Learning habits are so important to success in life, yet time is so rarely dedicated to developing them in school. We take for granted skills like being able to communicate effectively with people in a range of contexts, knowing how to create a plan of action to achieve a long-term goal and staying resilient in the face of challenges. It is these competencies which employers are saying young people entering the workforce are lacking, so we cannot assume that all learners will simply pick them up as a matter of course.

Project-based learning (PBL) is an approach which intentionally focuses on developing these learning habits. It is a long-term process, which involves helping pupils reflect on and make progress with their learning habits as they work through each new project. Its purpose is not simply to produce project outcomes, but to develop independent life-long learners.

It is therefore best to view projects as vehicles for developing learning habits. These learning habits form the basis for planning any project. They are not the only consideration, of course. The first article in this series highlighted several elements that comprise successful PBL, and each of these elements will require planning for – but how?

Where to start?

Firstly, it is important to try not to look at each project as a discrete learning experience. Of course, there needs to be a range of projects to give learners access to a diverse curriculum; however, they should be seen as part of a continuum, with each new project building on the previous one. For example, a pupil who has learnt how to speak in front of an audience in one project may, in the subsequent project need to learn how to lead a small group.

Projects must aim to build on prior learning and enable pupils to practise new skills in a range of situations. Like many aspects of planning for PBL, this is very similar to longer-term planning in other curriculum areas.

In my opinion, the starting point for all effective lesson planning should be to look at who will be involved in the learning, considering what their current situations are like and what they need to do next in order to develop into well rounded lifelong learners. This could mean that learners in the same class may, on some occasions, experience very similar projects, whereas at other times, the projects could be very different, depending on individual learners’ needs. It’s worth mentioning that there is no such thing as a perfect project, as all teachers are well aware that things which work with one class may not work with another.

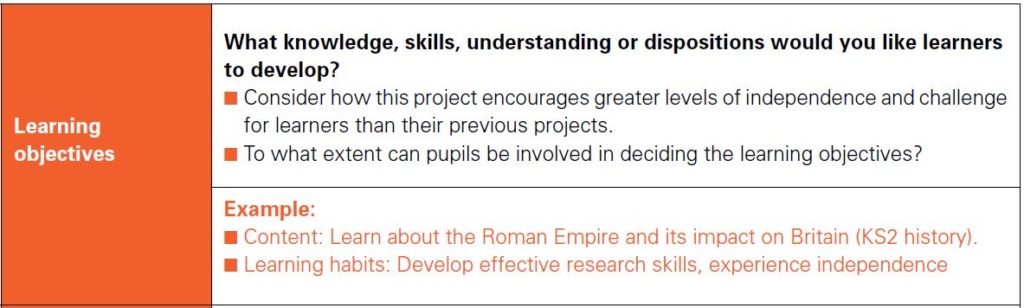

Pinning down the objectives

By taking into account who is going to be involved in the learning, you will be able to determine the objectives for the project. These need to pinpoint what you hope the pupils are going to achieve. It is important to be clear about this from the start, as the objectives are the foundations for all further ideas and plans.

Again, keep in mind that there is no perfect way to design projects; it is inevitable that different contexts will allow for different degrees of freedom over the objectives and ensuing plans. You may well have different types of objectives – some more focused on content, others more focused on learning habits.

In my experience, it is wise to limit the number of objectives so that you have the chance to explore them thoroughly. If you approach PBL with a long-term view of planning, you will be able to select the most appropriate objectives at the most appropriate time, whilst keeping a record of other key learning aims which you can incorporate in the future. This again reminds us that PBL is a long-term process about changing people’s learning habits gradually.

