together to find solutions to an ongoing challenge in each of the schools.

The GtT programme works by grouping the cohort of participating outstanding schools in trios, engineered so that there is a spread of geographical areas and school types (selective, single-sex, faith etc) in each trio. Each school in turn hosts a visit by the headteacher and a senior leader from the other two schools in the trio, aiming to:

- showcase one or two aspects of systemic excellence in the school, and

- present a systemic challenge, which the visiting leaders are invited to consider and help solve.

The agenda for each school visit day ensures that both the visitors and the host can leave with tangible school improvement ideas or ‘take-aways’ both by gleaning great practice and by participating in high level clinical dialogue around the area of challenge, which is often common to the visiting schools. Half the day is used to focus on one or two hallmarks of excellence, half on the area of challenge identified by the host school (figure 2).

Figure 2. Outline structure of trio visit days

| Morning elements | |

| Facilitated contracting, then scene-setting by the school | In which protocols are agreed and the headteacher presents the school and its strengths and challenges |

| Consideration and discussion of two aspects that contribute to sustaining excellence | In which visitors examine the areas of excellence through observation, presentations and discussions with key players |

| Afternoon elements | |

| Exploration and discussion of a systemic challenge | In which the challenge is described, and visitors given opportunities to explore the challenge, establish facts and suggest evidence-informed approaches |

| Round-up | In which host and visitors reflect on knowledge and understanding gained and state what they will take away from the experience |

Each trio visit is led by a trained facilitator, who is also an experienced and successful school leader. The facilitator is responsible for moving the day forward and keeping participants to task while enabling the host to participate fully in the day. The facilitator uses their expertise judiciously to lubricate and raise the level of professional dialogue, maintain focus and promote a climate of openness and collaboration throughout the day.

In addition to the school visit days, the whole cohort of participating schools comes together three times during the year for centrally organised day-conferences. These events are designed to facilitate knowledge sharing between trios and provide presentation inputs from research, the corporate world and the private education sector, designed to inform and challenge thinking and stimulate conversations and discussions around approaches to the continuous improvement of participants’ schools.

How effective was the programme?

The programme was evaluated in its pilot year (2018-2019) using a mixed methodology that combined pre- and post-programme surveys of participants with case studies and testimonies from participating head teachers and senior leaders. The evaluation focused on the design and implementation of the programme and its processes, as well as the initial impact on participating schools. Overall the evaluation was designed to test the efficacy of the GtT programme, particularly the facilitated learning trios, in terms of how well knowledge would be shared and implemented to produce positive change and improvement, reflecting the principle of upwards convergence.

The evaluation demonstrated that the Growing the Top programme is an effective vehicle for developing professional relationships, moving knowledge around and sharing expertise which all supported schools to leave the programme with tangible ideas on improving on their previous best (see figure 3.)

Figure 3. End of visit responses

| End of visit responses (n=97): response scale 1 (strongly disagree) to 10 (strongly agree): rank order | Mean | Mode | Median | SD |

| I am leaving today with some tangible ideas of how my school could improve on its previous best. |

9.4

| 10 | 10 | 0.95 |

| I had sufficient opportunity to deepen professional relationships with colleagues in my trio. | 9.0 | 10 | 9 | 1.1 |

| Existing knowledge on school improvement has been shared today. | 9.0 | 10 | 9 | 0.99 |

| New knowledge on school improvement has been developed today. | 8.8 | 9 | 9 | 0.97 |

| I have increased my ability to share knowledge effectively with others. | 8.3 | 8 | 8 | 1.3 |

| I had sufficient time to reflect on learnings. | 8.2 | 10 | 8 | 1.5 |

(Matthews and Killick, 2019: 22)

A community for continuous improvement

In achieving the programme principles, the cohort of schools taking part in the GtT programme was a subset of the Challenge Partners community of schools. School trios drawn from this cohort formed time-limited and mission-focused professional learning communities (PLCs). The trios can be conceived of as pop-up think tanks that enable senior leaders to explore key issues together, following the principle of upwards convergence. These inter-school think tanks serendipitously reflected the five attributes that Vescio, Ross and Adams’ in 2008, after Newmann et al. in 1996 used to define an effective professional learning community:

- shared norms and values

- ‘deprivatised’ practice

- reflective dialogue

- collaboration

- collective focus on student learning

i. Shared norms and values

Louis et al argued that “fundamental to any community is a sense of common values and expectations of and for each other” The Growing the Top programme used specifically trained facilitators who at the beginning of the standardised agenda for each visit day conducted a contracting session between participants. The evaluation of the programme affirmed that these sessions reinforced a set of shared set of norms and values. Participants commented that facilitation was “well balanced and non-judgemental” and “ensured that all individuals had an adequate amount of time to share ideas”. Furthermore, almost all schools strongly agreed that: “The facilitator was trusted and effective in creating an open and honest environment” and that “The facilitator set clear and agreed boundaries and ethics in ‘contracting”

The norms and values shared across the three schools in each of the trios were fundamental to group interaction and learning. The trios voiced joint reflections, as follows, at the end of the programme.

