Energy Coast UTC opened in September 2014, but by the end of the first year the headteacher, the deputy head and the business manager had all resigned.

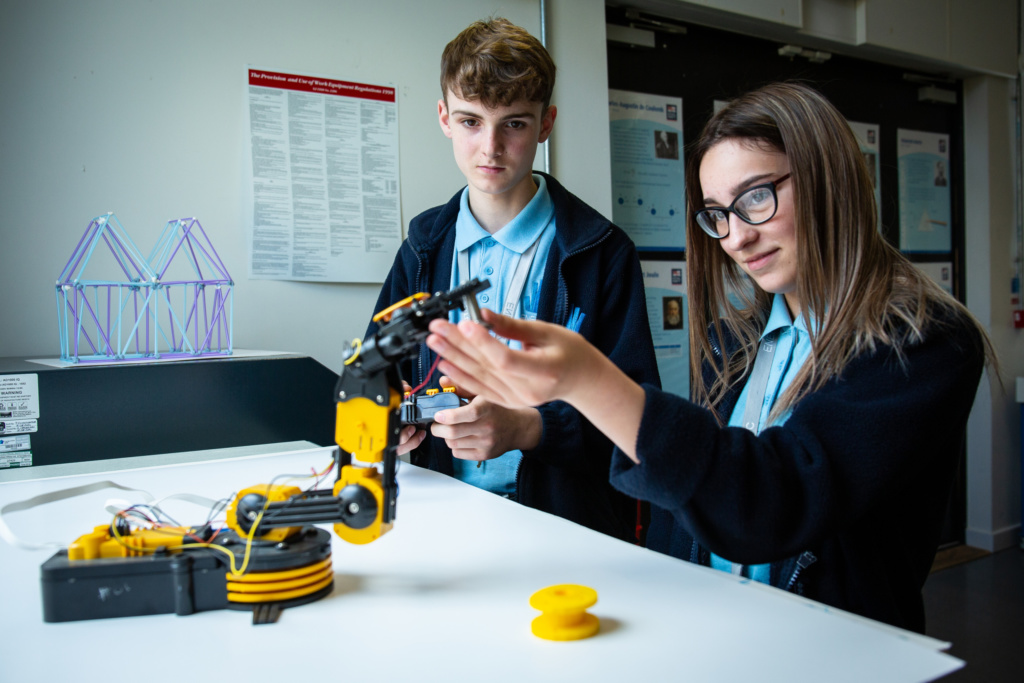

University Technical Colleges are a new style of school, quite unlike the comprehensives and academies most people are familiar with. They are career-focussed schools for 14–19 year olds where students work toward vocational qualifications and gain hands-on experience in local companies, alongside GCSEs or A levels.

There has been a slower take up of places in UTCs than anticipated. Some have run into debt and eight have closed, so it is a programme which has more than its fair share of challenges.

I had worked in many schools and was accustomed to turning things around. I could see there was the potential to raise standards at Energy Coast UTC and make it an Ofsted ‘Outstanding’ school, despite exceptionally poor exam results and an unfortunate start.

I was keen to take on another headship role after working for the Association of School and College Leaders, but knew I did not want to work in a traditional mainstream school doing EBacc. I felt this approach was not suited to the needs of many of the children I had worked with.

I didn’t become a teacher until I was in my 30s. I started off working in histopathology in Leeds, but after I had my four children I became fascinated by the learning process and how quickly children absorb knowledge and ideas, and so I decided to train as a science teacher. I have always taken an interest in the opportunities schools can offer to children who are not natural academic high fliers.

For much of my career I have been in challenging settings in the white coastal areas and big industrial towns of the north, which both have high levels of social and economic deprivation. Because of my experience, Energy Coast in Workington in West Cumbria interested me. The area is geographically remote and has very settled communities, but around 40 percent of the children are entitled to free school meals.

Having worked in Lancashire for many years, I was also keenly aware of the attractions and the quality of life in Cumbria. While the UTC is in the middle of an industrial estate, just 20 minutes from my office I can be fell walking or enjoying wild swimming in the Lakes.

Taking Up The Reins

While I was well aware that there would be an uphill struggle, looking back I was possibly a little too sanguine. In my first few weeks I discovered serious financial irregularities and soon after my arrival the school was served with a financial notice to improve.

In fact, in the first half term it seemed that every time I lifted up a stone, it revealed a major problem that had to be dealt with immediately. In October alone, the DFE and the ESFA came into the school; we were audited; the Board of Governors was restructured; and we got a new Chair of Governors, plus new industry representatives recommended by the University of Cumbria.

There were other issues: UTCs generally have specialist facilities for engineering or science. However, Energy Coast was using state-of-the-art facilities in an adjacent building that did not belong to the school. It had been developed to train apprentices, but while the facilities were first-rate, the costs were exorbitant.

I was also aware that some students had narrow horizons. Partly this is because they have some excellent opportunities for employment with Sellafield, a major nuclear energy processing plant, right on their doorstep, but I knew part of my role would be about raising aspirations and encouraging young people to look further afield.

For the first year I worked from seven in the morning until ten at night and usually at least one day at weekends. There was so much to do! In addition to the financial issues, the exam results were shocking, both at GCSE and A-level. Students were at least two grades below where they should have been, but this was not surprising as basic procedures were not in place. There were no targets for students, no monitoring of the quality of teaching and learning. The staff structure was ad hoc, to say the least, and pay was not related to responsibility or accountability.

Improving Teaching And Learning

Educational standards are paramount so I watched everybody teach and then identified some excellent young members of staff and recruited them to the new Senior Leadership Team.