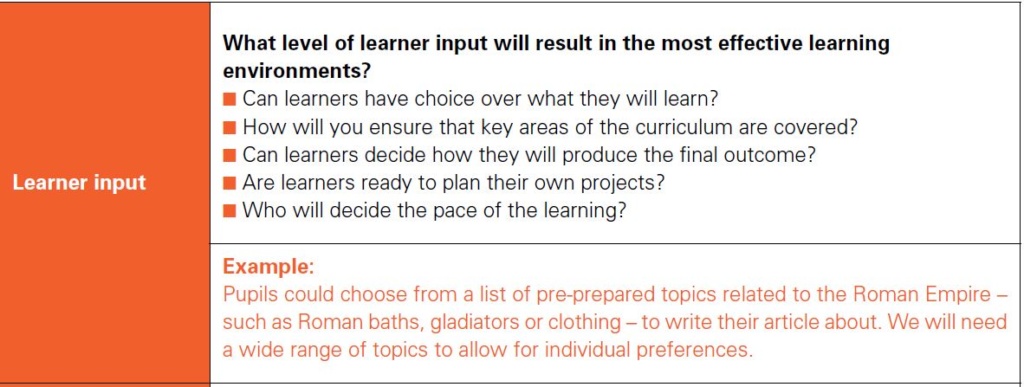

In addition, trying to engage the pupils themselves in deciding the objectives for their future learning can be a powerful experience. The most effective PBL is co-constructed, with the learner and teacher engaged in a two-way discussion as they design and carry out each new project. Pupils’ should have the autonomy to drive the whole process wherever this is feasible – as they become more reflective learners with growth mindsets, they will be the people best placed to determine which learning habits they need to focus upon next.

The level of freedom also has a big impact on motivation – the more pupils can be involved in deciding the project outcomes and how to achieve them, the more they will engage in the learning.

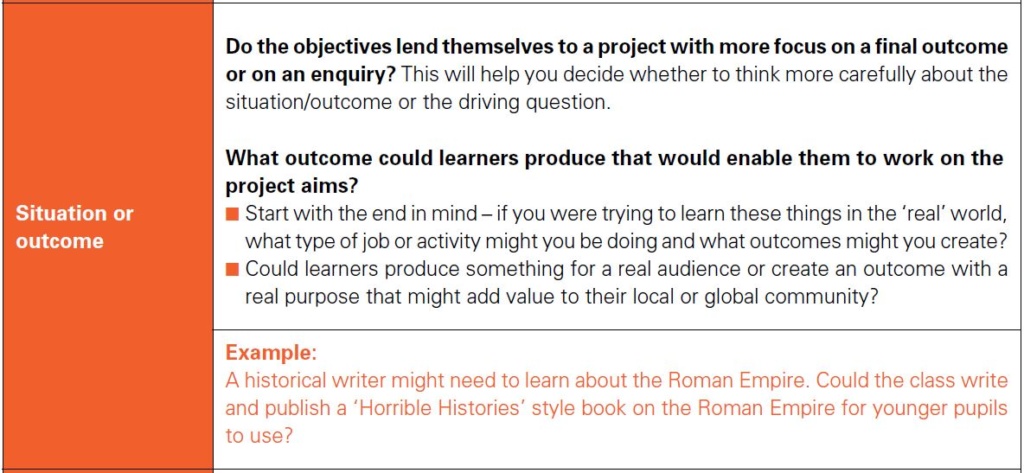

Establishing the desired outcome

After having determined the objectives, you need to think carefully about the outcomes. Start by thinking who might need to work on similar objectives in their real lives and what this would entail.

This is the fun part that allows you to come up with a wide range of different ideas – the crazier the better! The hard part of this process is narrowing the ideas to work within the limits of your objectives. It is at this point that it’s easy to get carried away with ideas you’ve generated, forgetting what objectives you set; like when a new trainee starts planning a lesson based around a fun activity instead of a purposeful learning objective. The key is to persevere with pruning your ideas down into a project that’s as real as possible, so it’s inspiring for learners, and allows pupils to work towards the key objectives.

