I have spent years trying to help teachers focus on learning, and in this endeavour have found that one of the biggest ‘space invaders’ is teaching. Phrases such as ‘teaching and learning policies’ or ‘teaching and learning strategies’ have been used more and more. But close examination suggests that they might better read ‘teaching and teaching’, since the real attention given to learning is minimal.

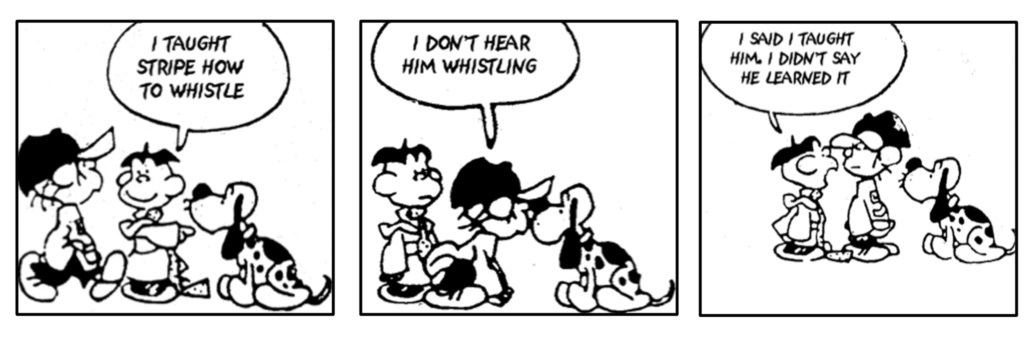

But I have also found that teachers laugh freely at this Bud Blake cartoon (1974 from the ‘Tiger’ series):

Something my wife Patsy said about her horse-riding instruction led to some rich thoughts on this theme. Before writing about it I checked the existing literature. On the internet how many results when you do a search for the title of this article (as a complete phrase, i.e. in inverted commas)?: ZERO! The results go up when you search for the answer ‘when teaching leads to learning’: ONE!

So what is it that Patsy said? When being instructed, one’s attention is given over to making sense of what the instructor is talking about, and you lose the focus on making sense of what you’re doing. This made us think about whose narrative is driving the process.

Human beings are narrative beings: all human experience is understood through stories and enacted through stories. The human animal is the only one with language, and it has developed seven thousand languages around the world. The way s/he uses language, internally and externally, develops everything from consciousness to culture—and conflict. The basic structure in use of language is the ‘story’—subject verb object, and this narration can carry on to high complexity.

Narration is ever-present:

- Silent narration = thinking

- Invented narration = imagination

- Physical narration = writing

- Number narration = counting

- Over-narration = worrying

Bruner used the phrase ‘life as narrative’ to indicate the view that we organize our experience of human happenings in the form of narrative. Story-telling is life-making: we are our stories: ‘a life as led is inseparable from a life as told’.1

The introduction to this article used the data which shows that the relation between teaching and learning has a thin narrative in our culture. And this relates to the fact that narratives about learning are rarely heard in classrooms. This stance helps us notice the main stories about learning (and teaching): 2

- learning = being taught (instruction)

- learning = individual sense-making (construction)

- learning = building knowledge as part of doing things with others (co-construction)

Patsy also has another riding instructor, who uses an approach more of the second style: when he gives an instruction, he follows it with ‘Why?’ and then a narrative which not only provides a rationale but also gives the learner a focus for their narrating to themselves in the action that follows.

So the answer to the question in the title is: Teaching leads to learning when the learner develops a new or more complex narrative on the topic. Complex is an important word: simply adding more ideas is not enough—they must be connected. How does that fit with your experience—of your own learning and of others? And what are the implications for classroom practice?

Teachers can help learners to build up greater understanding of how their learning works. Making learning an object of learning is supported through a process of plan–monitor–review, in other words through a meta-learning process. In this way students not only add language and add strategies, they also build the crucial conditional knowledge of how to monitor and review whether their learning is working. The combination of strategies together with meta-learning is what is needed.3

Teachers can promote learning about learning by using classroom activities which:

- make learning an object of attention

- make learning an object of conversation

- make learning an object of reflection

- make learning an object of learning

Last year a deputy head contacted me under the subject line ‘Notice, narrate navigate’. I thought ‘Wow that’s a powerful understanding!’, and he went on to attribute it to me.4 His work started with ‘My initial consultations led me to think that the children were rarely strategic or deliberate about their learning. They appeared not to know themselves as learners and were unaware of their potential to be in control of their own learning.’ From there he developed learning stories, individual storyboards and whole-class navigation posters.5

He concluded: ‘The more someone notices their learning, the more they are able to narrate their learning. The more richly someone narrates their learning, the more they see their own role in it. The more someone sees their own role in their learning, the more they become able to plan, monitor and review (i.e. navigators of their own learning)”.6

When I was first a maths teacher in a sixteen-form-entry comprehensive school, the school had adopted an ‘individualised teaching programme’ (i.e. individualised worksheets). In every session, I gave time to the directive: ‘in twos and threes tell each other what you’ve noticed about the maths today’. Wow—so reflective and self-regulating! I’m still in touch with some of them nearly forty years later.

I was talking with four 10-year-old students in a school in an underprivileged part of Sheffield about their experiences of learning in classrooms when one of them said that they ‘distill’ their lessons. After asking them for some explanation, I asked whether they could distil our conversation so far. ‘Yes’, they said, and, as they turned to discuss it in pairs, I heard one use the word, meta-learning. When the paired conversation ended I enquired: ‘Did I hear you use the word meta-learning?’; ‘Yes’; ‘What’s that? Metal-earning?’; ‘Nothing to do with metal’; ‘Knowing yourself as a learner—which is a good thing’ (see video clip 8 on my website).

With such strategies we might be able to achieve the goal indicated in this image:

Let’s make teaching reflect learning.

Chris Watkins is an independent consultant and project leader. His publications are available at www.chriswatkins.net

References

- Bruner, J.S. (1987). Life as narrative. Social Research, 54 (1) 11-32, p. 31.

- Wagner, P., & Watkins, C. (2005). Narrative work in schools. In A. Vetere & E. Dowling (Eds.), Narrative therapies with children and their families: A practitioners’ guide to concepts and approaches (pp. 239-253). Hove: Routledge.

- Watkins, C. (2001). Learning about learning enhances performance. London: Institute of Education School Improvement Network (Research Matters series No 13).

- Watkins, C. (2015). Metalearning in classrooms. In D. Scott & E. Hargreaves (Eds.), SAGE Handbook of Learning (pp. 321-330). London: Sage.

- Emmett, S. & Lightfoot, S. (2018), Notice, narrate, navigate: Developing a framework for reflection on learning. Chapter 10 in Frost D., Ball S., Hill V. and Lightfoot S. (Eds). Teachers as agents of change: A masters programme designed, led and taught by teachers. Letchworth Garden City, Hertfordshire: HertsCam Publications.

- Adapted from: Watkins, C. (2010). Learning storyboards (presentation slides). Available at: www.chriswatkins.net/presentations (slide 23).

Register for free

No Credit Card required

- Register for free

- Free TeachingTimes Report every month