“Although geographically dispersed, our schools turned out to have many principles, values, approaches and policies in common, despite very different contexts. Each school has its own individual language and approaches, but when you dig down, you find we have common fundamentals. These were reflected throughout the organisations, right down to what students and staff said and did. Very heartening. Perhaps this shows you have to have universally strong values to succeed and remain successful over time.” (Trio 3 reflection)

The facilitation of this open environment with a common understanding of expectations of challenge also supported the participants to ensure the success of attribute number two: deprivatised practice.

ii. De-privatised (i.e. openly displayed) practice

Schools in the Challenge Partners’ Network of Excellence are schools who by the very nature of them choosing to join a national network of schools are outward looking and open to challenge. By joining the network, they are buying into an annual peer review and inviting scrutiny of their practice. The GtT programme took this notion of opening up one’s school’s practice to examination and peer consultancy one step further than peer review. The programme provided a platform and a safe environment, importantly free of judgement, in which schools could be open about their challenges as well as their successes without feeling vulnerable. One trio expressed the virtuous learning relationship as follows: -

“All three schools had bought into the philosophy, openness and transparency that was needed for this programme. All said how great it was when we were in the other schools. The visits were so important in terms of our journeys. They gave us so many insights and ideas to go away and try.” (Trio 1)

The GtT programme exposes leadership practice across participating schools. By opening their schools to critical friends and fellow experienced professionals, participants “come to know each other’s strengths and can therefore more easily obtain “expert advice” from colleagues.”

From the pilot evaluation of the programme, all respondents either agreed or strongly agreed to the propositions that: “arrangements for our focus on systemic excellence within the school provided informative evidence and insights” and “arrangements for our focus on systemic challenge, allowed us to understand, investigate and offer advice on the issue(s)”. This indicates that host schools opened themselves up to their visitors and allowed themselves to be exposed and vulnerable not only in order to share great practice, but also to enable open discussions about areas in which they were struggling. This allowed honest and effective conversations about the issues with professional colleagues, with one school explicitly commenting on noting “the importance of trust and openness, being confident to expose and explore challenges”

iii. Reflective Dialogue

Establishing both deprivatised practice and shared norms and values enables reflective dialogue to take place which “leads to deepened understandings of the process of instruction and of the products created within the teaching and learning process.” (Louis, Marks and Kruse, 1996: 761).

Schools participating in Growing the Top proceed through two layers of reflective dialogue, firstly internally with schools’ staff and leadership teams to decide upon what areas of systemic excellence and challenge they wish to focus on during their visit day. Subsequently they engaged in open and professional dialogue with their trio and facilitator. The impact of these discussions led one participant to comment; “we have achieved a fresh perspective as well as ‘challenged our own thinking’ on current procedures and best practice moving forwards.”.

“We left each school buzzing with ideas. The visits had an immediate impact on us all. We felt galvanised, laying ourselves bare, having the opportunity to ask questions but also to listen. This has left us wondering how to instil the same belief in the people who are going to be driving some of the ideas going forward.” (Trio 2)

iv. Collaboration

The concept of collaboration is a central feature of professional learning communities. A collaborative community working together enables “members [to] call on each other to discuss the development of skills related to the implementation of practice

“We liked living and breathing the ethos of other schools in different locations. We are surprised at how much we have learned from each other in such a short time. Schools very local not always so keen to share. This low-cost approach is a great way to drive school improvement.” (Trio 1.)

Demonstrating that collaboration is really at the heart of the Growing the Top programme,, one participant noted that “it was very valuable to have the perspective of other professionals on areas of systemic challenge, bringing their experience and ideas to bear on issues similar to our own or sometimes very different”, (). Whilst others stated that as a result of effective collaboration, they received “‘great ideas’ for tackling their own systemic challenge and finding that their issues were not unique

v. Collective focus on student learning

The final qualifier, and arguably the purpose of any school-based professional learning community, is that the group must have a collective focus on student learning. Schools were not required or asked to choose areas of systemic excellence and challenge that were directly linked to student learning. However it is noteworthy that, of the 21 participating schools 15 of them chose areas of systemic challenge were directly focused on outcomes and progress for particular groups of pupils and/or subject areas rather than indirectly on outcomes via teacher CPD or wider school development Some examples of the areas of systemic challenge were:

- progress of boys (KS3 and KS4)

- variability in post-16 outcomes

- quality first teaching in KS3 for pupils with SEND

- improving performance in subjects needing fluent academic reading and writing

- closing the gap for disadvantaged students

- demographic gaps (Black Caribbean boys and disadvantaged students).