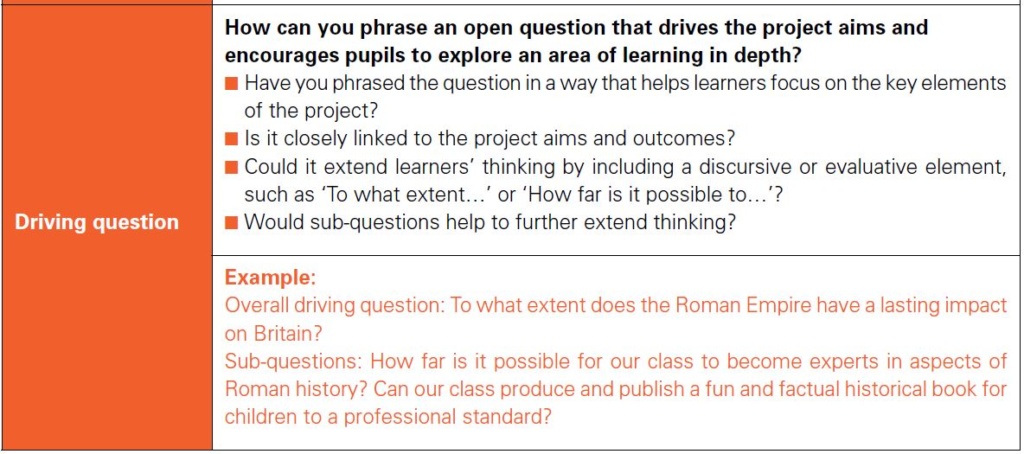

I believe that the majority of projects involve two main aspects, the enquiry and the outcome. These are interlinked throughout each project. If a project is more focused on enquiry, then a significant chunk of time may be spent on research and discovery, such as through interviews with experts or field study trips. In this case, the final outcome could be decided mid-way through the project and a driving question may be more significant. The driving question – a ‘big’ question that provides the stimulus for the project – will need to be crafted carefully, so it is open enough to give pupils scope to explore an area of learning in depth. The phrasing will also be important, so it may be useful to include a discursive or evaluative element, such as ‘to what extent…’ or ‘how far is it possible to…’.

On the other hand, if a project focuses on creating the outcomes from the beginning, the driving question may be less significant. In addition, research will be more closed and specifically related to how to arrive at the desired final product.

Once decided, the main objectives and outcomes form the foundations of your project. From here, the planning often becomes easier, as it can seem obvious which steps are the best to take next.

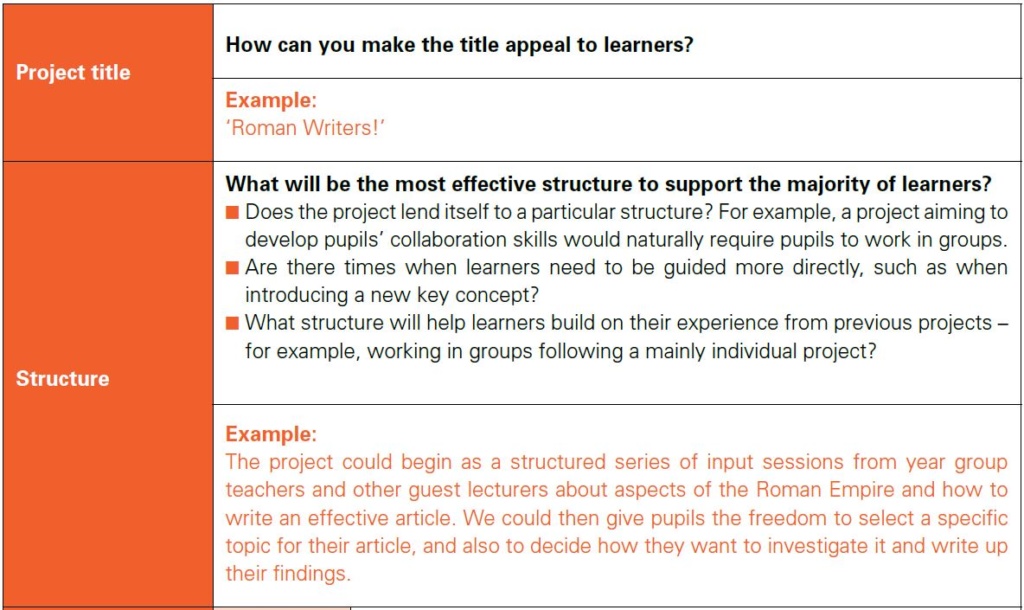

It is also likely that the most logical structure of the project will become apparent. For example, a project with an outcome related to developing collaboration skills will inevitably become a group or whole-class project. Conversely, if a key objective is for learners to become more curious about something in which they’re interested, the structure will probably involve individuals working on their own tasks at their own pace.

