“Don’t raise your voice, improve your argument.”

[Address at the Nelson Mandela Foundation in Houghton, Johannesburg, South Africa, 23 November 2004]”― Desmond Tutu

In Talking about Oracy, the ability to conduct a debate can be likened to the ability to conduct an orchestra. The unification of various instruments, playing at different volumes, with different tones and sounds, needs to be considered and supported so that the outcome is more classical music than chaos.

The important thing to recognise is that volume is a good thing; the ability to hear an intellectual dialogue taking place in the classroom is one of the most rewarding ‘kodak moment’ that a teacher can experience. By laying clear expectations and a collective understanding of what is required, dialogue and debate can be nurtured and evolved in all settings.

The best place to start with any form of debate, is to first focus on the listening skills. We’re all guilty of participating in a dialogue, but not really being present for the content. In order to truly be involved, we must remember that the listening is just as important as the speaking.

A key support to reinforce the automaticity of listening skills would be to address the concept of debate in its key components:

- Listening to others and responding accordingly.

- Speaking clearly and audibly ensure comprehension.

- Justification of ideas through reasoned development.

Encourage the ability to define a debate

When we consider the significance of listening, this is particularly important when students begin to recognise that effective debates need to include an active dialogue. This needs to be developed and formulated through research, prepared, but also reactive responses that have been formulated based on the information provided. Debate needs to be appreciated as fluid and interchangeable, as opposed to stagnant and clear cut. By learning how to listen and adapt, this allows students to gain an integral life skill that they will need to utilise in later life.

Lay out clear rules and expectations that will support and encourage participation of all.

In order to support the development of a suitable climate for debate, providing bespoke and prepared topic points can often be instrumental in laying the foundations of communication. The more confident a student feels about the subject that is being discussed, the more likely they are to contribute in some form. However, once this confidence is developed, it is important to expose students to a variety of topics and focus points. T

he desire to venture down the avenue of engagement can actually have a detrimental effect on learners as it hinders their exposure to topics through fear, they may be foreign or negatively received.

As debate may cover particularly sensitive subjects, it is vital that students are provided with an understanding of acceptance and tolerance. By considering different opinions or thoughts, this will allow students to approach these sessions in a manner that promotes equality, and respect from all participants.

Preparation is key!

This is the element of debating that turns a rant into an argument; where chaos becomes control, and interpretations can be justified.

The ability to prepare for a debate is integral to success. In the same way, the skill of preparation and planning can then be transferred into all subjects and all situations where someone is either required to provide an extended written or oral response.

To provide outside contextualisation, various jobs are now requesting potential applicants to provide a short presentation on a particular topic. Others, particularly those participating in managerial interviews, are requested to complete a written task that gauges their ability to articulate their competence. The ability to prepare and plan ahead is crucial to success. Although we can often be partial to the temptation to ‘wing it’, more often than not, these situations lead to less clarity, less comprehension, and less of a high calibre response as opposed to a calm and collected counterpart who has prepared and is ready for whatever may come their way.

In order to help to prepare effectively for a debate, there are four key focus points that one should consider:

1) What are the initial interpretations of the statement or topic point?

In order to commence planning and preparing for their address, the first task is to develop a reasonable viewpoint or approach with which to fundamentally base their ideas and evidence on. This element is the ‘what’; the tip of the iceberg; the ‘big idea’ or the opening statement on which all of the work will be based. The construction of this standpoint can be strategically centred around four clear consideration points:

- Reasoning

- Impact

- Evidence

- Alternatives

By first recognising and gaining a basic overview of each of these four areas, this can allow participants to formulate a reasoned discussion through developing each point. Whether this is done independently or collaboratively, deeper questioning skills can consequently be adopted in these circumstances in order to ensure that critical thinking is accessible.

2. How is the response to be structured?

The structure for a debate is relatively similar to that of a speech, therefore students can utilise the same skills in both forms of communication, thus supporting their exposure and capacity for mastery.

When we consider how students are taught to compose a speech, there are a plethora of structures that can be taught in order to scaffold. It would be illogical to just provide one structure and claim that it is the ultimate technique, as in essence that would completely go against the emphasis that all strategies and techniques are to be considered based on each individual establishment’s context. Two possibilities to consider would be:

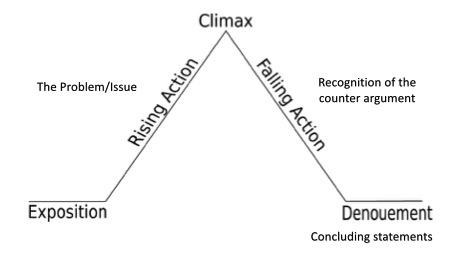

The Freytag Pyramid

In the nineteenth century, Gustave Freytag, a critic of Greek and Shakespearean drama, came up with a five-act dramatic structure in order to explain effective content.