Bearing in mind that these schools were selected to participate in the programme due to the excellent progress and outcomes for their students, it is interesting that the chosen focus often related to making further marginal gains in the learning outcomes of specific groups of students.

External Facilitation

A distinguishing feature of the Growing the Top programme, and what enabled the time limited “pop -up” nature of the learning groups to still be effective, was the use of current educational practitioners trained as facilitators. Schools readily adhered to the structure of the day designed by Challenge Partners and welcomed facilitation, which they described as “well balanced and non-judgemental”, and fundamental in “helping the host school manage the day and achieve outcomes” and noted that the facilitators themselves brought “their own ideas and experience to the table when appropriate or needed”. The impact of this can be seen in figure 4 which clearly demonstrates the positive impact of the facilitator.

Figure 4. Participating schools’ perceptions of facilitation (n=14)

|

| Agreement with proposition |

| |||||

| The facilitator | SD 1 | D 2 | TD 3 | TA 4 | A 5 | SA 6 |

x̅ |

| Set clear and agreed boundaries and ethics in ‘contracting’ | - | - | - | - | 1 | 13 | 5.9 |

| Understood the group dynamics, involving members and making them feel good about being involved | - | - | - | - | 4 | 10 | 5.7 |

| Was trusted and effective in creating an open and honest environment | - | - | - | - | 2 | 12 | 5.9 |

| Was attuned to what was going on and intervened when appropriate | - | - | - | 1 | 2 | 11 | 5.7 |

| Was skilled in observing, listening, reading body language, understanding human behaviour and intervening sensitively | - | - | - | 1 | 3 | 10 | 5.6 |

| Was successful in maintaining the focus and momentum of discussions | - | - | - | 1 | 2 | 11 | 5.7 |

| Ensured that both the school and visitors could express what they had gained and would take away from the visit | - | - | - | - | 3 | 11 | 5.8 |

| Added value to your experience of the day | - | - | - | 1 | 4 | 9 | 5.6 |

(Matthews and Killick, 2019: 20)

Outcomes

The GtT programme demonstrably reinforced the group of 21 schools as a virtuous learning community in terms of Berwick’s three characteristics: research, best practice and effective innovation. The research dimension was promoted through the inputs to cohort events and by the majority of participant schools,that demonstrated how research had contributed to their strategies and practice. Research informed examples included: approaches to change management, school improvement strategies, subjects such as mathematics, middle leader development and mental health and wellbeing. Shared best practice included curriculum planning, driving up standards, intervention strategies and student and staff coaching. The schools showcased many innovative approaches including, for example: year 8 baccalaureate, personal development and ilearn, staff personal improvement plans, and maximising boys’ progress.

The schools cited many ways in which they learnt from each other by discovering what worked best in other places and pooling knowledge about systemic challenges. The latter included brainstorming solutions as well as sharing knowledge and research about effective practice. Schools were predisposed to following up the most fruitful themes by creating links between other senior and middle leaders in the school trios.

The third and final cohort meeting included trio witness statements of what they had taken away for the programme and – in many cases – already begun to implement. The greatest potential of the programme lay in systemic challenges that centre on raising the relative achievement of specific groups, including boys, disadvantaged children and under-performing sixth formers. The findings showed that sharing what works through Growing the Top undoubtedly helped schools to tackle these issues.

Conclusion

The Challenge Partners’ Growing the Top programme provides an effective and efficient platform for excellent schools to share existing knowledge of great practice, co-create solutions to challenges that they share and explore their journeys to tackling issues that other schools may just be starting out on dealing with.

Although the success factors of the GtT programme align with the attributes of effective PLCs, the GtT programme’s evaluation expands Stoll et al.’s concept of PLCs, limited to the school as a community with PLCs only developing and succeeding with “the active support of leadership at all levels”. The impact of learning cascades beyond the participating school leaders since the GtT model provides space and opportunities for the ongoing collaboration for various inter-school groups during and after completion of the initial programme. Essentially, the development of an effective and inter-school PLC at senior leader level also resulted in a “trickle-down effect” with inter-school pop-up learning groups forming between middle leaders, encouraged and facilitated by school leadership designed to explore issues in greater depth. In trio 6, for example,

“The contacts we have made and ideas and policies we have shared are providing the basis for linking people at different levels across the schools. This has started with work on English. We plan to meet again next year to review progress stemming from the programme.”

These outward looking “pop-up”, inter-school learning groups were catalysed through the GtT programme and then emulated the processes which encompassed three very important conditions for success.