Ensuring accountability

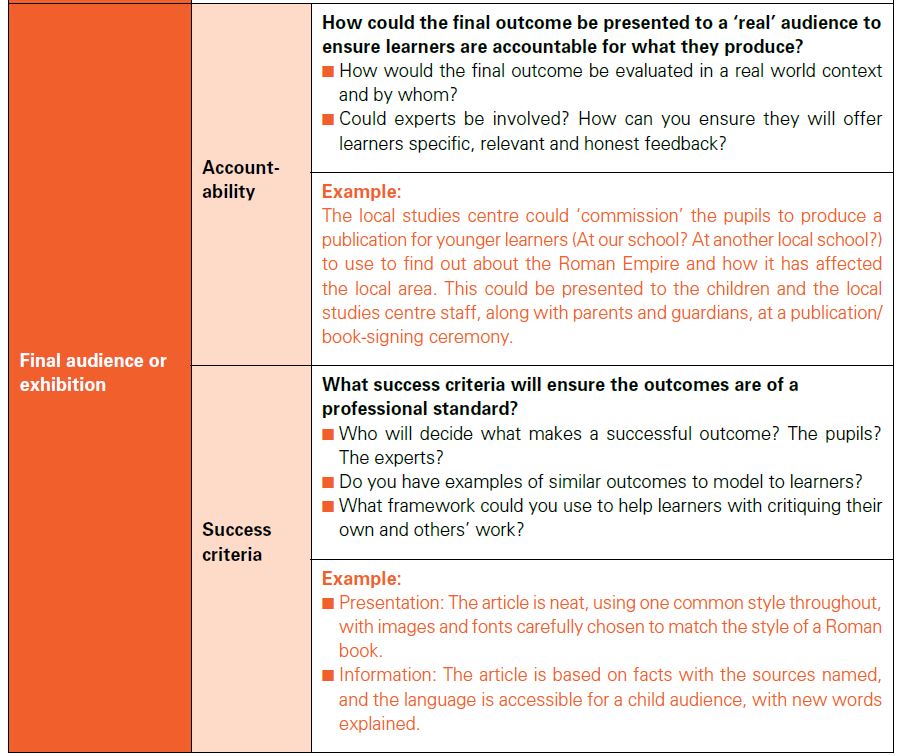

It is worth forming an idea of the format of the final exhibition early on. This is a very important part of all projects because it represents one of the main ways in which pupils’ learning will be judged. It is a way to hold learners accountable for their outcomes, in the same way they would be accountable in the real world.

For many pupils, the chance to showcase their learning will also be a celebration of the progress they have made in their learning habits and the quality of the project outcomes. For those pupils who have not put their full effort into the project, however, the final exhibition will come as a bit of a shock. They will realise that they have not sufficiently developed the required learning habits and have therefore produced a low quality outcome that does not represent their best efforts; such a realisation may motivate them to change their approach to the next project.

In order to hold pupils accountable for producing quality learning outcomes, the audience for the final exhibition should be carefully chosen to include people who are able to provide specific and detailed feedback on the outcomes. Ideally, you will be able to source genuine experts who may then also agree to be involved in other aspects of the project.

For example, both the Manchester and Lancashire Family History Society and Rochdale Touchstones Local Studies Centre have helped learners at Matthew Moss High School with various aspects of researching and developing their own family tree. This included supporting learners with researching archives at local libraries, visiting classrooms to assist pupils using genealogy websites and judging the final family trees as part of the final exhibition of learning. All these experts helped learners to see just how much is involved in producing an outcome to a professional standard.

