Innovation – it’s a word we see everywhere. Magazine’s, government reports, school mission statements are all using it and have been for some time, but why does it continue to grab our attention and is it all a bit of a myth or is it something we should be investing more time in? We would argue the latter, but you can’t just decide to be innovative, that would be too easy. The rewards on offer are plentiful, but like anything you achieve well in your school, successful innovation will require structure, leadership and resources.

Let’s return to basics and ask ourselves ‘what do we mean by innovation?’ If you are a school that embraces innovation you should be able to define what that is. For many leadership teams there is confusion here with creativity, but creativity is just the first step of effective innovation. Innovation explores new ideas to add value – keep it simple. Being creative is great, it’s a first step in innovation, but does your creative idea add value to your school? Would putting some more resources into it create more value or could you get more return on your efforts elsewhere? Organisations that are skilled in innovation can answer these questions because they actively manage the innovation process. Don’t misunderstand this, value doesn’t have to be about pounds. It could be value around motivating staff and pupils, attainments levels, health, it could be societal value and, yes, it could save you money. The point is you have to know what you are trying to achieve to know whether you are being successful in getting there.

Next up is the question ‘who’? Professor John Bessant is one of a number of people who has studied successful innovation in great depths. His numerous books are well worth a read for those wanting more detail, but in essence he broke down organizational innovation into a number of areas. Some organisations had specialist teams dedicated to the process, in others people had specific time to innovate (you may recall Google hitting headlines for allowing staff 20% of their time to explore new ideas). The model schools need is often referred to as ‘High Involved Innovation’ (HII). This means getting as many people as possible involved in developing and implementing ideas, all of whom may add a little be more value due to the different skills, experiences and resources we have to hand. Think about the amount of people who want your school to be successful; you, students, carers, families, governors, local communities, suppliers. The list is huge and with every pair of hands that comes through your doors comes a free brain! Just imagine if you could list all the things they could offer you, how big would that list be? Every skill they had, every bit of waste material they throw out at work, every piece of experience that might help you. I’ve actually seen some schools try to catalogue this, but it can’t be done because it never stops changing. So rather like taking a pushchair across a beach, don’t push, pull. Don’t waste time discovering skills and then ‘push’ them into areas, instead create a ‘pull’ of a new idea (from your creative ideas), but become more skilled at managing and publicising that idea so that people get drawn into and make their own pledges about helping. Volunteers are much more likely to stick with a project in this way, they feel like they own it, can steer it and will want to see it finished.

A great example of this comes from David MacLeod in his book ‘The Extra Mile’ where he explores innovation within the context of workforce engagement. He was the marketing director for a large paint company that was facing some serious challenges due to falling sales. David could have brought in all the usual roles to come up with a plan but, being the kind of guy he is, took a different route. He looked for ideas anywhere he could whether they were friends, colleagues or customers. He looked for any ideas that were worth exploring and then supporting people in exploring them further. People really trusted that he was genuine when he wanted them to innovate, and so threw everything they had at the challenge. There were of course false starts, decisions to be made and resources to be managed, but the motivation was high. In the end, somebody stumbled across a single snippet of information about a company in America that was trying to make a range of ‘off-white’ colours. It may sound obvious now, but in the mid-eighties this was something new. A carefully managed risk was taken and the results were staggering. The plant went from working 5 normal days a week to working 24/7 and the business was completely turned around.