Enhancing the well-established social capital within Challenge Partner schools

The development of the Growing the Top programme within the existing Challenge Partners Network of Excellence means that the programme can take advantage of established social and moral capital and outward looking perspectives that are part of the makeup of the partnership. Schools who participate in the GtT programme are already used to opening their doors to visitors and welcoming external challenge through peer reviews.

External facilitation

By absolving principals of host schools from facilitation responsibilities, their focus can really be on effectively presenting aspects of the school and contributing to open dialogue and collaboration. The facilitator shoulders the practical responsibility for creating an effective and open learning environment and ensuring that the day runs smoothly and effectively

Challenge Partners as a broker

Centralised project management ensures that the logistics of visits, identification of topics and quality of agendas were secured before visits took place and that cohort meetings added value to the programme. Additional quality assurance oversight for the programme and training of facilitators ensure that the learning experiences are effective and high quality for all participants.

This format of facilitated PLC offers a powerful option for effective and efficient inter-school development at a time when schools are feeling increasingly squeezed. With the success of the pilot year of the Growing the Top programme, Challenge Partners has been able to offer the programme more widely in academic year 2019-2020. The programme has been expanded to include primary and special schools to see whether if the impact can be replicated with different phases.

Roisin Killick is the Challenge Partners internal evaluator for GtT.

Peter Matthews is visiting professor at the UCL Institute of Education, London. Correspondence: petermatthewsasociates@gmail.com

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the 21 participating schools who allowed recordings of conversations around their areas of systemic excellence and systemic challenge to be taken, and who provided information and feedback for the evaluation.

They also wish to thank Liz Smissen who co-delivered the programme, Dame Sue John, programme Executive Sponsor and Dr Josie Valentine OBE, CEO at the Danes Educational Trust and programme Lead Practitioner who developed the Growing the Top programme and provided invaluable feedback on the evaluation. This article draws from research commissioned by Challenge Partners and described in Matthews and Killick (reference below).

References:

- Valentine, J. (2019) What makes some schools stand out? Schools Week. https://schoolsweek.co.uk/what-makes-some-schools-stand-out/

- OECD. (2016a) “What makes a school a learning organisation? A guide for policy makers, school leaders and teachers.” Accessed October 25. https://www.oecd.org/education/school/school-learning-organisation.pdf

- Berwick, G. (2018) Why we are focusing on hub effectiveness? Characteristics of developing and sustaining an effective hub, London, Challenge Partners Accessed 15 November 2019 http://www.georgeberwick.com/publications/papers/

- Berwick, G (2017) “Upwards Convergence.” Accessed 30 October 2019. http://www.challengepartners.org/sites/default/files/files/CP-Upwards-convergence-brochure.pdf

- Buysse, V. Sparkman, K. & Wesley, P. (2003). Communities of practice: Connecting what we know with what we do. Exceptional Children, 69 (3): 263–277.

- For a similar approach see Handscomb, G. and Snelling, R. (2003) School Improvement and Peer Evaluation. Forum for Learning and Research Enquiry (FLARE). Essex County Council.

- Vescio, V., Ross, D., and Adams, A. (2008) “ A review of research on the impact of professional learning communities on teaching practice and student learning.” Teaching and Teacher Education, 24(1):80-91

- Newmann, F. M. and Associates (1996) Authentic Achievement: Restructuring Schools for Intellectual Quality. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Defined as “frequent examining of teachers’ practice, through mutual observation and case analysis, joint planning and curriculum development” (Newmann & Wehlage, 1995 in Stoll, L. Bolam, R. McMahon, A, Wallace, M. and Thomas, S. (2006) “Professional Learning Communities: A Review of the Literature.” Journal of Educational Change (7): 221-258. doi: 10.1007/s10833-006-0001-8.

- Louis, K. Marks, H. and Kruse, S. (1996) “Teachers’ professional community in restructuring schools.” American Educational Research Journal, 33 (4): 757-798.

- Matthews, P. and Killick, R. (2019) “Growing the Top’ - Extending excellence in a learning community of stand-out schools”, Challenge Partners, London.

- See: Stoll, L. Bollam, R. McMahon, A, Wallace, M. and Thomas, S. (2006) “Professional Learning Communities: A Review of the Literature.” Journal of Educational Change (7): 221-258. doi: 10.1007/s10833-006-0001-8. and Vescio, V. Ross, D, and Adams, A. (2008) “A review of research on the impact of professional learning communities on teaching practice and student learning.” Teaching and Teacher Education, 24 (1): 80-91.

- Louis, K. Marks, H. and Kruse, S. (1996) “Teachers’ professional community in restructuring schools.” American Educational Research Journal, 33 (4): 757-798.

- Participant quote in Matthews, P. and Killick, R. (2019) “Growing the Top’ - Extending excellence in a learning community of stand-out schools”, Challenge Partners, London.