Feedback and differentiation

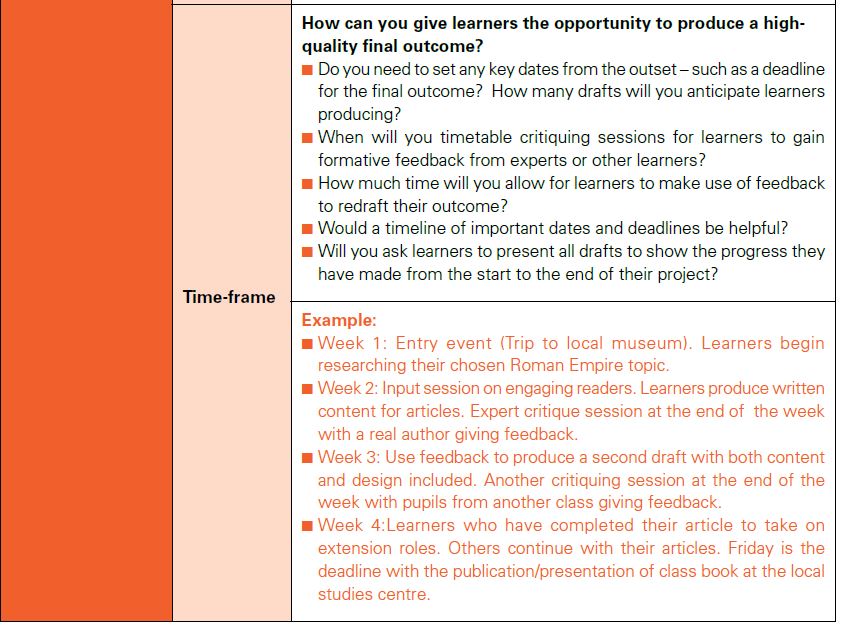

Once the final exhibition is decided, it will be easier to work backwards, planning out key milestones in the project to give learners the best possible chance to achieve quality project outcomes. You will need to allow time for at least one mock exhibition, where pupils have the opportunity to gain feedback from other people on their outcomes before the real exhibition. Following this, time must be dedicated for learners to make use of feedback in order to improve their outcomes – in my experience, pupils always need more time than you expect!

A subsequent article in this series will look in more detail at the drafting and critique process; however, it is worth noting that for critiquing to be effective, all learners need to have an understanding of what a quality final product will look like. As a result, it is helpful to make time at an appropriate point, perhaps as pupils begin to work on their final outcomes, for learners to create success criteria for their project outcomes. This could involve a class discussion with the help of experts and include evaluation of models or examples of real outcomes of various standards.