In the same way, it could be possible to transfer this understanding into a supportive structure with which to develop the capabilities of your students to present a well-crafted and purposeful speech/debate.

- Section 1- The Exposition

- What is the main focus going to be?

- What factual statements are you going to present to the audience?

- Can you entice their interest by setting the scene?

- Section 2- The Problem/Issue

- Why have you chosen this stance?

- What factual and statistical evidence do you have to support your interpretations?

- Section 3- The climax

- What are the impacts of your proposal?

- Why is your motion the most logical choice?

- How will your motion be positive for the audience or society?

- Section 4- Recognising the counter argument

- What alternative suggestions could be made?

- What might someone who objects to your motion say?

- Why is your motion the most rational and obvious choice?

- Section 5- Concluding statements

- Reiterate your main standpoint.

- Reinforce your motion and provide a thought-provoking/emotive closing statement.

Another approach is a more simplistic portrayal of the deeper questioning strategy that was approached in the development of questions (the What? How? Why? approach). By allowing students to first consider the ‘big picture’, this consequently paves the way for students to develop their ideas in more intrinsic detail.

| The ‘Big Picture’ | What is our main standpoint on the subject? What is the key message that we are attempting to get across to our audience? If this was a piece of critical thinking, what would be our thesis statement (the umbrella that links to all of our ideas) |

| A Convincing argument | What is our ‘hook’ to gauge the reader’s attention? |

| Surface level ideas and understanding | What examples can we use to support a piece of writing? Can we link our ideas to anything in the news or everyday life in order to make it relatable? |

Although a reduced version of the other two techniques, what this approach allows for is a less prescriptive response. Accessible to all subjects that require extended writing responses, the recognition of a three-tiered approach is one that could easily be adopted in a whole-school strategy.

3. Can you show a recognition of alternatives?

When considering the alternatives available, one must first consider whether the motion put forward is authoritarian or libertarian.

- Authoritarian

- The authoritarian approach is one of strict obedience to rules and regulations that have been introduced and implemented by an autocratic government.

- When considering your motion, it is advisable to consider whether and to what extent you are petitioning for actual change. Although the concept of an authoritarian approach should obviously be discouraged, it should still be recognised that the concept of providing a solution to any problems is integral to a logical debate. The ability to provide these solutions can also be deemed as a beneficial life skill!

- Libertarian

- A libertarian approach would be one that doesn’t advocate any motions or proposals that would jeopardise the process and concept of free will.

- The ability to consider this approach is the ability to question whether there are any elements of the Human Rights Act that may be infringed through its implementation. These can include freedom of speech, expression, movement or trade, etc.

Once this is considered, it is then beneficial to explain to students that the key to an effective opening argument is the ability to address and provide a counter to questions that will commonly be asked by other students. These reasonings include:

- Are there issues with the proposal going against the general consensus of the area (does it impede with any cultural, political or social issues)?

- What are the alternative options? Why is this motion the most important one moving forward?

- Is this issue one that should be a stand-alone topic or could it actually be approached as part of a wider development?

- Are there any negative implications or is there any detrimental impact upon its development?

- What are the financial stresses that are involved? Where will this money come from and is it financially viable? Is there a long-term cost involved?

- Who will be accountable for the development of the motion and its implementation?

4. Have you considered the rebuttal?

The opportunity to provide a rebuttal is the fundamental aspect of speeches becoming a debate. By initially allowing students the time and opportunity to prepare and acknowledge questions that could be asked of them, this will therefore provide them with the encouragement and confidence to partake in communication instead of becoming disengaged or disconnected with the process.

Although this should be encouraged to become a more active dialogue, it may be beneficial to provide all students with a crib-sheet of questions for them to engage with including:

- Why is this so important now?

- How does this impact on society?

- Who is affected by the issues?

- Who is affected by the resolution you are suggesting?

- Are there any societal impacts that need to be considered?

- Why is this better than the alternative?

If presented to all during the preparation stage, students can prepare their responses without a fear of whether they will feel interrogated. If students can then keep these support sheets or resources, we can then begin to form two-way (albeit initially scripted) dialogues.

They can also be used to gauge audience listening skills, with the implementation of shorthand note-taking to allow the listeners to consider which questions have been covered thoroughly, and which questions would be best to be asked in order to gain greater depth of comprehension.

Consequently, students need to be encouraged to participate in the art of debate at all stages of their academic journey. The concept of being able to participate in a conversation that may elicit a particularly strong emotional response without being perceived negatively is integral to effective communication within society.

Sarah Davies is a lead practitioner and head of English in a multi academy trust secondary school. She is also a lead examiner for a national exam board. Her book, Talking about Oracy: Developing communication beyond the classroom, published by John Catt Educational, is out now, price (£14) for more information click here..

Register for free

No Credit Card required

- Register for free

- Free TeachingTimes Report every month