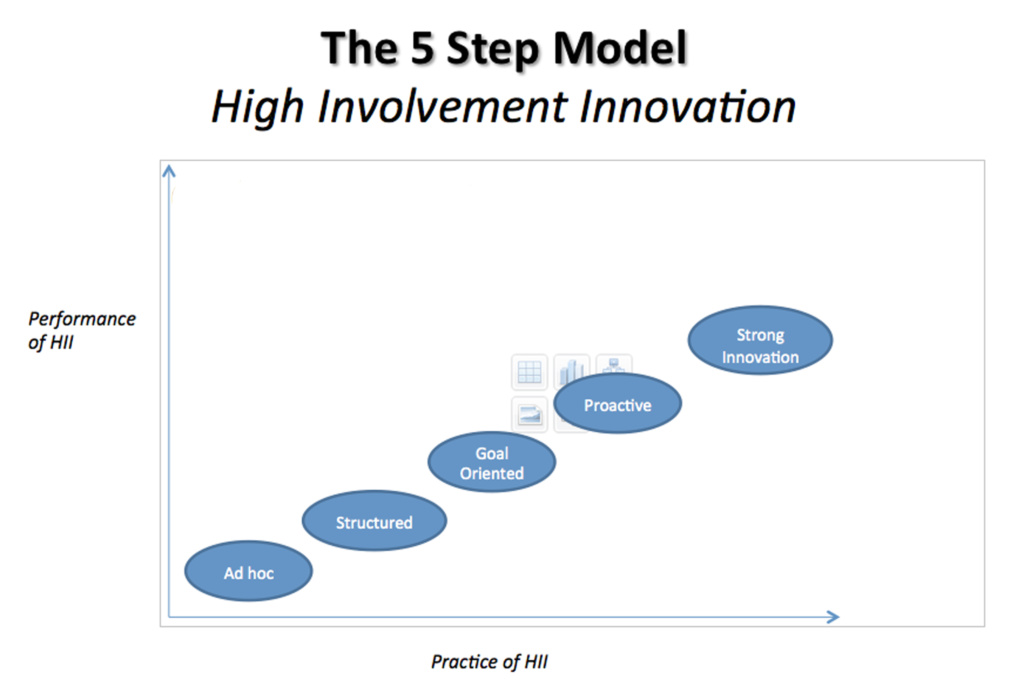

Is there any link between a paint plant and teaching? Absolutely. Teaching leaders don’t need to come up with ideas, but they need to become more effective at planting the seed of what is required, harvesting the response and then managing development and implementation. In Professor Bessant’s research he examined hundreds or organisations and summarised this idea as plotting the practice of innovation against the effectiveness of innovation. What he found was that there is nearly always a direct correlation between the two giving a stepped process in which oraganisations seeking to improve the value they receive from overall innovation could aspire to the next ‘step’. At Innovation 4 Education we work with a simple diagnostic for teams of any size to understand where they are now, and what their next steps should be to progress.

Beyond the light bulb moment

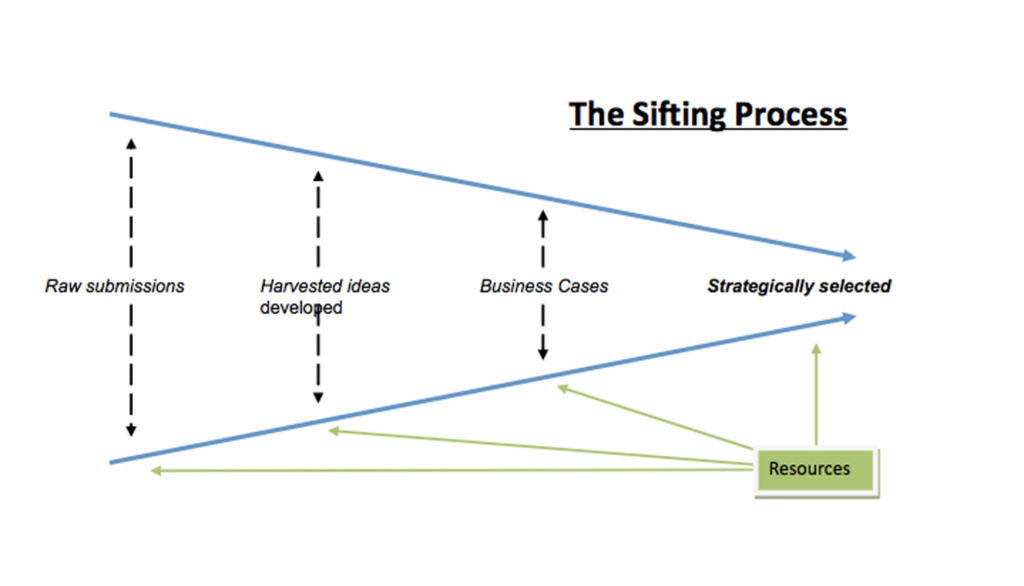

Believe it or not, getting ideas is not the hard part. Once you send out a few areas that you would like help on, ideas come. Most people want one of two things when they offer their input. They either want to stay involved to see it through to an outcome, or simply to see some progress. When there is a simple process in place for these two things to happen, the appetite for getting involved is quite amazing. All of these principles apply whether you are a school 50 pupils or a school of 1500, processes can be simple and scalable, but your challenge will be too manage the ideas rather than just try your best with finite resources. For this we use a simple model.