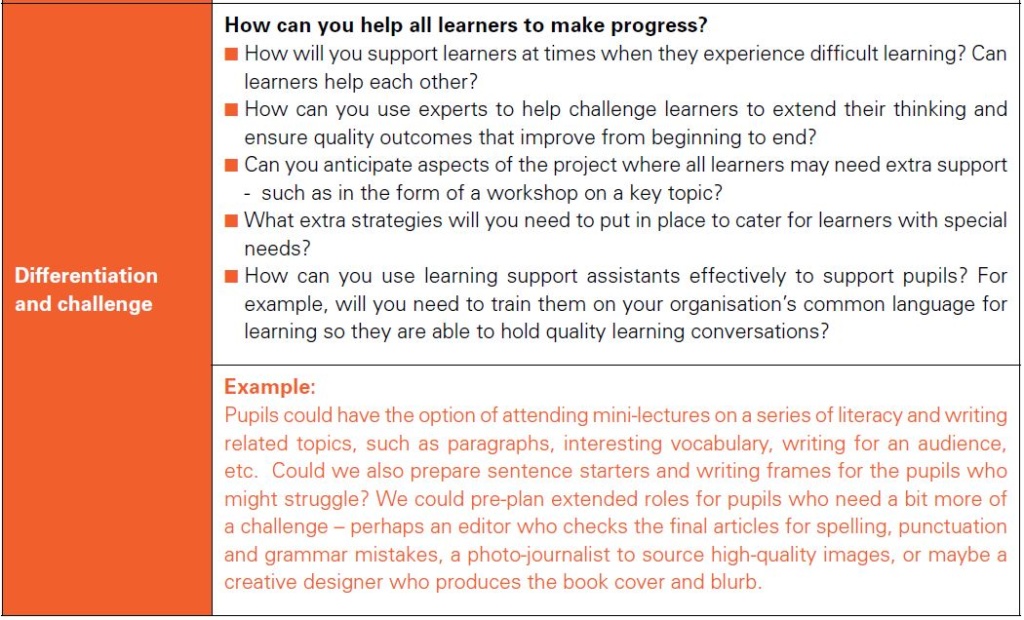

Success criteria help to set a professional standard to which all learners should aim. Differentiation will inevitably occur through the variation in the quality of the outcomes and, in the same way as a ‘traditional’ lesson, individual pupils need to be challenged to an appropriate level. All pupils will need specific support at different points along the project.

One way to differentiate in PBL is by providing input sessions for breakaway groups who need help with specific things, such as how to research effectively using an internet search engine or how to create a step-by-step plan of action. In some cases, you may decide that a whole class requires an input session which can be structured into the project. In other cases, it may just be one or two individuals who need to sit down with either you or a learning support assistant (such as if they need to access a piece of more complex text).

The nature of PBL being learner-led means that you will be able to dedicate time to individuals while the other learners in a class can continue with their projects.

In PBL, there will be some things that you can anticipate and therefore plan differentiation and challenge for in advance. However, because of the nature of projects, there will be occasions when you need to think on your feet and work with learners there and then to support their needs. For me, good differentiation is most effective when it is ‘just in time’ not ‘just in case’. The beauty of PBL is that opportunities frequently arise which you can draw on to challenge and support learners at the point when they most need it; and because this learning will be useful to the pupils, the learning experience will be much richer.

Reflection – central to a successful project

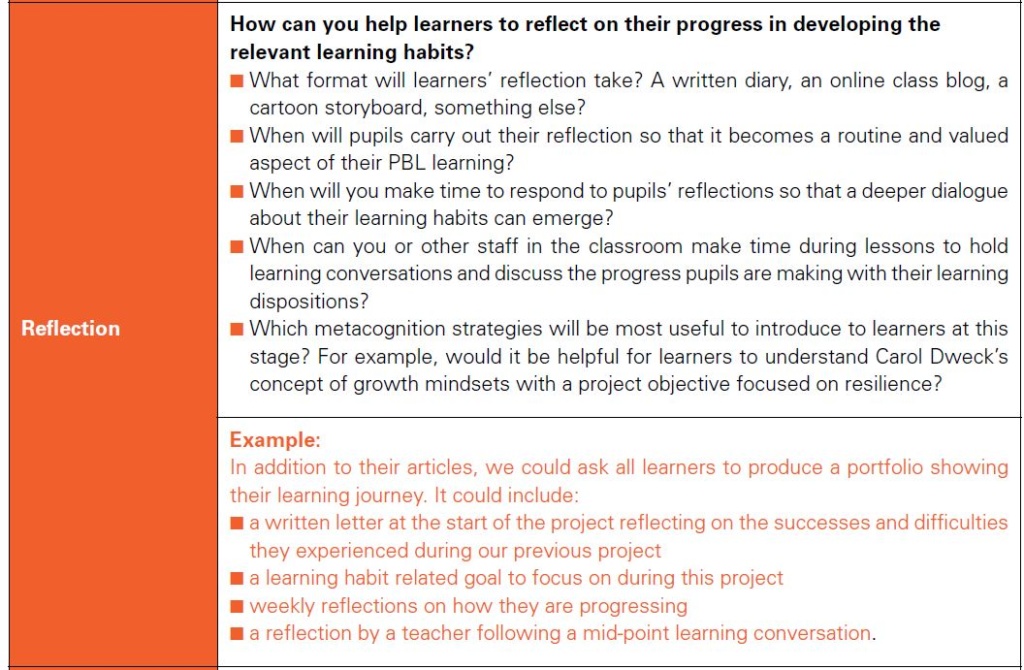

Finally, in my opinion, the most important aspect of PBL is also the easiest to forget –the incorporation of reflection and learning conversations.

When planning and carrying out a project, it is essential to keep returning to the purpose of PBL: to develop learning habits through pupils engaged in real situations. Teachers must put time and effort into helping pupils to reflect on the progress they are making with their learning habits.