We set strict guidelines and told teachers: ‘This is what is going to happen in every class. There will be an objective for every lesson, differentiation, active learning and we will involve employers in classes too’. We instigated a full CPD programme for all staff, alongside monitoring and mentoring, with staff working in teams of two and three. A few staff weren’t happy and some left, but now there is a tight quality assurance programme and many of our young staff have developed into truly outstanding teachers and leaders.

As the UTC is a small school, it is difficult to spot trends since we only have 70 or 80 young people in a year group. We use Cognitive Ability Tests at the beginning of Year 10 and we measure levels for English, maths and science so we have a basis to work from.

We can’t do Progress 8 (The UK government’s current measure of school performance) because we don’t do the subjects on the government lists—they are looking for progress over five years from Years 6 to 11. However, we can prove almost three grades’ progress in two years across all subjects: 3.5 in technical subjects and 3.0 in English. Forty per cent of all our pupils are disadvantaged and, while they don’t do quite as well as the rest of our students, they are still gaining more than two grades in two years.

All of our students do GCSEs: English language, English literature, maths, chemistry, biology, physics and one option, which might be geography, history, sport, ICT or business studies.

Unlike most mainstream schools, our curriculum includes regular lessons in employability and our students also do three engineering qualifications: level 2 Design Engineer Construct (DEC), a level 2 BTEC in Engineering and a level 2 practical apprenticeship diploma in Performing Engineering Operations (PEO). This might include preparing and using CNC lathes and milling machines, assembling pipework systems, preparing and using manual Oxy/fuel gas welding equipment, etc.

We were delighted by Ofsted’s comments in June 2019: ‘The school’s culture engenders in pupils very positive attitudes to learning. By the end of Year 11, pupils are literate and numerate. They have had first-rate careers guidance and many excellent opportunities to develop high-quality skills, which makes them very employable.’

Safeguarding

We recruited some excellent people from further education, some good staff from industry, including time-served welders and machinists, but in the early days, some of the vocational staff did not appreciate the difference between working in a school and working in industry. We found that external doors were left open, and on occasions a minority of staff left a group unattended, which was a serious health and safety issue. We set the basic safeguarding procedures in place very quickly. I have to say it took longer to embed them, but we are 100 per cent there now.

Social media is another issue. Our learners don’t just get a safeguarding talk from a teacher: they also get young apprentices coming in and talking to them. These are young people who are just a couple of years older than our students. We have had a project management apprentice and others from civil and electrical engineering. They are good role models and young people are more likely to respond to them than to teachers, so when they say, ‘I would lose my job if I put this on my Facebook page’, our students listen.

We made sure that young people were involved in developing behaviour policies. We took all the students in small groups into the hall for a session about reasonable expectations. We wanted them to be involved in setting codes of behaviour and reward systems. Then employers came in and talked about their expectations for behaviour in the workplace. Some students were quite shocked to find out how draconian their discipline measures can be, but obviously in the nuclear energy sector there isn’t much leeway for negotiation!

Industry Links

After a wobbly start, employers have started to engage with us more and we now have about a dozen companies advising us, providing extensive work experience and offering that employer perspective that our students need. They invest heavily in our young people. When students start in Year 10, they all work for an employer for at least an hour every week on a real project and the amount of time they spend in industry increases each year.

Morgan Sindall Infrastructure have stood by the UTC through thick and thin. They pay for every student’s uniform, which includes polo shirts, fleeces and safety boots. They also recently took a group for a week’s Outward Bound course. They are closely involved with the school and get to know the students well, so it is not surprising that their last cohort of degree-level apprentices all came from Energy Coast.

Employers also provide guidance on local skills shortages and vocational areas we could concentrate on. They may ask us to teach particular CADCAM packages, Autodesk and Health and safety modules so our students are trained in industry-standard skills.

Their presence has had an impact on the atmosphere at Energy Coast. Behaviour was poor when I joined, but now students know that they must behave as if they were at work. For example, when they meet somebody for the first time they need to look them in the eye and shake hands. Their behaviour around the college is now exemplary.

Employers are familiar faces in the school. One student told me: ‘I have just been for an interview with the man who was in the canteen with you last week’. They know if they are fooling around in the corridor an employer is likely to see them and that it could have a detrimental effect on their future employment. They are also aware that attendance and punctuality are important: 95 per cent is not high enough.

Measures of Success

We have made huge progress. A new Business Director has taken up post and we have some great new support staff.

The school now has 297 students from years 10 to 13 and recently we have started a group for gifted and talented learners from other schools. Now, 20 students come to us at the end of Year 8 for an intensive summer course where they study bridging units in STEM and then join our Year 10s in September. It is pressurised and hard work and they quickly learn that we have high expectations at Energy Coast. The school day is long—from 8:30 to 4 pm—with the option to stay until 5 pm for students who are ‘off track’ or who need extra sessions or to pick up different options.

In June 2019 we had our second Ofsted inspection and were rated ‘Outstanding’ in every area. I was delighted, but not surprised, by the inspectors’ comments on our students: ‘They develop a very clear understanding of how they can contribute to Britain’s engineering economy and integrate with a diverse community. Pupils leaving the UTC are exceptionally well prepared for the next stages in education, employment and training.’

I have found that a small minority of parents believe we are too harsh and point out that the children are not yet in the workplace. I have also heard that in the community we are seen as being very strict. This is fine by me, because 90 per cent of our young people leave Energy Coast UTC to take up apprenticeships. I believe that we want these positive outcomes for all children, including our own sons and daughters.

Cherry Tingle is principal of Energy Coast University Technical College. She was previously a science teacher, a secondary headteacher and Lead Officer for National Curriculum, Assessment and Data Policy at the Association of School and College Leaders.