It is easy to get caught up in the projects and their outcomes, and forget about the reflection. However, I believe it is reflection that distinguishes PBL from a simple sequence of lessons in any subject. Several well-known meta-studies have highlighted just how big an impact metacognition and reflection can have on learners’ progress. Therefore distinct time should be allocated to these aspects of PBL.

Within a project, learners should have time to reflect regularly, such as by writing a diary each week or adding to a class blog. These reflective narratives will be most effective if teachers respond to the comments and engage learners in a dialogue about their learning habits. Teaching staff will then be able to build on pupils’ most recent reflection by speaking with them about the relevant learning habits at an appropriate moment in the lesson, when it is ‘just in time’. For example, if a pupil’s written reflection focuses on resilience, the teacher can seize the opportunity within a lesson when the pupil is about to give up on something and speak with them about strategies to persevere with the task.

This highlights the importance of teachers ensuring they can dedicate a significant amount of their time during the lesson to engage pupils in these learning conversations. In this way, an effective facilitator of PBL needs to be well organised, and be able to foresee and respond to what pupils may need in subsequent lessons.

Underpinning effective learning conversations and reflection is pupils and staff who are involved in PBL all sharing a language for learning. There are several well-known examples such as Guy Claxton’s Learning to Learn and Ruth-Deakin Crick’s Effective Lifelong Learning Inventory. However, I don’t believe it matters which language you use to discuss learning, so long as everyone involved understands what each aspect means and can use it as the starting point for deeper conversations.

It is also useful to share other metacognitive theories with learners. At Matthew Moss High School, pupils are introduced to Carol Dweck’s growth mindsets and Transactional Analysis, which are regularly used to support conversations about the importance of effort and behaving in an adult ego state respectively.

Managing the practicalities

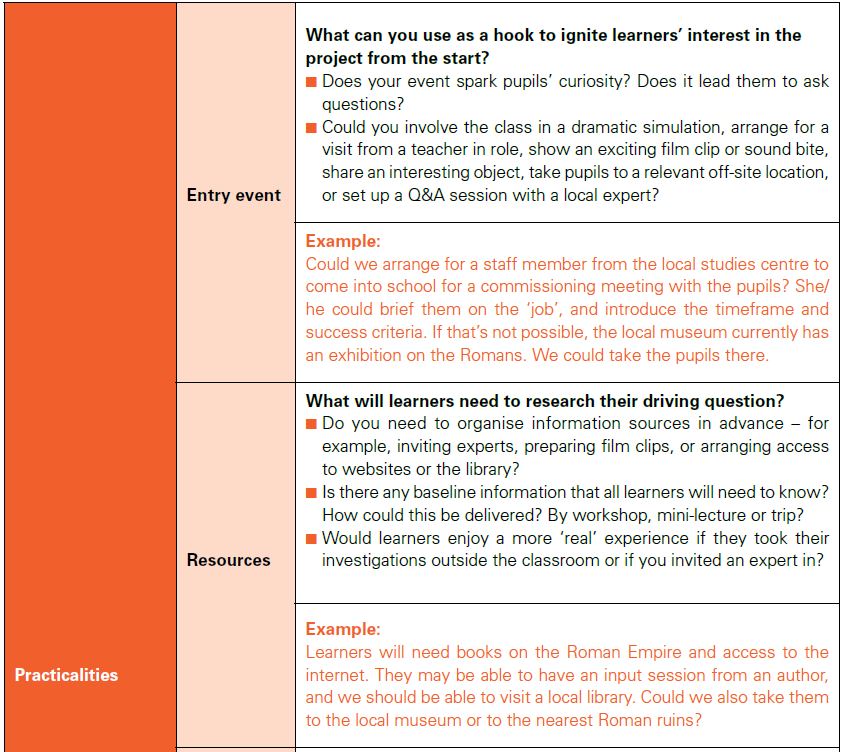

One of the last stages in the planning process involves considering all the practicalities. There will undoubtedly be many things to consider, yet if you anticipate as many of these in advance as possible, it will make it easier to manage once pupils are stuck into the project.

Key questions to ask yourself may include:

- How much structure will you give learners,

and at which points in the project? - How much input will you give your learners

in the project progression? How much of the

project will be teacher-directed? - What hook could you use to engage learners

in the project from the very start? - Do you need to find experts or plan trips?

- When do you need to start planning the final

exhibition? - Would it be helpful to create a brief calendar

outlining key milestones, such as when first

and second drafts will be critiqued? - What resources will you definitely need?

What resources do you anticipate that

learners might need? - When will you make time to respond to

learners’ reflections? - What will you do if some learners are

struggling to engage in a project?

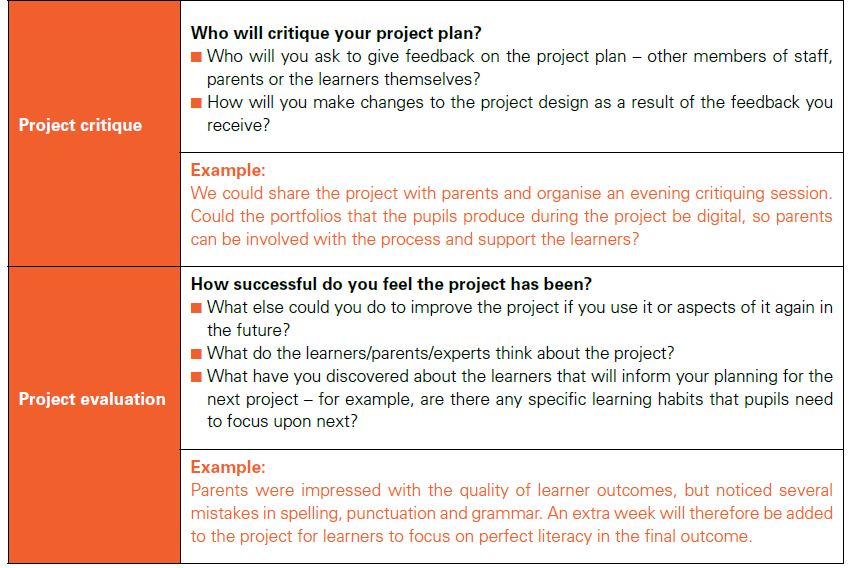

You will find a range of further questions to consider when designing your project in the example planning form at the end of this article. The notes included aim to indicate the thought-processes involved in each of the planning stages and highlight why particular decisions are made. This document is not meant to be followed to the letter, and can and should be adapted to better fit your own school’s needs.

Final steps

The last thing to do before you embark on the project is gain critique from other people. This could be the learners themselves, other staff or relevant experts associated with the project topic. This is a very helpful part of the process as there will inevitably be things that you have not considered and ideas from others which could help to make the project an even more effective learning experience. Ensure that you are prepared for some critical feedback, and are open enough to take this on board and make appropriate changes to the design of the project.

Finally, while there is a lot to think about when planning a PBL experience, you can be certain that things will not always take the direction that you anticipate. This is the exciting part of PBL which is what makes it so engaging for learners and staff. I do believe that planning carefully will make things easier as the project progresses, but at a certain point you just need to jump in and go with the flow!

Alexis Shea is a freelance education consultant, specialising in pedagogic approaches that develop life-long learners. Previously, she was a teacher and Head of Project-Based Learning at Matthew Moss High School in Rochester.

Knowledge trails

1. PBL for beginners – Alyson Boustead details her school’s

ambitious venture into project-based learning, and the

astounding impact it had on her learners’ creativity,

resourcefulness and resilience. Includes a selection of

helpful PBL planning sheets.

http://library.teachingtimes.com/articles/pbl-for-beginners

2. The best of PBL online – Join the PBL revolution with this

selection of websites and online resources to support the

design, management and implementation of your project

from start to finish.

http://library.teachingtimes.com/articles/the-best-of-pbl-online

PBL planning guidelines

This document gives cues to help when designing projects. It is not meant to be a prescriptive document, but to act as a reminder when planning. It can and should be adapted by teachers to make it relevant and purposeful to their own situation.